First published 03 March, 2024

Edtech gained more popularity during the COVID pandemic, with many edtech startups—Nigeria’s uLesson and South Africa’s Foondamate, for example—thriving during the period. Between 2020 and 2021, funding for the edtech sector grew from $14.7 billion or 831 rounds in 2020 to $20.3 billion or 1,050 rounds in 2021—the highest peak in the sector. A few startups in that industry, like uLesson and Foondamate, targeted their services at pre-university pupils, often called K-12. But by the end of 2021, edtech’s initial use case for K-12 started to wobble.

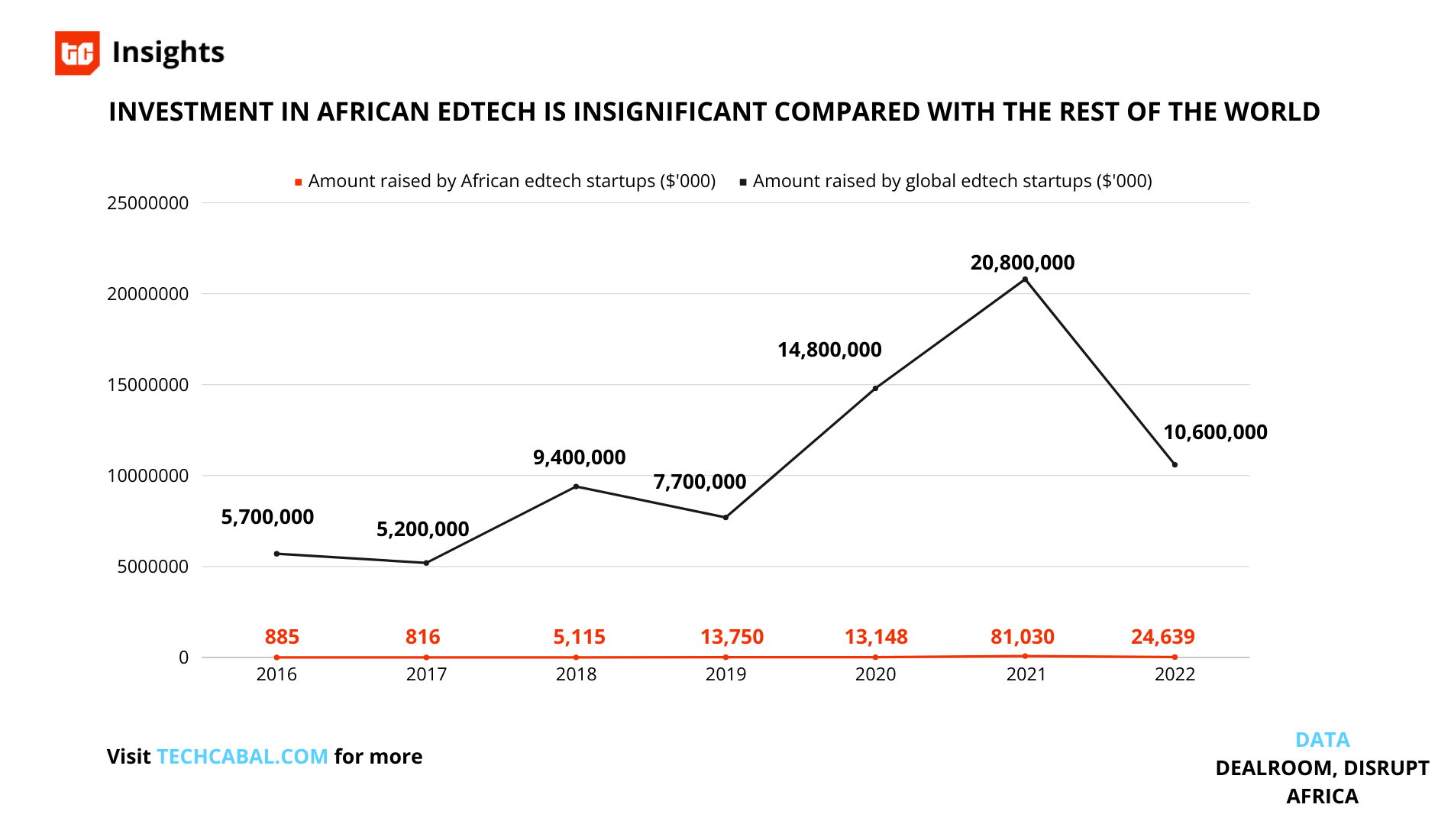

Investment in edtech startups in the last seven years. Chart by Stephen Agwaibor, TC Insights

