To understand how Ato Bentsi-Enchill started investing in startups, let’s rewind to 2014.

He was a first-year liberal art major at Hobart and William Smith Colleges who won the school’s flagship business plan competition. The business idea was RevisionPrep, an online educational service that combined exam preparation with gaming programs for students in Ghana.

It was a sign that he had business acumen – an ability he nurtured while working for his entrepreneurial parents. His grandfather’s company, Black Adam Distilleries, would inspire his current company’s name: Black Adam Africa Capital Management, a boutique investment firm specialising in private equity, investment advisory and project financing.

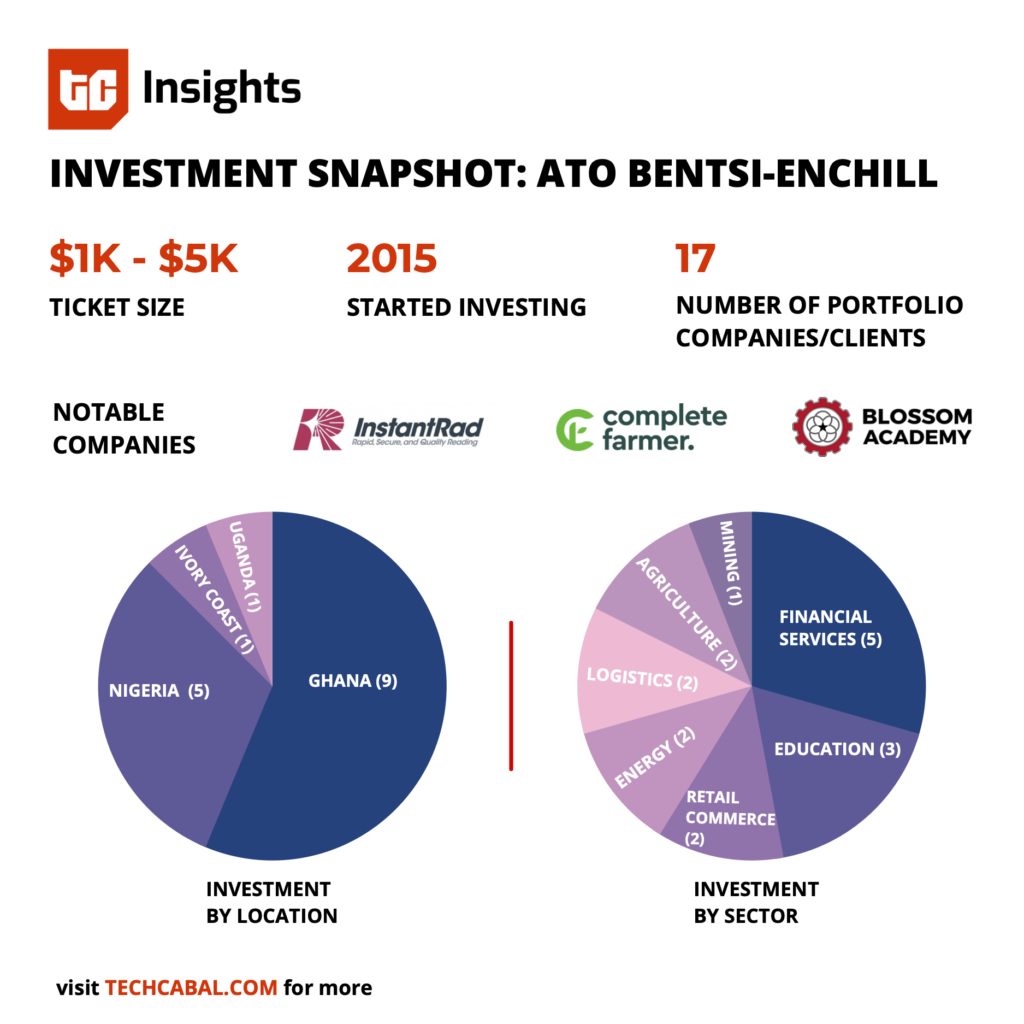

Bentsi-Enchill also invests in startups personally and through syndicates like Future Africa and Rally Cap. He’s also a Venture Scout for Microtraction.

Our conversation begins with how this current phase of his life started.

Daniel Adeyemi: How and why did you get into investing in companies?

