By Oluwabukunmi Familoye and Ikpeme Neto

Nigeria doesn’t contribute much to the global biotech industry which is estimated to be worth $833.34 billion with a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of over 7.02% by 2027, but this is beginning to change.

The impending growth of Biotech in Nigeria has been aided by the covid-19 pandemic where it has been central to the response. At the forefront of this increased attention is 54gene, a Nigerian biotech startup that has attracted $20 million in funding from Silicon Valley venture capitalists who are betting big on the yet unexplored African genome.

54 gene’s rise coinciding with the covid-19 pandemic has increased the potential for the founding of more biotech startups and an influx of more venture capital. Unlike other VC backed verticals, biotech is a highly specialized field that requires significant training, qualifications and expertise. Success here is predicated on the difficult ability to develop and commercialize research findings from the laboratory bench.

The Laboratory Bench and the Role of Government

In 2001, Nigeria approved a National biotechnology policy that led to the establishment of the National Biotechnology Development Agency (NABDA) under the aegis of the Federal Ministry of science and technology. The agency’s goal is to “promote, coordinate and set the research and development priority in biotechnology for Nigeria.

To further its mission, NABDA established twenty-five (25) bioresources centres in remote areas in Nigeria intending to discover untapped resources for biotech research and development. Between the parent agency and these centres, there isn’t much discernable research output. While the agency’s website alludes to being at the “cutting edge for the socio-economic wellbeing of the nation”, the filler ‘lorem ipsum’ text still on the agency’s website calls into question the commitment to their mission. The agency has also not been helped by its chronic underfunding and graft from its leadership. Its 2021 budget is only $8 million while its acting director-general was in 2020 arrested for allegedly misappropriating about $1 million further impairing the prospects of the agency.

A government agency on the other hand that has had significant research output is the Nigerian Institute Of Medical Research (NIMR) in Yaba, Lagos. Established in 1977, the institute has played a relatively active role in health research in Nigeria. It has a track record of research and collaboration. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, they collaborated with CCHUB to develop a digital tool to aid adherence to Tuberculosis medications. In 2019, its partnership with the Institute of Pasteur Senegal enabled them to acquire more skills in the detection of viruses using serological assays. This increased its preparedness for the COVID-19 pandemic when it struck in Nigeria in 2020.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, they partnered with LifeBank, a health logistics startup, to provide COVID-19 drive-in testing centres. In addition, they’ve developed local RNA kits to support COVID-19 testing and have ongoing work on a local Covid-19 vaccine. NIMR’s 2021 budget is only slightly better than NABDA’s at $11 million. A grossly inadequate amount for a leading research centre. For comparison, the United States government via its National Institutes of Health (NIH) spent $7 billion on biotech research alone in 2019.

Non-Governmental Research funding

The government’s chronic underfunding of its flagship biotech research agencies has created a huge gap. Attempts to plug this gap have attracted funding from several international efforts. One noteworthy initiative is the Human Hereditary and Health in Africa (H3Africa). The initiative which was established in 2010, offers different funding opportunities to aid genomic research in Africa to African scientists interested in this field from ideation to implementation. The initiative was funded by the United States National Institute of Health (NIH), the African Academy of Science, Wellcome Trust and the Alliance for Accelerating Science in Africa. African researchers can collaborate on different genomic projects and also access funding for their research. The initiative has invested $176 million in genomics research and 51 projects have been recorded across Africa with several in Nigeria.

One project that’s received H3Africa funding is The African Collaborative Center for Microbiome and Genomics Research hosted by the Institute of Human Virology, Nigeria. The centre’s objective is to “collaborate and implement high impact integrative research into discovery of biomarkers associated with cancer.”

