Car manufacturers in Egypt have had to cut down on production due to a recent lack of electronic control units (ECUs), which are major components in vehicle electrical systems. In South Africa, more than 20,000 people that signed up for Supersonic’s Unlimited Air Fibre service are still waiting to be connected since February, as the company continues to face difficulties getting crucial router components.

The aforementioned companies operate in two distinct industries (automobile and ICT) and – apart from the consumers they sell to – do not really have much in common. But like many others in several industries across the world, they have seen their businesses disrupted by the same problem.

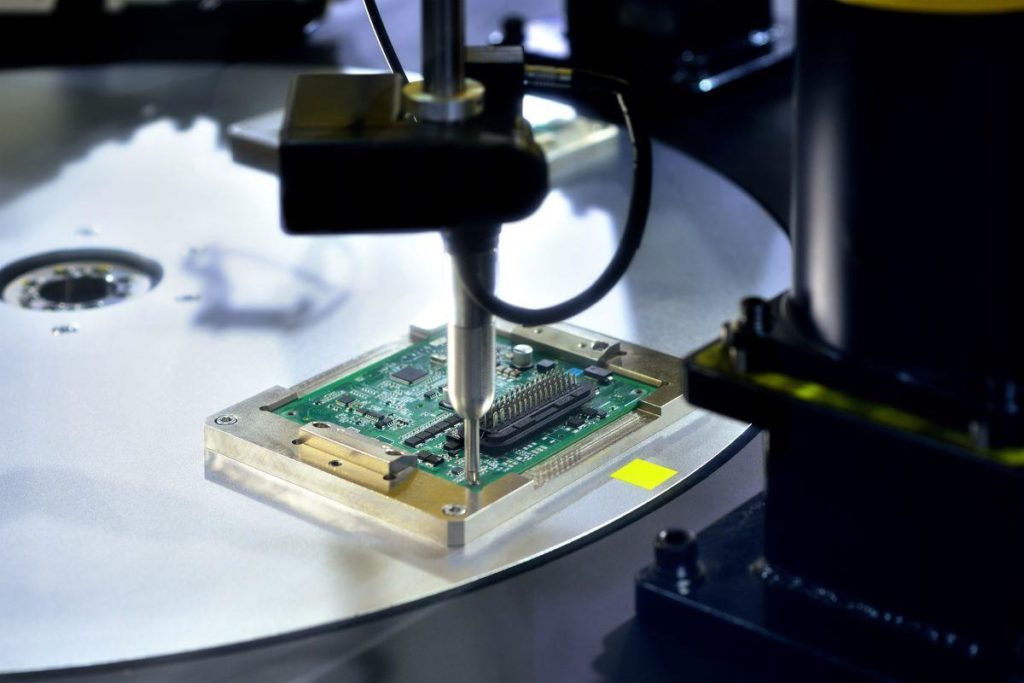

Technology companies globally have recently been grappling with the shortage of one of the smallest components used in producing millions of tech products yearly – semiconductor chips.

Months into the shortage, effects from the ongoing global chip scarcity have spread far and wide, across industries and the globe. Automotive and consumer hardware companies are being hit the worst and those in Africa have not been spared.

Distributors of Acer products in South Africa – Mustek, Rectron, and Homemation – told ITWeb that the severe shortage has caused a ripple effect across all industry verticals, leading to a shortage of laptops, tablets, printing and scanning equipment, and peripherals.

Price jumps as over 100 industries suffer

An analysis by U.S. investment bank, Goldman Sachs, estimates that the semiconductor scarcity affects a staggering 169 industries in some way. This is due to the fact that chips are more widely used today. They used to be present in only personal computers and mobile phones a little over a decade ago. Now, in the wake of rapid digital advancements, semiconductors are in everything from vehicles to washing machines.

Manufacturers have struggled to keep up with the huge demand in recent months, a problem blamed partly on supply chain disruptions caused by national Covid-19 lockdowns, uncertainties stemming from the U.S.-China trade war, as well as a drought in Taiwan, home to the largest semiconductor maker in the world.

In fact, Taiwan is one of the four countries in Asia behind nearly three-quarters of global semiconductor manufacturing capacity. Of these countries, only two produce the most cutting-edge chips.

The Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) alone provides 92% of cutting-edge chips globally – with Samsung accounting for the rest – and 60% of chips used by automobile companies. This leaves companies with few options to get chips when the producers run out of capacity and also raises concerns about the concentration of chip manufacturing in relatively few countries.

U.S. tech giant Apple has been significantly affected as it is one of TSMC’s biggest clients. In South Africa, many stores run by the company’s authorised reseller, iStore, have reportedly experienced shortages in iPhone stock. Meanwhile, TechCabal was unable to reach the Nigerian unit of iStore for comments as of the time this article was published.

Going by the law of demand and supply in economics, there is bound to be an increase in the price of a product when there’s a scarcity, as long as all things remain equal. So the global chip shortage has naturally led to price increases and there’s not so much local players can do about it.

“These are not components domestic car makers can produce,” head of the Egyptian Association of Automobile Manufacturers, Khaled Saad, reportedly told local press. “The problem is already putting pressure on car prices domestically and it is expected to raise prices further.”

Reports show many local stores in South Africa are now selling well above the retail prices suggested by manufacturers.

According to David Kan, CEO of Mustek, the ongoing shortage is the worst in more than three decades. “In my 34 years of working within the IT industry, I have never experienced or seen such shortages. Pricing has gone through the roof!”

Any end in sight?

The multifaceted global chip shortage problem is showing no signs of abating.

At the beginning of the year, there were hopes that the supply chain issues would have been sorted by the summer. However, it is unlikely that will be the case, even though the summer does not end until September.

Industry analysts also can’t seem to agree on when the shortage will end, with predictions ranging from the second half of 2021 to the beginning of 2022. Some experts say the effects of the crisis could last well into 2023. However, the general consensus seems to be that things will get even worse before it gets better as there is no immediate solution.

Some global chipmakers – such as TSMC, Samsung, and Intel – are already investing to expand their capacity and ramp up production. The U.S. is also working towards investing billions in its semiconductor manufacturing.

In Africa, Kenya’s Dedan Kimathi University of Technology partnered with American firm 4Wave Inc on the launch of the country’s first semiconductor factory earlier this year.

A future partnership between local car agents and brand owners to set up local facilities for manufacturing high-tech components like semiconductors is also being mooted among automobile stakeholders in Egypt.

But these moves can do little to ease off the crisis immediately as it will take months, if not several years, for the investments to mature.

For now, tech products are bound to keep fighting for limited chips, manufacturers grappling with delayed production, and consumers suffering from shortages and price increases.

Did you enjoy reading this article? Please fill out this survey. We need your feedback to help us introduce content you will find useful.