Africa’s relationship with technology underwent a structural shift in 2025. After decades as a net consumer of imported devices, networks and energy systems, the continent is increasingly treating hardware manufacturing as strategic infrastructure rather than an industrial afterthought. What began as scattered experiments in phone assembly and solar panels is now converging with a much larger transformation: the rise of hyperscale digital infrastructure, energy-backed data centres and continent-wide fibre systems that demand local production at scale.

By the end of 2025, this shift had taken on far greater significance. Africa’s hardware push was no longer just about lowering costs or creating jobs, but about who controls the physical backbone of the digital economy. As data centres, fibre networks and energy systems become critical national assets, local manufacturing is increasingly tied to questions of resilience, economic security and technological sovereignty. The ability to build and maintain these systems at home now shapes how much value African economies retain from digital growth, and how dependent they remain on external supply chains.

Smartphones, chips and the limits of leapfrogging

Early attempts to localise electronics manufacturing exposed both the promise and the limits of Africa’s industrial ambitions. Rwanda’s Mara Phones project, launched in 2019, is a defining case study due to the scale of ambition and promise to succeed where similar projects have failed in countries like Nigeria due to poor funding and government buy-in. The Kigali facility locally manufactured motherboards and sub-boards, a rare achievement that symbolised industrial sovereignty. But the economics were unforgiving.

Priced between $130 and $190, Mara’s devices struggled against cheaper Chinese and Korean alternatives in a market where smartphone penetration hovered around 15%. Despite creating skilled jobs and proving technical capability, the project ultimately buckled under global price competition.

Kenya adopted a more pragmatic approach. In late 2023, East Africa Device Assembly Limited (EADAK), backed by Safaricom, Jamii Telecommunications and Chinese partners, opened a large-scale assembly plant in Nairobi. Instead of aiming for premium differentiation, the facility focused on volume, cost efficiency and logistics, producing affordable 4G smartphones at around the $50 price point. Within its first year, the plant produced more than one million devices, validating a strategy that prioritised scale and demand aggregation before deeper localisation of components such as batteries and circuit boards.

By December 2024, the Athi River-based plant, operated with an annual capacity of up to three million units, surpassed the one-million-device production mark. This output supported Safaricom’s broader ambition to connect 20 million customers with 4G-enabled devices, contributing to a base of 23 million active 4G devices on its network by late 2025. Favourable government policies helped reduce device costs by about 30%, enabling models such as the Neon Smarta and Neon Ultra, locally assembled and sold by EADAK, to continue to retail for as little as $70 by December 2025. Even so, rising competition from established international brands like Infinix and Redmi limited the venture’s market traction, with local handset market share for Neon smartphones falling to 0.68% by mid-2025.

Kenya has also pursued higher-value manufacturing at the margins. Semiconductor Technologies Ltd, operating at Dedan Kimathi University of Technology, runs one of Africa’s few commercial fabrication facilities producing nanotechnology and integrated circuits for export in partnership with U.S.-based 4Wave. While its current footprint is small, a U.S.-funded feasibility study to expand into legacy automotive and power chips reflects a broader recalibration of global supply chains.

Hardware as the backbone of the green and connected economy

Energy has emerged as one of the most consistent success stories for local hardware manufacturing in Africa, largely because production has been tied to clear, long-term demand rather than speculative industrial ambition. Kenya’s Solinc solar manufacturing plant in Naivasha, operational since 2011, shows how localisation can work when industrial policy, financing models, and market needs are aligned.

The facility produces solar modules ranging from 20 to 250 watts, serving both rural households and a growing urban middle class in search of reliable power. Its expansion has been supported by regional exports to markets such as Uganda and Tanzania, as well as pay-as-you-go financing models popularised by firms like M-KOPA, which have lowered upfront costs and unlocked mass-market adoption.

In 2025, Solinc East Africa further consolidated its role as a regional anchor for solar manufacturing. As Africa’s longest-running photovoltaic producer—a company that manufactures materials and products to convert sunlight directly into electricity—the firm produces over 140,000 solar panels annually at its Naivasha plant, with a total installed production capacity of approximately 8.4 MW.

Solinc moved beyond the off-grid retail segment into larger commercial and industrial projects, supplying systems ranging from 20 kW to over 500 kW. This diversification allowed it to balance high-volume consumer demand with higher-margin industrial installations, strengthening the economic case for energy as one of the most viable pathways for sustainable local hardware production on the continent.

As price gaps between locally assembled panels and imported Chinese modules continue to narrow, purchasing decisions are increasingly shaped by non-price factors. While Chinese products still dominate overall market share, buyers are placing greater weight on warranties, after-sales service, and supply continuity.