Another H3Africa beneficiary is the African Center of Excellence for Genomics of Infectious Diseases (ACEGID). The centre which has also received over $9 million in funding from the world bank is hosted in Redeemer’s University, a private institution. It caught national and global attention when, alongside other partners, it sequenced the COVID-19 virus soon after it arrived on Nigeria’s shores. Becoming the first centre in Africa to achieve this feat and also contributing to the global understanding of the virus. Structured as a non-profit, it’s been able to attract significant support that’s enabled it to acquire high-end genomics equipment such as the NovaSeq 6000 sequencing system that costs over $1 million. 54gene, a privately funded company, is the only other outfit with this equipment in Africa. The cost of this singular equipment illustrates how expensive biotechnology research is. While these alternative funding mechanisms are laudable, the absence of local public funding handicaps the biotech market significantly and discourages private capital from participating. An OECD report demonstrates that public R&D funding is a catalytic force that encourages the private sector to plow in more resources as public funding de-risks the uncertain aspects of research. Public funds usually go towards unattractive basic science research that doesn’t have a clear path to revenue. This basic science is however foundational to further applied research that translates into drugs and devices used in humans. In the case of the U.S, >90% of the 210 new drugs approved in a six-year period were all based on publicly-funded basic science research that amounted to over $100 billion in funding from the government. The tacit understanding in the U.S is that the government funds basic research while the private sector figures out a path to commercialization.

Research commercialization, from bench to bedside

Central to human biotech research is the desire to translate findings into devices and treatments that can be used to advance the health of people. To get from research to commercial usage, however, new products and devices must undergo trials. This poses a barrier as human trials cost a fortune. The chronic underfunding of government-related biotech means they’re unable to adequately carry out human-based research. A lot of NABDA’s work is heavily tilted towards agriculture where there are less demanding requirements to bring products from research to market. This probably also accounts for why most Nigerian biotech papers and publications are related to agriculture. The Nigerian Journal of biotech which is published only twice a year features 90% agriculture-related papers. Similarly, the agency tasked with the regulation of the biotech industry, the Nigerian Biosafety Management Agency, has a heavy agriculture bias. It shares the same underfunding plight as NABDA and doesn’t appear to carry out as many activities related to human biotech as it does for agriculture. To its credit, It did, however, release a guideline on gene editing in December of 2020.

ACEGID, the university non-profit, has also seen the limitations of underfunding in the journey from bench to bedside. They successfully concluded the pre-clinical trials of a COVID-19 vaccine but have not been able to proceed to conduct human clinical trials due to a lack of funding. Nigeria, through the central bank, earmarked $1.3 million as a pharma R&D intervention fund early on in the pandemic. The government has also pledged a further $26 million to support local vaccine production. These amounts are however mere drops in the ocean compared to the amounts required to commercialize pharmaceuticals or develop a vaccine. In the case of the latter, it generally costs at least about $300 million to take a vaccine from the preclinical stage to approval.

The prohibitive expense of going from the laboratory to creating products for human use is a recognized global problem. To overcome this, many universities and research institutes have perfected the practice of technology transfers. The underlying premise of technology transfer is that researchers and the universities or institutes they work in are not well-positioned to commercialize research. The universities or research institutes thus transfer the knowledge, findings and skills in form of Intellectual property to other organizations where it is developed into a marketable product. These companies then pay the university royalties in return. In some cases, the research may be spun out into a company/ startup of its own while the university retains equity in the newly spun-out company. Many universities are able to garner significant windfalls when their spin-out companies become successful. One of such success stories is the purchase of the biotech company Inflazome by pharma giant, Roche for $449 million. The European universities that seeded Inflazome’s research received a big payday and are able to reinvest in research and education.