In 2022, edtech startups in Africa raised only $24.6 million or 0.7% of Africa’s total funding, according to data from Disrupt Africa. In the Big Deal’s report for January 2024, the only mention of edtech was an acquisition of Egyptian edtech Orcas by Baim, for an undisclosed amount. The rest of the report showed that agritech, fintech and climate tech attracted the most funding in January. In 2023, no edtech company was able to raise a venture round of $100 million or more, per Crunchbase. Year-to-date, global funding for edtech startups has fallen 89% to $2.2 billion or 232 rounds.

Edtech has lofty aims, but there is a big question about whom the industry should be serving.

Whom should edtech serve?

Beyond the scary tale of a funding dry-up, what we are seeing here is edtech undergoing an interesting pivot many may have ignored. As the world healed from COVID, parents no longer needed or trusted digital schooling for their kids as much; they mostly found it to be an unnecessary extra expense added on to fees paid for brick-and-mortar schooling. uLesson, in recognition of the economic hardship its clients are facing, recently slashed educational software subscription fees by half indefinitely. But palliative moves like this can only do so much to boost the clientele of K-12 edtechs.

Why?

Physical schools are not going away anytime soon. Children have time to commit to the physical demands of learning; parents would therefore rather enrol their kids in a setting where their learning is easier to monitor and where there are minimal distractions. Besides, physical learning will always be a welcome development where screen time can cause eye fatigue and shortsightedness.

Partner Content:

Read: How Filmmakers Mart is changing filmmaking in Africa by solving production problems

here.

All that said, working professionals may be a stronger market for online education providers, as they either need to juggle necessary part-time education with full-time jobs; or get a skill-driven education in order to advance their careers. Thanks to our current learning economy, working professionals are upskilling towards in-demand roles, consistent with a reconfiguration of the labour market rooted in technological adoption. A 2021 Workplace Learning Trends Report by Udemy revealed that industries have increased demand for data analysis and data science expertise.

Data like the above may be responsible for why edtech companies focused on skill-driven education for working professionals are either successful (AltSchool) or will be (Miva University).

Next Wave continues after this ad.

In recent times, Nigerian edtech startup, AltSchool, has garnered public trust with a track record of supporting about 60,000 learners across 105 countries since its inception in 2021. Its curriculum covers business, data, engineering, media, and the creative economy. Many of these courses are sought after in today’s work industries.

Miva University, a Nigerian online university by the founders of uLesson, currently offers courses like cyber security, data science, software engineering, and business management—all listed as in-demand disciplines under the World Economic Forum (WEF) future of work in 2023.

One of the goals of Miva University, according to its website, is to award its students degrees that get them hired. If edtech will thrive in 2024, it is worth considering that the days of schooling under-16 kids online may be well behind us. The parents who wield the power, resources and disposition to sign their children onto these platforms are more inclined to restrict their kids’ internet use. This is in contrast to working professionals whose concerns are tilted towards using education, by any means, to upgrade their skills.

The future of edtech must therefore shift towards employability and the honing of skills that would matter in the future of work. Africa’s population is poised to double by 2050. With a median age population of below-20, this represents a huge talent pool that, if well harnessed by education, can fuel much-needed innovation.

Joseph Olaoluwa

Senior Reporter, TechCabal

Thank you for reading this far. Feel free to email joseph.olaoluwa[at]bigcabal.com, with your thoughts about this edition of NextWave. Or just click reply to share your thoughts and feedback.

We’d love to hear from you

Psst! Down here!

Thanks for reading today’s Next Wave. Please share. Or subscribe if someone shared it to you here for free to get fresh perspectives on the progress of digital innovation in Africa every Sunday.

As always feel free to email a reply or response to this essay. I enjoy reading those emails a lot.

TC Daily newsletter is out daily (Mon – Fri) brief of all the technology and business stories you need to know. Get it in your inbox each weekday at 7 AM (WAT).

Follow TechCabal on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and LinkedIn to stay engaged in our real-time conversations on tech and innovation in Africa.