Or the physical anatomy of a digital ecosystem.

In last week’s edition, I claimed that a digital economy is not something Africa could “wish into existence”. This week, I will further suggest that Africa does not have a digital economy; we have a digitally extracted ecosystem. I am not writing this to be brash or counterintuitive. It is simply the reality. Today’s edition of Next Wave will mark out the outlines of a digital economy and what it means to have a sustainable digital economy in the dynamic first quarter of the twenty-first century.

The core of my arguments is a disagreement with the trite definition of “digital economy” that we are used to. A digital economy as “the use of information technologies to create and consume services and goods”, as defined by most results on the first page of a Google search, is flawed because it leans too heavily on economic consumption.

The practical application of this distorted consumption narrative today has forced us to focus solely on unicorns and “digital transformation”. It is an honest but lazy attempt at overviewing the complex networked state that is a functional digital economy.

A side note: this unsustainable focus, and the abundant perverse incentives in a world of easy credit and Keynesian monetary cycles, is why “tech stocks” divorce economic sense in “good times” without paying alimony.

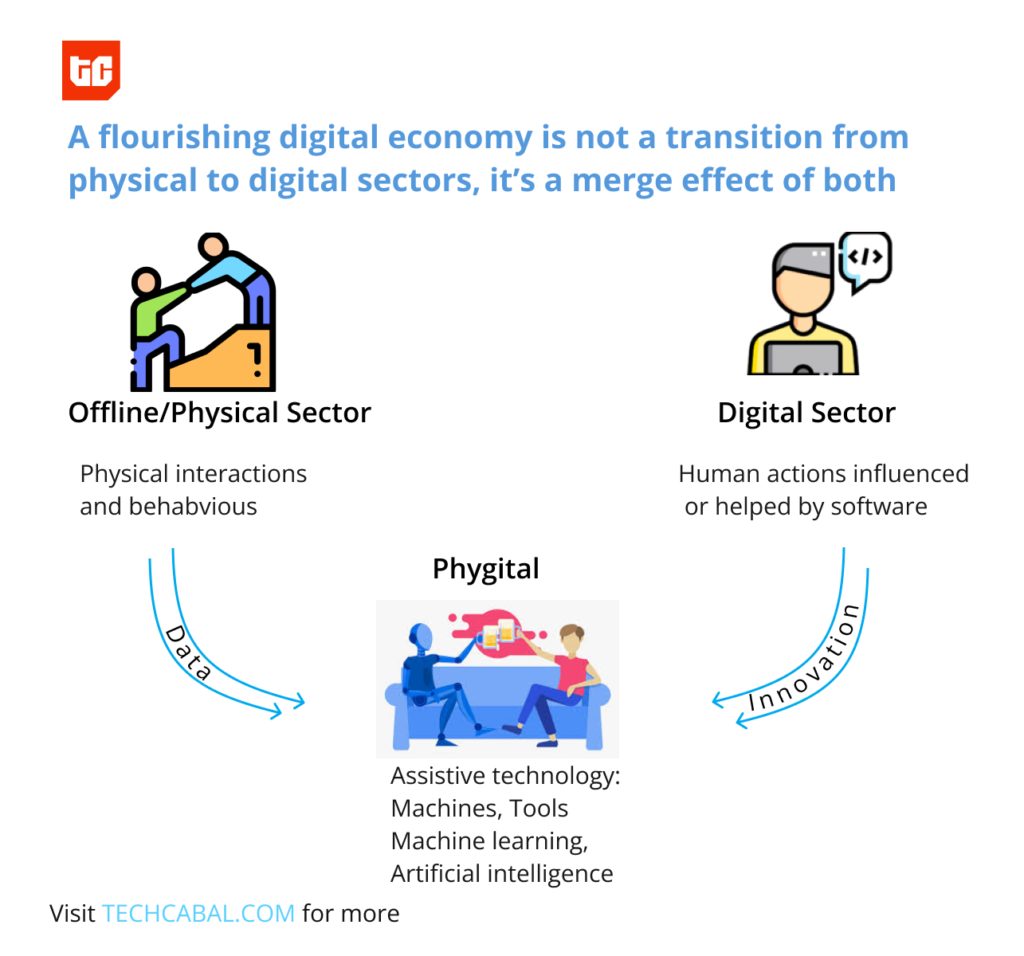

A digital economy is not just “the economic activity that results from billions of everyday online connections among people, businesses, devices, data, and processes”;[1] it is also how the creation and use of digital channels reshape economic, social choices and legal considerations in entire societies. Inevitably, a digital economy is about how physical actions, behaviours, communication, markets and choices are distorted by the use of digital infrastructure. In much the same way as a paved road that connects a struggling rural community to a thriving city can reshape the options for the residents of that community. From this view, it is easier to appreciate more of the nuance that shadows a digital economy.

If, “the heart of failed data centre policy making in Africa is really a lack of appreciation of what a digital economy looks like”, then what does a digital economy look like?

Digital economies: A crash course in anatomy

Broadly speaking, because I intend to serialise these conversations in more extensive essays, a digital economy is built on at least four columns:

- Digital infrastructure and the means to make, control and maintain them.