Ato Bentsi-Enchill: I finished college and moved back to Ghana to work on RevisionPrep. After some time, I realised that it wasn’t going to work. So I shut it down and started thinking about what to do next.

But while in the US, I had attended many Africa-focused business conferences at business schools at Harvard, MIT, Wharton, Stanford and NYU. I was thrilled to understand the power of private capital to transform businesses in Africa. I made life-long connections with individuals who ended up becoming mentors to me in the space.

Once in Ghana, I started looking at businesses that I thought were interesting enough to invest in if I had that type of money. I wrote summaries and sent them to my investor friends outside Ghana. My pitch was that I could make introductions and help with due diligence if they chose to proceed with the engagement because I was on the ground.

I didn’t close any deals in the early days. I came close to sealing a deal with a gentleman who ran a shea butter processing factory. In a couple of weeks, I had brought in one of the most prominent family offices in South Sudan to look at the deal. They were interested, but the timing wasn’t ideal. The business owner said he liked the way I sourced investors, and if I took this seriously, I could make something out of this.

DA: So when did your big break happen?

AB: I met some investors who wanted to back a fintech company. I helped them with the due diligence, and they decided to invest about $3 million in the startup.

I realised the founder needed more than $3 million during the process, and we agreed I’d help raise more. Initially, he was hesitant as many folks had approached him with similar propositions, proposing hefty retainers while not doing the work.

I was very convinced that this founder will be successful and told him to forget the retainer; I was ready to work with no payment upfront. Thankfully within a year and a half, we raised $7.5 million (up to $15 million now). Unfortunately, they didn’t announce this deal, so I can’t disclose the name. However, that engagement gave me better insights into analysing companies and making my bets on founders at a very early stage.

Initially, when I started investing in companies, I made some mistakes and lost a lot of money, but I believe these lessons have helped me hone my craft. I’ve also just concluded my first scout investment for Microtraction, a deal I also invested in.

DA: You’ve moved from a liberal arts background to business and investing in startups. How did you learn all these?

AB: In the early days, when people asked me to do valuation reports, I got initial guidance on YouTube, read as many books as I could on the topic and spoke to people in my network. It’s been more of self-education, and I believe that works best for me, although an MBA will be necessary for the future.

Sometimes potential clients look at my background and are skeptical but I tell them results don’t lie. I’ve done some solid work with my clients, and they are some of my biggest cheerleaders.

DA: What do you look out for when you want to invest in a company?

AB: For early-stage investing, the first thing is the team; I try to understand their motivation to build this company. Not everybody can run any company. Do they have deep knowledge of the industry? Are they resilient?

The second thing is the size of the market. Companies in Ghana have a more significant challenge in executing, so I’d try to know what’s unique to this firm and their potential for scaling quickly across their desired markets. If I can see them being a big player between 5 and 7 years, that’s a good sign.

I’m also big on understanding how a company can become a monopoly in their space. And by monopoly, I don’t necessarily mean how they become the next Amazon (although that would be awesome!), but what gives them an unfair advantage against their competitors in the industry. How can they dominate the market despite the presence of competitors/incumbents?

I’d also like to understand their challenges and risks of failure. Of course, they don’t need to have the solutions to all these problems today, but it should be evident that they have given it some thought and come up with a plan.

If they’re not currently making money, I want to know that they’ll make money at some point. I’m not much of a believer in just looking at valuations. Unit economics are also critical; they have to be positive or on the path to being positive.

I also try to find out why now is the right time for your business to exist. What’s happening within your industry? What are your competitors doing? What do your customers want? Once there’s a convergence of needs, there’s a good chance your company will succeed.

Today, I’m a very new angel investor in a space that’s becoming increasingly competitive. I’m happy to invest between $1-5k in companies at pre-seed and seed levels. These may look like small amounts, but it’s always best to start small and learn; you’re going to lose money along the way.

Plus, if you are able to show how you can be an asset to these companies and have a credible story as to why they should take your money versus all the other monies being thrown at them, you’ll be in a good starting position.

One other thing I did very early in my journey is to learn to write investment memos. I reviewed memos from Sequoia, a16z and Bessemer Ventures to understand what exactly to highlight when presenting a company to an investor.

DA: How do you conduct due diligence?

AB: Definitely I want to see their audited reports; for me, the numbers tell the whole story. But even when you’re looking at numbers you need to look deeper.

