The news cycle in Nigeria has been dominated lately by several regulations introduced by varying financial institutions. First, the Federal Inland Revenue Service (FIRS) announced a new 5% Value Added Tax (VAT) on all online transactions from January 2020. Then the federal government unveiled plans to increase the VAT paid on all goods services to 7.5% from the current 5%. This directive is pending National Assembly approval to become law.

Finally, and like a thief in the night, the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) took everyone by surprise with a new policy with potentially far-reaching consequences.

The CBN ordered banks to impose processing fees for deposits and withdrawals on individual and corporate accounts. For individual accounts, 2% and 3% charges will apply for deposits and withdrawals above ₦500,000 respectively. Corporate accounts will attract 3% and 5% processing fees for deposits and withdrawals above ₦3m.

Implementation of the new order took effect on September 18 but is limited to seven locations in the country. This includes Lagos, Ogun, Kano, Anambra, River State, Abia and Abuja. A national rollout will kick off by March 31, 2020.

With multiple layers now added to many financial transactions, many are asking: why are all these laws coming now?

Nigeria is a broke boi

If the CBN is to be believed, the charges are meant to encourage the cashless policy it instituted a few years ago. The cashless policy was designed to reduce the circulation of physical cash in favour of digital alternatives like mobile payment and point of sale (POS) terminals.

But a closer look at Nigeria’s economy could provide more context as to why different institutions are making Nigerians pay more.

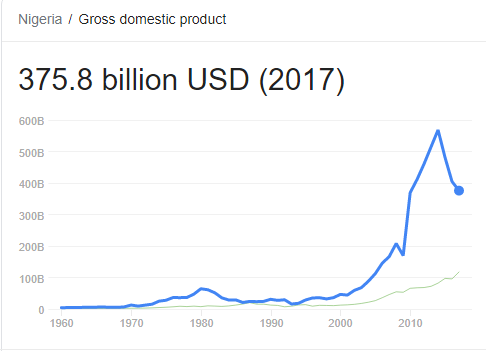

Nigeria has a serious revenue problem. Since the global oil price crash of 2014, Nigeria’s economy has been in a tailspin. It slipped into a recession in 2016. The recession ended in 2017 but Nigeria’s revenue problems continue. The economy is overly reliant on oil revenue and non-oil revenues fell in the latest government earnings, leading Nigeria to keep borrowing to stay afloat. The country presently spends almost 70 percent of its income servicing debt. Public debt has nearly doubled in four years.

And despite a GDP of $375.8 billion, taxes account for only 5%, meaning Nigeria is one of the worst tax collectors in the world.

All of these factors mean Nigeria does not have the revenue to pay its debts, considerable salaries and develop the economy. These latest regulations show a concerted effort by the Nigerian government to increase revenues one way or another. But there are concerns from analysts that although these measures may increase government revenue in the short term, they could affect consumer spending and in turn affect the overall economy.

“It is plausible that the government is seeking to extract… easy to identify areas of the Nigerian economy to shore its revenue up,” said Tunde Ajileye, an economist at risk-advisory firm SBM Intelligence. But he added that the government “should be espousing policies that support expansion of the business space and consumption to stimulate growth in the economy.”

Real life effects of these policies

The idea of the CBN policy is that it forces people to utilise digital and financial inclusion solutions like mobile money (USSD banking), agency banking and mobile apps. But according to the Punch, the charge will apply as a daily fee and will come into effect after the first ₦500,000 withdrawal each day.

It also makes little sense that the CBN has imposed charges for cash deposits. With the focus on getting people to keep money digitally, the policy “creates a negative incentive for bringing money into the banking system,” said Ajileye. He adds that “the deposit rule is counterintuitive,” and will drive people to avoid the banking system.

But the policy won’t make a significant difference in the Nigerian market, Ajileye added. With the CBN rules affecting transactions from ₦500,000, “this does not mean much as most Nigerians do not do transactions of this magnitude,” he said. A Punch editorial highlighted that only 10% of banking transactions are above ₦150,000.

Regardless, the charges could significantly impact entrepreneurs who use their personal accounts for business transactions. Of particular importance are entrepreneurs in the informal economy. Although some efforts have been made to draw this group into the regular economy by way of business name registration and tax validation, the informal economy still accounts for 60% of Nigeria’s GDP according to the IMF. With the implementation of the new charges, entrepreneurs in this sector may be forced to reduce their use of banking services and may concentrate more on traditional methods of keeping money, such as daily contributions and other schemes.

In addition to this, the CBN quietly introduced stamp duty on September 17. According to a circular from the apex bank, electronic transactions above ₦1,000 will attract ₦50 stamp duty. There is a court ruling restricting banks from collecting this fee for online transactions, but banks have ignored this order and also deny how much they collect.

Together all these measures aim to aggressively raise government revenue. But the impact on the Nigerian economy could be huge and negative.