Project Kuiper, the Amazon-owned satellite internet initiative, has taken a major step toward entering Nigeria’s broadband market after securing a landing permit from the Nigerian Communications Commission (NCC) to begin operations from 2026.

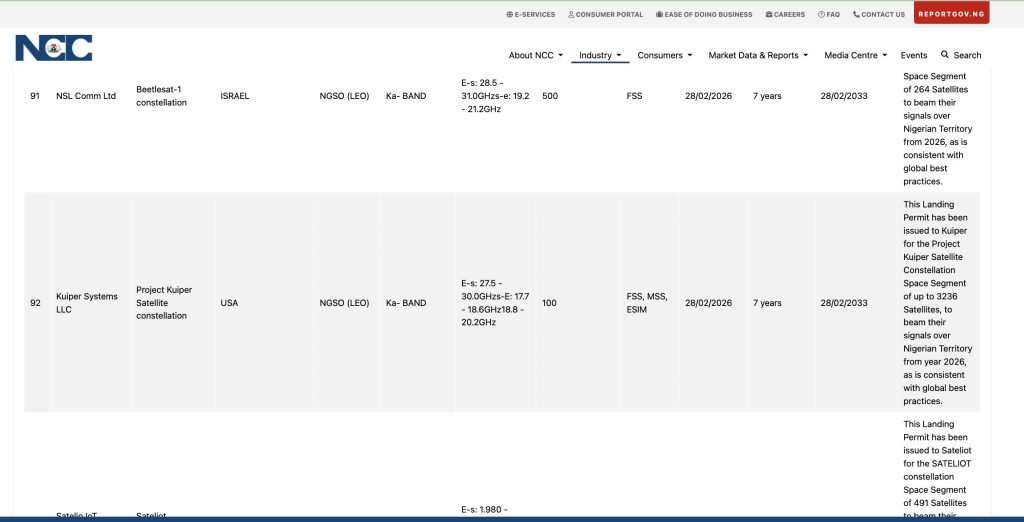

Dated February 28, 2026, the seven-year landing permit authorises Kuiper to operate its space segment in Nigeria as part of a global constellation of up to 3,236 satellites. According to the NCC, the approval aligns with global best practices and reflects Nigeria’s willingness to open its satellite communications market to next-generation broadband providers.

The permit positions Kuiper to provide satellite internet services over Nigerian territory and sets the stage for intensified competition with Starlink, currently the most visible low-Earth orbit (LEO) satellite Internet provider in the country.

The permit also gives Amazon LEO legal certainty to invest in ground infrastructure, local partnerships, and enterprise contracts, while signalling to the wider market that Nigeria is now a contested LEO battleground rather than a Starlink-led monopoly.

For regulators, telcos, and large customers, Kuiper’s approval introduces real competitive tension—one that can reshape pricing dynamics, accelerate service rollouts, and force incumbents to raise performance standards across the satellite broadband ecosystem.

When contacted for comments, a spokesperson for the Amazon team in Africa told TechCabal that they had nothing Nigeria-specific yet except what was publicly available, but would reach out when they did.

“We don’t have any information to share beyond what is publicly available at this time, but we’ll sure be in touch if we announce anything,” the spokesperson noted in a Tuesday email.

What the NCC approval covers

The landing permit enables Amazon Kuiper to offer three categories of satellite services in Nigeria: Fixed Satellite Service (FSS), Mobile Satellite Service (MSS), and Earth Stations at Sea (ESAS).

FSS enables broadband connectivity between satellites and fixed ground stations, such as homes, enterprises, telecom base stations, and government facilities. This is the core service behind satellite home internet and enterprise backhaul.

MSS, by contrast, is designed for mobility and resilience. It supports direct satellite communication with portable or handheld devices and low-power terminals, typically used for emergency communications, asset tracking, maritime safety, and connectivity in remote or hostile environments.

ESIM extends high-speed satellite broadband to moving platforms, including aircraft, ships, trains, and vehicles.

These systems rely on sophisticated antennas that can track satellites in real time while in motion, making them critical for aviation and maritime connectivity as well as logistics and transport sectors.

Together, these service categories indicate that Kuiper is not entering Nigeria as a niche rural broadband provider alone, but as a multi-segment connectivity platform targeting households, enterprises, mobility, and critical infrastructure.

Why the “super-high” frequency matters

Kuiper’s Nigerian permit covers operations in the Ka-band frequency range, also known as super-high frequency, with uplink frequencies between 27.5 and 30.0 GHz and downlink frequencies spanning 17.7–18.6 GHz and 18.8–20.2 GHz.

