My Life In Tech is telling the stories of Africans making a difference in the world of tech.

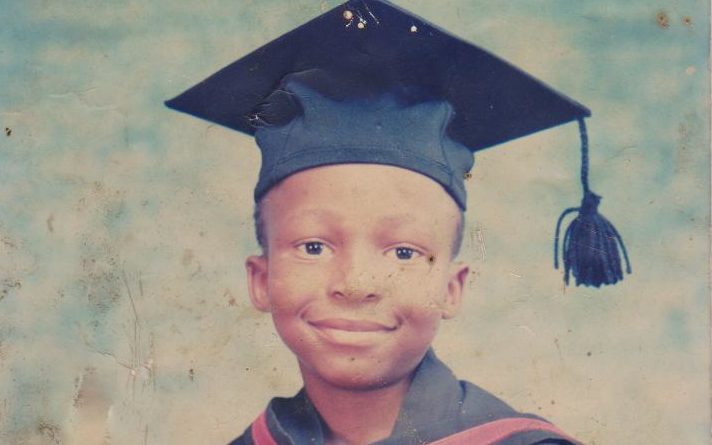

Before he turned ten, a typical Friday would find Vuyane Mhlomi on one of many trains making his way back home from school.

His journey typically did not end at home. He would only stop there to pick up a change of clothes for his father who was very often hospitalised due to his poorly controlled diabetes.

Coupled with his mother’s cardiac condition, Vuyane spent a lot of his time in hospital queues waiting for any one of his parents to be attended to.

He tells me that the doctors worked hard. There were just too many people who needed help and not many doctors wanted to move to Khayelitsha, his hometown, due to the high crime rate.

Today, Vuyane is a medical doctor, Rhodes scholar, and the co-founder of Quro Medical – a startup making it possible for patients to receive the best care from the comfort of their homes.

While the company was founded in 2018, the pandemic made a case for what they had always wanted to achieve – a way for doctors to care for their patients outside of the hospital.

“There is overwhelming scientific evidence that demonstrates that patients do better at home, but we have very hospi-centric healthcare systems that incentivise treatment in dedicated facilities,” he said during our Google Meet call.

From Khayelitsha to Oxford and back to Cape Town, his journey has been one of resilience and a desire to make healthcare accessible for everyone.

He is Dr Vuyane Mhlomi and this is his life in tech.

“Call my son, my son’s a doctor”

On the day he graduated from the University of Cape Town, Vuyane was all smiles. He had just finished in the top three of his class and he was standing on the steps outside UCT’s Jameson Hall granting an interview to the Cape Times.

In this interview he spoke of his mother, Nomsa.

“My mom has been my mother and my father. This belongs to her,” he said.

Vuyane lost his father when he was eleven years old. His mother was left to care for him, his three siblings, and a few cousins, on her own.

“I remember at one point, there were about ten of us in the household,” he told me.

The family relied on his mother’s disability checks and social grants to get by and of course to go to school.

“I mean, we didn’t grow up in squalor, my mum really did try to provide. But we were definitely poor.”

Growing up in Khayelitsha was tough and from a young age, Vuyane knew that education was the one way he could possibly move upward socially. This was how he fell in love with studying; it was the way to change things – his ticket out.

When the time came to choose a course to study, medicine was the winning choice.

While his decision was due, in part, to the many hours spent sitting and waiting for a doctor to attend to his parents, Vuyane remembers one event that solidified his decision.

It was in his last year of high school. On the night before his matric exams, his mother had a stroke that they were lucky enough to catch early. She had developed a clot in her heart from an undiagnosed cardiac complication from when she was a kid and that clot had dislodged and gone to her brain.

Thankfully, she was able to get access to therapy and this helped to dissolve the clot and limited further neurological damage.

“And that inspired me. It told me that when medicine works in the way that it’s supposed to work, there’s a real potential to save lives.”

There is something to be said about what happens when your loved ones buy into your dreams. In the middle of her stroke, with her speech slurred, Vuyane’s mother said to the doctors attending to her, “Call my son, my son’s a doctor. Call my son.”

He was in grade 12, he had only just applied to study medicine and was yet to even write his entrance examinations. But there she was, in a time when she did not need to think of anything else, speaking of his dreams as if they had already come to fruition.

On the day he walked across the stage to accept his medical degree, in her excitement she would tell the Cape Times, “I was sweating. I was sick. I was happy.”

The road to Rhodes and the birth of a businessman

After graduating from UCT, Vuyane could finally begin practicing as a doctor. He began his internship at Soweto’s Chrishani Baragwanath Academic Hospital.