A lot of people say they made x amount of sales, they don’t classify it as gross or net. Depending on their business, was it the amount their clients collected, of which a smaller percentage came to the company itself? It’s important to know all these things.

I’m also curious about how money has been passing through the bank account over time. When you understand the business model and their cash flow situation, you can sniff out pertinent questions that make the story clearer to you.

Now a lot of companies are sending links of articles on TechCabal or TechCrunch of similar companies in China, India or the US, to add credibility to the valuation or the business model. I don’t really buy that. You can’t use the fact that someone raised $100 million series B as a pointer that you’ll get there. We all know the market in Africa is different.

It is definitely possible, but I won’t lean heavily on the fact that a company with a similar business model has succeeded in a market. If I looked deeper, I’d probably see 99 other companies that failed doing the same thing. What shows that you won’t be part of those 99 in Africa?

Other important due diligence points are talking to customers, running reference checks and spending as much time as possible with the founders to see how they run their business on a day to day basis. It takes me between one to three weeks to sort out due diligence.

DA: How do people find you?

AB: Hmmm. Primarily through my newsletter — musings of a wannabe African VC, LinkedIn or through referrals from previous clients or people in my network.

I also reach out to people. I’ve reached out to a podcast host before to introduce me to a guest who I thought would need my services and it resulted in an engagement.

At this point, it’s important to mention that I don’t take on everyone, either because my team and I don’t have the capacity to or I’m not too convinced on their business.

DA: Are there some sectors you don’t invest in?

AB: Naah. Once I can understand your business model, I can raise money for you or invest. I don’t think it’s wise to restrict myself for now.

DA: So what’s your value add to businesses outside of just raising money for them?

AB: I first connect people to capital, but beyond that, I help them understand what they should be focusing on and thinking about the different ways they could be building their business.

For example with InstantRad, outside of helping them engage investors, I do a lot of business development work for them. I also help companies build a path to exit; It’s something a lot of people don’t understand. Anyone who gives you money is also thinking about how to take it out at some point, so having a workable plan (that of course can be changed depending on market conditions) helps keep everyone focused.

I help founders with term sheet analysis. There’s a lot of technical terms that investors can slip in that young founders aren’t aware of.

DA: In layman terms, please give some examples of these technicalities?

AB: There are good and bad investors. I’ve seen some pretty horrible term sheets that don’t have the founders’ best interests at heart. I’m always on the side of getting the deal done, but it has to be fair. I’ll be the first to speak up when something on a term sheet does not look right.

For example, investors often offer startups convertible debts – a loan that could be repaid or converted to equity at a later date. Now I’ve seen some term sheets where the investors ask that if the founder opts to pay back the investment, the investor gets some amount of free equity in the company. For quite a high-interest rate and no additional value, the investor wants more equity in the company? Make it make sense.

I walked the entrepreneur through the term sheet and we ended up not taking capital from that investor.

I’ve also seen term sheets where investors are asking for four times (4x) liquidation preference. This means that if for any reason the company has to go through any kind of liquidation, the investors will get four times the amount they invested and the founders could possibly be left with little or nothing. No matter the kind of risk the investor is taking on the founder, I don’t believe someone who’s spent their blood, sweat and tears building a company should possibly be left with nothing. To me, investing in a company means you’re sharing the ups and downs of the company, and it’s a partnership.

These terms aren’t necessarily unfair. It could make sense in certain scenarios as investors are trying to get as much equity from the company. But beyond affecting founders, these terms also affect future investors who could be discouraged from investing.

DA: What trends are you seeing in Ghana?

AB: Because of its market size, Ghana may not dominate one sector the way Nigeria does in fintech or Kenya in agritech. For the most part, I think we will be in the middle. Maybe number two or three in these sectors.

That said, the future is exciting.

One of the biggest success stories out here is mPharma, and it’s unfortunate that most folks may not know that they’re a Ghanaian company. They didn’t just stay in Ghana and call it a day, they expanded to Nigeria and Kenya. Using mPharma as a reference, I believe startups here have to expand to different countries.

Zeepay is also doing a good job in respect to expansion, they just raised their $8 million series A. Based on my inside knowledge, I think there are other companies like Zeepay that have a good shot at expanding at a rapid rate. I’m confident we’ll see companies like that exit in the next 5 and 7 years as the market grows.

If you enjoyed reading this article, please share in your WhatsApp groups and Telegram channels.