At the same time, major Chinese investments in solar manufacturing hubs in countries such as Ethiopia and Egypt are giving rise to hybrid production ecosystems, where foreign capital and technology are combined with African labour and regional markets. Even so, critical upstream components—such as wafers and precision manufacturing equipment—remain concentrated in Asia, underscoring the limits of localisation in the near term.

This hybrid model of global design paired with deep local integration is also becoming visible in other technology-intensive sectors. Zipline’s drone delivery operations in Rwanda and Ghana demonstrate how globally engineered hardware can be embedded into national infrastructure when aligned with public policy and service delivery goals.

Since its launch in Rwanda in 2016, Zipline has reduced blood and medical supply delivery times from hours to minutes, integrating aircraft, software platforms and regulatory frameworks directly into public health systems rather than operating as a stand-alone logistics service.

By 2025, Zipline had evolved from a niche medical delivery startup into the world’s largest autonomous logistics network. The company surpassed 120 million autonomous miles flown without a single injury-causing incident, highlighting the maturity of its technology and operating model.

Its expansion was accelerated by a landmark $150 million pay-for-performance grant from the U.S. State Department, aimed at tripling its reach across Africa to 15,000 health facilities and serving an estimated 130 million people. Zipline also began commercialising its next-generation Platform 2 system for direct-to-consumer deliveries in urban settings, while scaling manufacturing capacity to produce up to 15,000 aircraft annually.

From device factories to hyperscale infrastructure

What truly distinguishes 2025 is the shift from device-centric localisation to systems-scale industrialisation. Africa’s hardware story is now inseparable from the rise of large-scale data infrastructure driven by artificial intelligence, cloud computing and 5G. Total data centre power demand across the continent is forecast to reach 2 GW by 2030, requiring between $10 billion and $20 billion in investment.

“If data is the new oil, then compute is the refinery,” said Alex Tsado, the co-founder of Alliance4ai (Alliance for Africa’s Intelligence), a non-profit focused on making AI accessible and driving African innovation, and also co-founder of Ahura AI, an education-focused AI company, with a mission to build Africa’s AI sovereignty by increasing access to GPU compute and training talent.

“In 2025, we saw a massive shift in awareness among African leaders: the realisation that we cannot solve 21st-century community problems using 20th-century tools,” he told TechCabal.

Kenya’s $1 billion geothermal-powered data centre, backed by Microsoft and G42, exemplifies this new phase. It is not merely a facility for storing data, but a statement that Africa can host green, AI-ready infrastructure at a global scale. Similar dynamics are unfolding across the continent as operators build facilities designed around energy resilience rather than grid dependence.

Connectivity has expanded in parallel. Hyperscaler submarine cables such as Google’s Equiano and Meta’s 2Africa became fully operational, pushing Africa’s total subsea capacity beyond 1,835 terabits per second (Tbps). To carry this bandwidth inland, countries like Nigeria launched a landmark public-private partnership to deploy 90,000 kilometres of terrestrial fibre, while Google announced the Umoja cable linking Africa directly to Australia for the first time.

These projects have radically altered the economics of hardware localisation. Fibre, power systems, batteries and cooling infrastructure are no longer peripheral inputs but core strategic assets.