In his second year there, he applied for the prestigious Rhodes scholarship to Oxford University.

“I was determined to do a PhD, so I reached out to a prospective supervisor – who did not return my calls.”

Not one to back down easily, Vuyane made calls to Oxford to ask why he was being ignored. His call would eventually get picked up by a professor who was intrigued by his tenacity. He got an interview and the rest they say is history.

In his Rhodes profile, Vuyane speaks of the opportunity and acknowledges what his being there meant.

“You can be a Rhodes Scholar even if you are from Khayelitsha.”

Vuyane would pursue a PhD in cardiology with his thesis centering around the interesting concept of how the hearts of pregnant women rapidly increase in size to accommodate the foetus but they increase in a way that should normally cause a heart to go into shock.

In many ways this reminds me of the work Quro Medical is doing today in the field of Remote Fetal Monitoring – allowing doctors to keep a close watch of a pregnant mother and her foetus while she remains in the comfort of her home.

Following his PhD, Vuyane began to figure out next steps.

“The PhD is an incredibly lonely journey which kind of forces you to reflect a lot about your life and what it is you want to do.”

By this time he knew he wanted to return home and improve the healthcare system in South Africa. He was a doctor now and could help patients but he knew he didn’t want to just see one patient at a time. He could do more.

“I’d always been entrepreneurial. However, the nature of our academic programmes was not to support anyone who had an interest in business. I recognised that I lacked the commercial attitude that would help me realise and bring the kind of projects that I had in mind to life such as Quro.”

Vuyane enrolled in the Saïd Business School MBA at Oxford shortly after completing his doctoral studies. He would meet one of his co-founders and Quro’s Chief Scientific Officer, Rob Cornish during this MBA.

Vuyane returned to South Africa ready to start a business that would change the healthcare landscape forever.

Starting Quro and entrepreneuring while black in South Africa

Before starting Quro, Vuyane had tried setting up another tele-medicine startup with his friend, business partner and Quro’s co-founder and COO, Zikho Pali. The venture didn’t go far but it did provide a good springboard for the work they would eventually do.

In April, Quro announced they raised $1.1 million in a seed round. This was huge for many reasons.

On one hand, Quro finally had capital to begin expanding their services across South Africa and beyond. On the other hand it marked the beginning of a relationship with investors who were truly interested in their wellbeing.

“One of the things that Zikho and I reflect on quite a bit is the manner in which the investors that we’ve got engaged with us. It was a clear reflection that they didn’t subscribe to the kind of belief systems and whatnot; that we see with white South Africans, given the history and culture of apartheid.”

With a brilliant idea to bring healthcare directly to patients at home and the numerous use cases the pandemic helped explore, I tried to find out from Vuyane what were some issues he’d faced in pushing a solution that I believe should have guaranteed support on all fronts.

“I didn’t realise how being black would count against me,” he said.

“Here I was, having done all that people usually say you need to do; get yourself a solid degree, be on a prestigious scholarship, get yourself an MBA, if possible.

I checked all of those things that people say contribute towards your success as an entrepreneur and people wanting to back you.”

But the reality for black entrepreneurs like Vuyane in South Africa is that they need to go through even more hurdles to get a chance to be listened to.

He highlights a culture where black entrepreneurs are not getting ‘backed’ in the real sense. Many people are offered ‘mentorships’ but this is rarely followed up with actual capital.

“Jeff Bezos, Steve Jobs and all of these guys, none of them were backed because they had a single idea and they made zero mistakes, backing someone recognises that you’re going to make mistakes and you’ll pivot as part of the business.

However, when we look at the opportunities that have been given to black entrepreneurs in this country, across Africa, you’re not being backed. You’ve been given one miracle, and you’re asked to make a wish. And your role is to try and make sure that you don’t make those mistakes. And I do think that that’s the culture that needs to change, that when we talk about backing black entrepreneurs and African entrepreneurs in particular, we need to make sure that we do just that, that we provide an ecosystem for them to learn.”

An African solution to a global problem

Vuyane loves to cook. He also loves to travel. These are things he does often and, as soon as it is possible, he hopes to do soon. He would like to visit countries in West Africa.

When I ask what plans he has for Quro’s expansion across Africa, he gives what I consider a poignant answer.

“I always push back when people say this is an African solution to African problems. This is a global problem. We’re seeing this everywhere. So in our context, it may be an African solution to a global problem.”

For Vuyane, the goal is simple – to take over the world.