These bands fall squarely within the spectrum used by modern high-throughput satellite systems.

Ka-band is strategically important because it delivers far greater data capacity than older satellite frequency ranges such as C-band and Ku-band.

C-band, which operates between 4 and 8 GHz, relies on large dishes and is valued for its stability and resistance to heavy rain but offers limited bandwidth.

Ku-band, operating between 12 and 18 GHz, supports smaller dishes and higher speeds for broadband and television services, yet is more susceptible to weather-related interference.

By contrast, Ka-band operates at higher frequencies, enabling significantly higher traffic capacity and making it better suited for modern high-speed broadband services.

Higher frequencies allow wider bandwidth allocations, supporting multi-gigabit traffic capacity and dense spot-beam architectures that reuse spectrum across different regions.

For users, this translates into faster speeds and lower latency. For operators, it means a lower cost per bit at scale, making satellite broadband more competitive with terrestrial alternatives in urban and semi-urban markets.

The trade-off is that Ka-band signals are more sensitive to rain and atmospheric conditions, particularly in tropical regions like Nigeria.

However, modern LEO constellations mitigate this through adaptive modulation, power control, and intelligent routing across multiple satellites and gateways.

The significance of 100 MHz bandwidth

Kuiper’s approval includes 100 MHz of bandwidth per channel, a design choice that reflects a balance between performance and cost.

In LEO systems, wider channels deliver higher speeds but require more expensive and power-hungry user terminals.

A 100 MHz channel is well-suited to Kuiper’s target performance. Amazon has indicated that its standard customer terminal is designed to deliver speeds of up to 400 Mbps.

This bandwidth size allows reliable delivery of those speeds while keeping terminals affordable enough for mass adoption.

From a regulatory perspective, dividing the spectrum into 100 MHz channels also allows Kuiper to serve multiple users simultaneously using frequency division techniques, improving overall network efficiency.

Why Nigeria matters to Project Kuiper

Nigeria is one of Africa’s largest untapped broadband markets. With a population exceeding 200 million, rapid urbanisation, a growing digital economy, and widespread connectivity gaps—especially in rural areas—the country presents a prime opportunity for satellite broadband operators looking to bridge underserved communities.

The NCC estimates that over 23 million Nigerians live in unserved and underserved areas, and mobile broadband penetration is still at 50.58% as of November 2025.

LEO satellites are particularly attractive in markets like Nigeria because they offer low latency, unlike traditional geostationary satellites.

By orbiting much closer to Earth, Kuiper’s satellites reduce signal travel time, enabling real-time applications such as video conferencing, cloud services, online gaming, and financial trading.

For enterprises, Kuiper’s services could support telecom backhaul, oil and gas operations, mining sites, ports, logistics corridors, and remote industrial facilities where fibre deployment is costly or impractical.

Raising the stakes for Starlink

Kuiper’s entry significantly raises competitive pressure on Starlink, which has enjoyed a first-mover advantage in Nigeria. While Starlink has rapidly built brand recognition and a growing subscriber base with over 66,000 subscribers, making it the second-largest internet service subscriber, Amazon brings a different kind of competitive muscle.

Amazon officially rebranded Project Kuiper to Amazon Leo on November 13, 2025. Although the service has yet to launch commercially in any African market, the initiative has already crossed several key milestones on the continent.

One of the most significant came in late 2025, when Amazon signed a strategic partnership with Vanu, a technology company that develops wireless infrastructure solutions, to expand satellite connectivity to underserved rural communities, beginning in Southern Africa.

Amazon’s strengths lie in scale, logistics, cloud integration, and pricing power. Kuiper is expected to integrate closely with Amazon Web Services, creating opportunities for bundled connectivity and cloud services for enterprises and governments.

Competition between the two LEO giants is likely to drive improvements in service quality, pricing, and coverage. For Nigerian consumers and businesses, this could mean more choice, better reliability, and faster speeds over time.

Regulatory and market implications

The NCC’s decision to grant Kuiper a landing permit reflects Nigeria’s broader strategy to diversify its connectivity infrastructure and attract global technology investments. Satellite broadband is increasingly seen as a complement to fibre and mobile networks, rather than a replacement.

However, Kuiper’s success will still depend on local partnerships, ground infrastructure deployment, spectrum coordination, and regulatory compliance. Issues such as pricing, terminal availability, and rain-fade performance will shape adoption rates.

What is clear is that Nigeria’s satellite broadband market is entering a more competitive and mature phase.

As competition intensifies, the biggest winners may be Nigerian users, who stand to benefit from faster internet, wider coverage, and a more resilient connectivity ecosystem in the years ahead.