Nigeria’s fibre moment and the localisation imperative

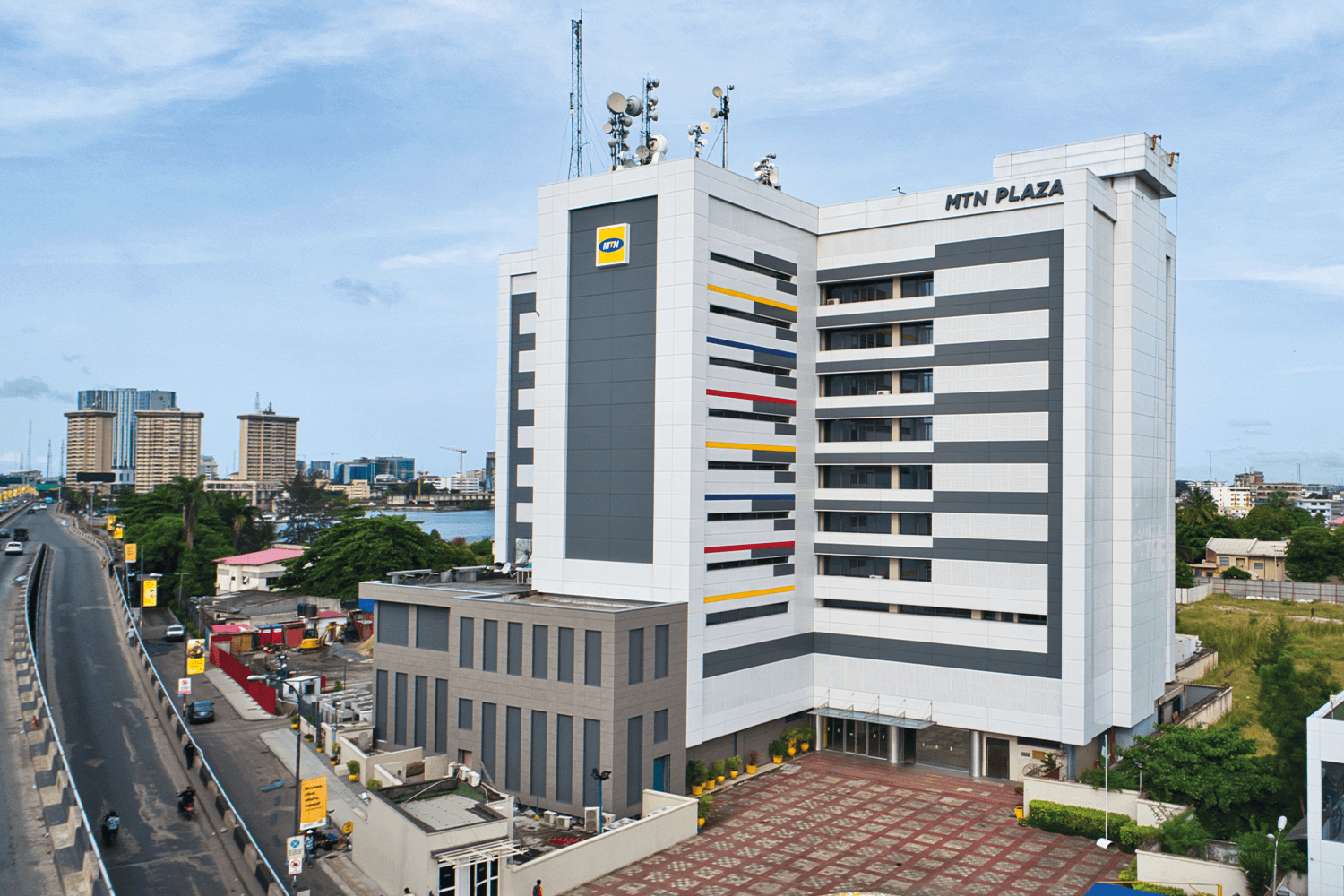

This is particularly evident in Nigeria. In October 2025, Coleman Wires and Cables, a Nigerian-owned cable manufacturer with a 400,000-square-metre integrated production hub, commissioned Africa’s largest fibre-optic manufacturing facility. The plant is capable of producing nine million kilometres of fibre each year—enough to supply roughly half of the continent’s demand. This investment signals a shift from symbolic localisation to industrial capacity at a continental scale.

The rationale is both economic and strategic. Local fibre production reduces exposure to currency volatility, shortens supply chains and supports national broadband ambitions. It also signals that Africa’s hardware future lies less in assembling end-user gadgets and more in manufacturing the invisible infrastructure that underpins connectivity, cloud services and AI systems.

Energy as the final constraint

As digital infrastructure scales, energy has become the binding constraint. Data centres and fibre networks cannot rely on unstable grids. Across the continent, operators are pivoting toward captive renewable energy and advanced storage systems. Teraco’s 120 MW solar PV plant in South Africa and the growing use of modular geothermal power for data centres illustrate how hardware, energy and digital growth are now inseparable.

This convergence represents a significant turning point. Africa’s focus on hardware is moving beyond scattered efforts in phones, solar panels, or pilot-scale fabrication. The continent is now concentrating on the large-scale systems that underpin robust digital economies. For example, Teraco’s 120 MW solar PV plant in the Free State, South Africa, is projected to generate over 354,000 megawatt-hours of clean energy annually, while East Africa Device Assembly Kenya (EADAK) has officially produced more than 1.5 million devices since its launch in late 2023.

A sober reckoning

Despite the momentum, the challenges remain formidable. Most localisation still occurs at the assembly stage, with high-value inputs flowing from Asia. Capital markets remain skewed toward software, leaving hardware and deep tech underfunded. Policy volatility, from tax regimes to local content rules, continues to deter long-term investment.

“The next critical step is for both public and private leaders to move from ‘awareness’ to ‘allocation’—dedicating specific portions of their budgets to sovereign hardware,” Tsado said. “At UduTech, we are leading the way by proving this isn’t just theory. We are already seeing success stories where localised GPU power is being used for critical missions, from monitoring thousands of kilometres of national infrastructure via drone intelligence to powering the next generation of startup accelerators across the continent.”

If anything, the direction is clear. Africa’s hardware push has moved beyond aspiration. In 2025, the continent crossed a threshold, aligning local manufacturing with hyperscale infrastructure, renewable energy and global data flows. The question is no longer whether Africa can build hardware, but whether it can do so fast enough, at sufficient scale, to anchor its digital future.