You cannot wish a digital economy into existence!

Africa is at a digital crossroads. With more people and businesses embracing and depending upon connected digital tools to make everyday decisions, manage sprawling business interests across vast distances and deliver digital content reliably, the continent’s plan for interacting with a cloud-based world needs a radical makeover.

Africa’s need for a do-over in how it treats data centres is not about data sovereignty, localisation, or the physical vs cloud debate. It is simply about powering the expected growth in a promised digital economy bonanza and deliver that vision in as seamless a manner as possible.

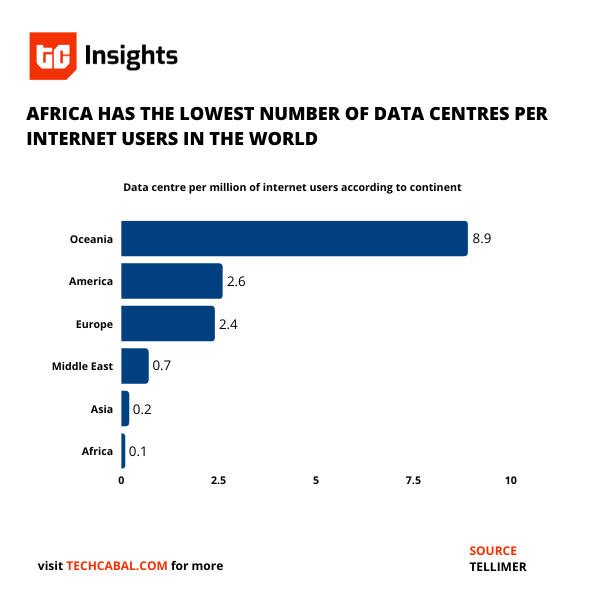

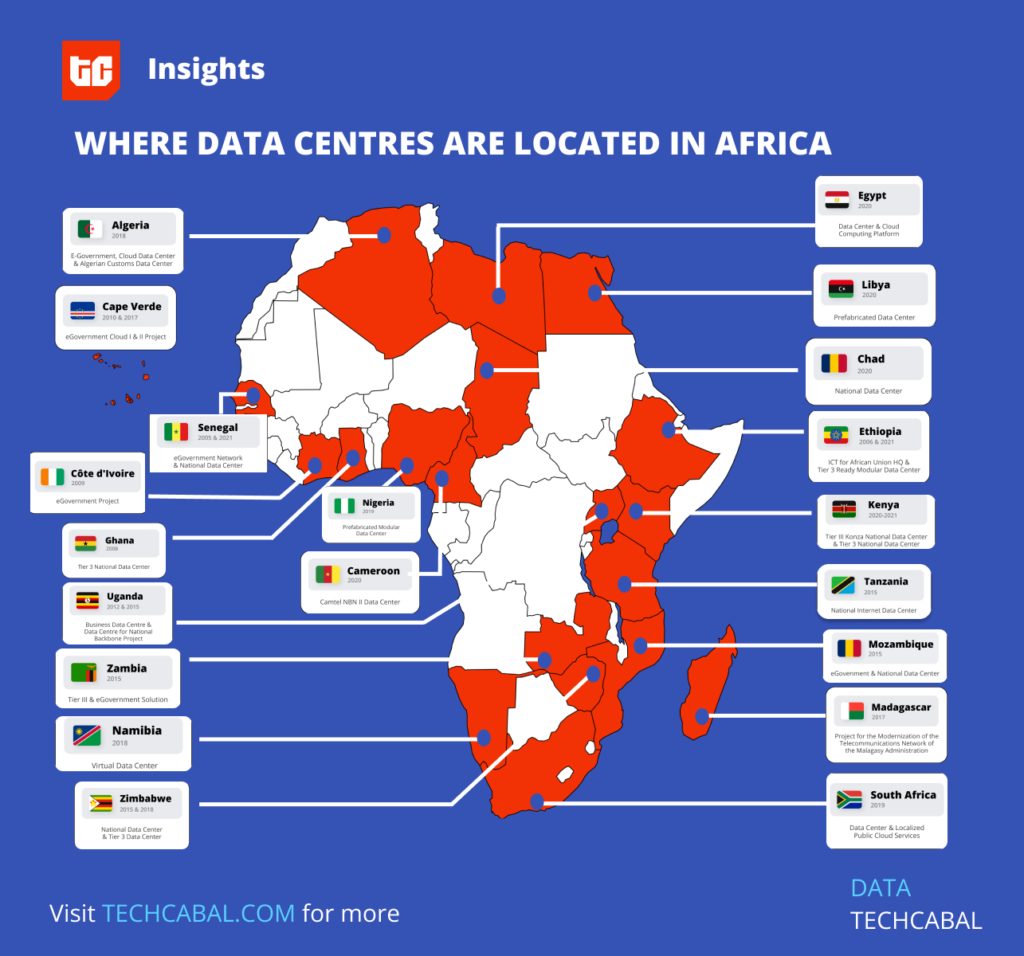

More than 30 Tier III and above multi-tenant data centre facilities have come online across the continent since 2016. On the surface, this is an impressive twofold increase in the region’s hosting capacity. But this capacity is uneven. Only a third of Africa’s 80-plus cities with a population of more than one million have at least one data centre facility at Tier III standard. More than two-thirds of the continent’s capacity sits within South Africa—with Nigeria, Kenya, Egypt and Morocco coming behind.

