Note: The big question was “Will Spinlet and others survive the coming onslaught from Deezer, Spotify, Google Music and others?” When I say Spinlet and others, I should actually be saying Spinlet. Iroking, while not officially dead, is reportedly in zombie mode – releasing the majority of their local team. They may also not renew their content contracts, a good number of which will expire in 2014. But that’s not what we’re talking about now.]

They’re here to conquer and ride on the biggest creative wave in a generation. They’ve been called different names – Africa’s iTunes, the Music Store for Africa etc and they’ve all been launched to a lot of fanfare and music. Spinlet, Iroking and other services being created to deliver African music are vying for supremacy and the share of African wallets.

But one only has to glance over the ocean and wonder how they’ll fare when (and this is a definite when) the global players – Spotify, Deezer, Google Play and of course, iTunes – decide put boots in Africa.

The Catalogue (Or Lack of It)

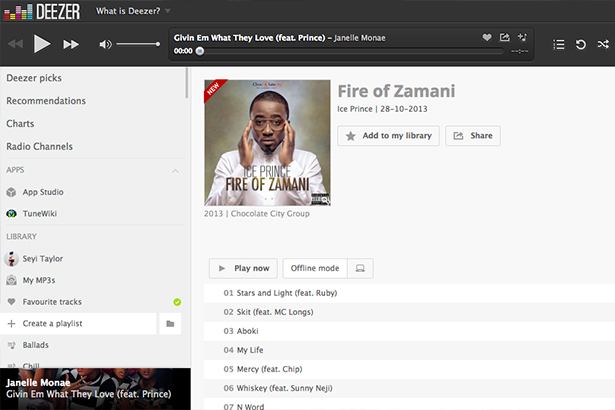

Spotify has over 20 million tracks. Deezer is the world’s largest streaming service with over 30 million tracks. Local players don’t have anything resembling this but it’s not just the catalogue size that matters, it’s also the content.

Local players focus on Nigerian music – taking advantage of an abundant supply of tracks but seem to ignore one fact. While most people enjoy local music, they often don’t listen to it exclusively. While Africans are rediscovering their sound, tastes are international and global platforms have a leg up if they can deliver a mix of music from across the world – Nigeria included.

This is already happening. When I first started using it, Deezer had a very slim Nigerian catalogue. Today, it is growing its local music collection, releasing Ice Prince’s new album the same day as Spinlet.

The Money

So, on the request of Mr Maguire:

- Spotify has raised about $288 million in venture capital and is planning to raise more

- Deezer has raised $149 million. They’ve also announced that they have 5 million paying users. The cheapest Deezer plan is $3/month. That’s at least $180 million in revenue this year alone

- Apple is only one of the most valuable companies in the world

- And Google… well, they print money for a living

While I absolutely hate using capital raised as a predictor of company success, there’s a local adage that says “it’s money they use to chase money”. Better funded companies have more resources to win the market – marketing, licensing, software development as well as throwing the kind of parties the music industry loves.

To be fair, all these businesses have an international footprint (even though Deezer doesn’t operate in America) while our local players operate, well, locally. That being said, you do wonder how much longer local firms can hold up against a business that can literally throw money at a valuable market indefinitely.

Smartphones & Data

One of the big arguments I hear for our local platforms is “Africa is different. Data is expensive so people prefer to download instead of streaming. We’ve also got feature phone apps and the global players don’t have them”.

No one is sure when smartphones will overtake feature phones in Africa but there are many signs that the end may be nearer than we imagine. Cheap Chinese Android phones are making smartphones more accessible and Nokia’s Asha is making feature phones mimic smartphones. The future isn’t here yet but it’s hurtling towards us at a thousand devices a minute. Once a large part of the addressable market is using smartphones, the feature phone “advantage” is gone. Besides, the people most likely to spend money on digital music are using smartphones anyway.

Data is getting cheaper and faster. MNOs are driving the effective price of data down by bundling more and more incentives when you buy a data bundle. Wireless providers are increasing connection speeds but not touching prices. That means that people will get more comfortable with using more data (including streaming). It also means that they’ll be able to access these apps the same way the world does.

Advantage: Spoteezer.

Shrinking Revenues

In the good old days, when an artiste released an album, Alaba would pay the artiste a large (or small) flat fee for the rights to the album. While it was not an ideal situation, some artistes got it better than others – MI Abaga reportedly walked away with N20 million from Alaba for his sophomore album – MI2: The Movie. Today, those cheques are much smaller across board due to dwindling album sales.

As a result, artistes are finding income in other places – live performances, shows, endorsements as well as mobile music (ring back tones etc). In addition, digital music is becoming a real revenue option for musicians – there’s no real limit to their earnings so it stands to reason that artistes would place their music where they can earn the most. In a realistic setting, that means the platforms with the most users. As the African Diaspora continues to play a large role in media consumption today (just ask Iroko TV), musicians should and will continue to ensure their music is on as many global platforms as possible thus reducing the advantage being experienced by local players.

All Hope is Not Lost

So are Spinlet & co on the equivalent of the Bataan Death March? I don’t think so. There are a few things that I think can create real value in those businesses, especially if they’re ready to do a few ‘weird’ things.

Help the Artistes First

The aim of every artiste is to sell as much music as possible. Your aim should be to help the players achieve this. Instead of placing the music on the company’s player (alone) and leaving the artiste to take their music to iTunes and co, become a one-stop shop for digital distribution. This seems a bit counter-intuitive but this system would mean that artistes would think of whoever did this as the defacto destination for local digital music.

There’s a new [as yet un-launched] startup called Free Me Digital that I find interesting. Instead of launching a competing music player, they’re helping artistes put their music on digital platforms the world over. That’s a bit like what CD Baby was doing. They’ve paid out about $250 million to artistes and were sold for $22 million.

Invest in back catalogues

You know what I’d really like to see on Spinlet? Fela’s entire catalogue. Now that would be worth something. I mentioned earlier that Deezer had become the biggest streaming player in the world. A lot of that was by buying back catalogues of artistes they had. This was the thing I liked the most about Gbedu FM – apart from new music, it had Nigerian music from the eighties and nineties – a much more rewarding experience.

Buy or Invest in NotJustOK.com

This one is so easy, I have no idea why no one has done it before. NotJustOk is a truly remarkable site, not just because of its traffic but because the song download data is a great predictor of what music is becoming popular and what artistes could do very well with some support. Think of it as a feeder system for the main platform. Furthermore, the ability to cross-sell music – “hey, if you like this song, you’ll like this one from Burna Boy which you can buy here” – is very interesting.

And this leads me to my final point…

Become a quasi-record label

There is no doubt in my mind that Nigeria record labels are ripe for disruption today. A less charitable mind may declare them on the ropes. Between internal squabbling and high-profile departures, Nigeria’s labels are straining under the weight of piracy and monetization issues – leaving many artistes to go it on their own. So what stops these brands from investing directly in artistes they think will do well (see why you should invest in NotJustOk?) and leveraging their digital sales platform to recoup their spend?

So what do you think? Can local players survive the coming onslaught from global music startups? Should they invest in music more directly? What do you think will happen? Please let’s know in the comments.