- Network effects and a system for managing the results of these effects.

- Legal infrastructure.

- Institutional committment to intentionally addressing the social questions that digital economies raise.

These four pillars arise from the fact that a digital economy interacts with physical behaviours and tools that are captured and digested by software. But also because software is not just a passive garbage-in-garbage-out affair, a digital economy recycles software data and human reactions into how it manages production, regulation and consumption. Social media, (a euphemism for network effects of all kinds, including Uber) for example, has demonstrated that the software layer induces and supports human behaviour in an ever-widening circle.

Data is the connector and as computers get better at classifying natural data, we are training them to react to all these interactions.

In Africa, where the race to digitising x is heating up, it is easy to miss that the hardest part of building a digital ecosystem is not in driving adoption. The consequential pieces of a digital economy are physical, rooted in human behaviours, geopolitics, and the ownership of the enabling infrastructure.

First foundations

One risk that comes with building a technology ecosystem that is heavily reliant on software investors is that we may get carried away and let software VCs define what a digital sector is. The good news is that Africa’s digital story has an infrastructure background that younger tech entrepreneurs and operators will do well to study.

The bad news is that by being dependent on foreign capital and associated whims, building for Silicon Valley or creating shiny African replicas of Silicon Valley products is in full drive.

Ecosystems don’t prosper by transplants. Exotic species often become invasive and threaten natural fauna.

The problem with a software-defined digital sector is not peculiar to Africa—with the turn of the century and following the IPOs of Google and Facebook, technology thinking in the West largely abandoned non-software innovation—at least to the casual public eye—in favour of mobile and web applications.

“Software is also eating much of the value chain of industries that are widely viewed as primarily existing in the physical world,” declared investor Marc Andreessen in his popular 2011 blog post. That “software is eating the world” became the mantra which many VC investors lived by.

The problem, of course, is that software is not really only software, and except you believe that we have reached peak hardware, much of the value of software depends upon things that are impossible to turn into code. Like digital infrastructure (not APIs), competition and market structures, human behaviour and laws, and the energy that makes electrons move through silicon.

“The global supply chain disruption reminds us that much of the economy is built on physical goods. So, why is it that software companies get most of the technology industry’s attention?” Jonathan Levine, co-founder and CEO of Folia Materials asked, in an article published in January this year. That this article was published by 500 Global, a venture capital firm with major investments in software highlights growing concerns about how vulnerable value creation with software is if there is no corresponding growth in the physical systems that people need to use the software. People don’t eat applications.

In the relatively short history of venture capital, physical innovation played and continues to play a fundamental role. Indeed, in the early days, some of the biggest VC-backed tech was more physical than software—hence “Silicon” Valley. Beyond this foundation, what is more important to note is that the basic innovations that undergird today’s digital economy (like the internet), were the results of publicly funded IP that devised the tools that make a digital economy possible, and enormously profitable.

The subtext to this is that a digital economy is a creation of intentional and institutional design that is also liberal enough to allow for some organic flow—especially at the commercial layer. This commercial layer is where venture capital and entrepreneurs—which we better associate with a digital economy come in. Everything that precedes this are equally important parts of the story.

This context is what Africa lacks, and more importantly, what Africans should not be in a hurry to “leapfrog” or worse disregard because “we want to specialise in our strength”.

Build castles neither of sand, nor on sand

I have tried to illustrate in the preceding paragraphs that a digital economy is a complex creation that is being embedded into the core of physical systems. Building a digital economy—not a digital sector of the economy—is hard complex work. It is not a label. It is also not something that an inefficient and corrupt political class can comprehend, nor is it a short-term “capacity building” project.

Unfortunately, we have to start with poor physical systems in energy, roads, homes, health, education, and even water supply—the basics. These components are where Africa’s digital economy will begin. Or we’re simply feeding from borrowed troughs.

My primary school library had several copies of Silver Burdett & Ginn reading textbooks. One of my favourites was the 1989 hardcover edition of Castles of Sand for Grade 8 pupils. On the cover illustration, a mini stream flows underneath a cute shell-decorated sand castle on the beach as a puppy looks on in surprise. It looks like a castle, complete with seashell decorations. The major difference is not that it is made of earth but that it is made of a type of earth—of sand.

References.

1“What is a digital economy?” Deloitte Malta.

https://www2.deloitte.com/mt/en/pages/technology/articles/mt-what-is-digital-economy.html

We’d love to hear from you

Psst! Down here!

Thanks for reading The Next Wave. Subscribe here for free to get fresh perspectives on the progress of digital innovation in Africa every Sunday.

Please share today’s edition with your network on WhatsApp, Telegram and other platforms, and feel free to send a reply to let us know if you enjoyed this essay

Subscribe to our TC Daily newsletter to receive all the technology and business stories you need each weekday at 7 AM (WAT).

Follow TechCabal on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and LinkedIn to stay engaged in our real-time conversations on tech and innovation in Africa.

Abraham Augustine,

Senior Writer, TechCabal.