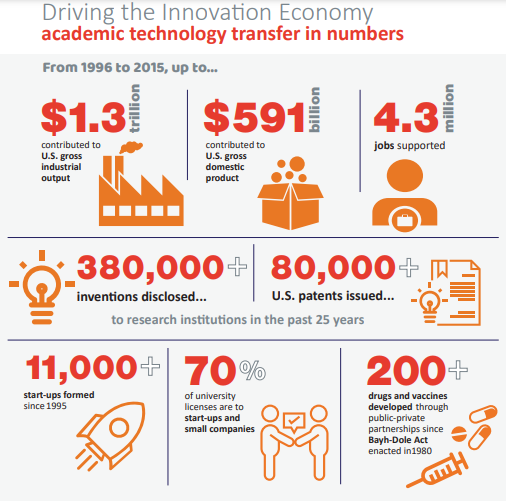

The Nigeria National Office for Technology Acquisition and Promotion (NOTAP) is the responsible agency for Tech transfers in Nigeria. According to NOTAP’s own figures, however, in the 10 years between 1999 and 2009, there were 1237 technology transfer agreements in Nigeria. Significantly, none of these agreements was in the field of biotechnology. For comparison, tech transfers in the U.S have contributed over $1.3 trillion to their gross industrial output.

Impact of tech transfers in the U.S – From AUTM.

One particular tech transfer success story in the U.S has been that of pregabalin, a drug discovered by Northwestern University on the back of a $681,000 NIH research grant that’s since gone on to earn the university over $1.4 billion in royalties.

54 gene, a biotech startup, enters the fray with this type of outsized opportunity in mind. As a for-profit outfit, 54 gene seeks to make significant commercial gains from biotech. They collect genetic materials of Africans and partner with pharmaceutical companies to develop medicines and treatments of diseases. To do this, they’re working with local researchers and created a biobank to store genetic information. They’ve also put together the African centre for translational genomics, a non-profit initiative established and bankrolled by 54gene. The ACTG exists to empower African scientists and to promote precision medicine and translational medicine.

Also coming out 54gene’s drawing board is the NCD-GHS Consortium, an initiative that has a public-private partnership the NIMR and NABDA. Together, these 3 companies are leading 2 studies that aim to recruit and gather data from 100k participants. The plan is to generate insights that could power our precision medicine and translational research objectives.

The work being done under the auspices of the NCD-GHS CONSORTIUM is funded by ACTG with support from 54gene. 23andMe, the American startup that 54gene is modelled after, has made headway in this regard. They received a $300 million investment from GSK, a global pharma leader which allowed GSK to leverage its genetic data for drug development. So far they’ve created 6 candidate drugs with one anti-cancer drug on the verge of a clinical trial. 23 and me also have another drug candidate for an inflammatory skin condition which they successfully licensed to another pharma company.

Challenges, Opportunities and interventions

Incredible opportunities abound in biotechnology that remains untapped due to the underdeveloped ecosystem and limited funding and support available for research and commercialization in Nigeria. New methods and discoveries now exist such as the revolutionary gene-editing technology CRISPR, that holds the promise of cost-effectively eliminating diseases such as the highly prevalent sickle cell disease. This development provides a real prospect for Nigeria to become globally competitive in biotechnology with less funding than was heretofore required.

With only 1% of Nigeria’s GDP allocated to science and technology, however, coupled with a tradition of misappropriation, progress remains a tall task. Private capital and startups can make a huge difference but will go much farther with government support. Were the government to increase funding and improve policy to stimulate biotech innovation, there will be a huge influx of talent and further private funding. China went through a similar transformation with many government-led reforms that propelled its biotech sector to become globally competitive second only to the U.S.

Significant investment by the government in Research centres and Universities to enable the exploration of opportunities in biotech technology transfer is a key intervention that must happen. Industry and University collaborations will inevitably arise when this happens. They will foster a change from the “Publish or perish” mindset currently prevalent in universities towards a “commercialize or crumble” mantra. Professors will become more financially successful from their research, further increasing the attractiveness of biotechnology research and increasing the influx of capable human resources into the biotech space.

Whether the government wakes up or not to this huge biotech opportunity is yet to be seen. Trust entrepreneurs, however, such as the 54 gene founders to continue to beat a path to success despite the government’s lethargy. The investors and people that support them will do well to be patient as they figure things out while also advocating for increasing government participation in the industry.