At the same time, Africa’s broadband user base is expected to double in 10 years, driving demand for smooth “transportation”, warehousing and access to data on demand.

Read: Babajide Ogunjobi joins VerifyMe as Vice President of Products & Data Strategy

The heart of failed data centre policymaking in Africa is really a lack of appreciation of what a digital economy looks like. African leaders and bureaucrats are unfortunately used to presiding over shops on the streets, raggedly dressed traders in open-air markets, and a general analogue dysfunction—markers of the time around when most of these leaders found themselves thrust into the political limelight. The problem is that, yes, the street corner shops remain—and even multiply courtesy of worsening economics. And the open-air markets continue to take up more space as more people join the hustle. But the bustle is no longer just happening on the streets.

Like it or not, millions of Africans, beginning from the mid-2000s, have become digital residents of some sort. Young Africans today are almost born digital natives, and the elders are catching up fast. Or put another way, Africa is a digital market still waiting to happen. Infrastructure like consumer software (shops), data racks (warehouses), fibre optic networks (transport) and a finely tuned plan, are all integral to the success—or not—of this market.

Consumer software (by which I also mean the business-facing software consumed by non-technical end-users) in Africa has gotten some celebrity in the past five years, a fact that showed up in the record capital put up by venture investors in 2021. The digital economy that has been played up has mostly been the very fragmented digital “shops” that offer consumer-side software. What has largely gone under the radar has been the build-up of and un-leveraged opportunities in building the warehouses and transport system that will form the arteries and lifeblood of Africa’s digital economy. This policy failure has come from two ends.

- Docile and politically distracted governance

- Frustrated, short-term entrepreneuring

Distracted by non-governance

Data centres need power. Enormous amounts of it. Without more involved government action at national, regional, and local levels, Africa’s power, land, and water requirements for data centre facilities at any meaningful scale will be difficult to achieve.

But African governments are failing to manage this basic requirement. South Africa, the continent’s leader in both power and data centre infrastructure to date, has failed to deal with the crippling crisis that has plagued state-owned power utility Eskom since 2007. The worsening crisis and the government’s inability to deal with the simmering problem are costing South Africa’s economy ZAR4 billion every day (over $220 million).

Instead of focusing on fixing the basic inputs needed to build strong data centre networks, the continent’s bureaucrats prefer to fixate on meaningless—for now—conversations about data sovereignty. Data sovereignty is important, true. But the reality today is that it is the cart.

Read: How OFM intends to build Africa’s largest car inventory database and management system

Gold panning entrepreneurs

People often assume that policy is a government thing, not something that concerns entrepreneurs in the trenches. But all business strategy is policy and all policy is a sum of tradeoffs.

Panning for gold is consuming work. Especially when everyone else is looking for the three-inch ingot that could theoretically get them out of the rat race. Panning for gold in African markets requires extra vigilance. Not least because the government is sometimes fishing for gold dust from entrepreneurs at the same time they are compounding an already difficult situation. The result is that businesses reduce their depth of field, keeping the subject (revenue) in focus, while the background (ecosystem opportunities) is blurred. In short entrepreneurs—even the digital ones become moneypreneurs—working for the next sliver of profit margins that enables them to “maintain beauty”.

Naturally, this state of affairs also motivates a class of entrepreneurs who cannot imagine life beyond their noses, who become so entrenched in the unworkable system, they do not want it to change.

But it does not have to be so. If the big fancy digital economy projections are to even become a worthy moonshot, Africa needs a roadmap for critical data centre infrastructure to power and even precede the growth of user-facing products and content.

Read: How Fintech companies can scale customer support operations

The benefits are far-reaching. First is increased topline revenue for infrastructure providers. But even more than that, a robust data centre and fibre connectivity network across the continent also means better access to cheap internet, stronger trade ties, a deep and wider digital inclusion net, and the opportunity to have realistic conversations about data sovereignty, residency and privacy regulation. I admit that today all of this is a tall order, but it is not impossible. Someone has to think about these things, or sooner or later we will be forced to confront the consequences of simply coasting.

We’d love to hear from you

Thanks for reading The Next Wave. Subscribe here for free to get fresh perspectives on the progress of digital innovation in Africa every Sunday.

Please share today’s edition with your network on WhatsApp, Telegram and other platforms, and feel free to send a reply to let us know if you enjoyed this essay

Subscribe to our TC Daily newsletter to receive all the technology and business stories you need each weekday at 7 AM (WAT).

Follow TechCabal on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and LinkedIn to stay engaged in our real-time conversations on tech and innovation in Africa.

Abraham Augustine,

Senior Writer, TechCabal.