If you do not like your neighbours – and the feeling is probably mutual – intense friction could lead to one of you calling the cops on the other. In a future where the Crime and Criminal Tracking System Bill (2019) is law, one of you could earn a record that comes back to bite really badly.

Sponsored in the House of Representatives by Hon. Simon Mwadkwon from Plateau state, the bill imagines internal security in Nigeria as a hi-tech, digitally-driven enterprise. Crime records will be digitized and in the public domain. Data to be collected and stored about offenders include offence history, fingerprints, case progress data, warrants and charges. You will be able to request a clearance and character certificate for a fee and receive it in four weeks. If you have a criminal record, then a decision will be made in eight weeks whether it is serious enough to warrant denying you the certificate.

These operations will be domiciled in a Police Central Criminal Registry, ostensibly replacing the one existing at the Force Criminal Investigation Department. All units, from the force headquarters to divisional police stations, will be connected on a secure portal. Other security agencies and embassies will be able to access information through a “Data Exchange”. Cue a jump in background checks done on visa applications and for employment verification.

It triggers an exciting picture of the future of security. The marriage of technology and security in Nigeria is long overdue according to Nnamdi Anekwe-Chive, a Lagos-based security and intelligence analyst.

“It’s going to assist law enforcement with forensic investigation and help convict the right persons and bring closure to case of violent crime”, he tells TechCabal.

A national criminal database raises the possibility of making better use of biometrics information obtained at crime scenes. The landlord that swindles tenants in Nsukka and absconds to Ogbomosho to resume operations will have a lot more to worry about.

There is a cautionary tale, though. An unsavoury reputation with data collection and privacy is bound to engender mistrust about this project, Boye Adegoke of Paradigm Initiative, a digital rights advocacy organisation, tells TechCabal. His organisation has tracked several cases of privacy violations by government agencies. The most recent was “the shameful act by the Nigerian Immigration when it displayed on social media without redacting, the international passport of a citizen who allegedly vandalized official vehicles at the Nigerian Mission in London”.

Adegoke is wary of deep, inherent problems that stand in the way of possible success. Rehabilitating the low level of trust in the judicial system is a necessary accompaniment to any technology-driven surgical makeover of national security. The bill lists the training of police officers on managing the “front-end” aspect of the system. But this ambition requires other components on the security-surveillance value chain to work optimally. That includes having officers on the streets with the right formation on where the reach of their powers end.

On the evidence of how officers indiscriminately demand access to phones and laptops, there won’t be many cheering unreservedly for the coming innovation.

“As we speak, there is no judicial oversight around how law enforcement access citizens private data”, says Adegoke. Banks, telecommunication companies and pay-day lenders are having a field day with Nigerians’ data mostly without consent. When the digitized Criminal Registry comes into being, there won’t even be a process of seeking permission.

A sign that could move the needle towards optimism would be unveiling “the consultant”. It is a designation in the bill referring to the Nigeria Police Force’s would-be partner in financing, designing, developing and installing the system. “I don’t know Richfield Technologies has such expertise”, Anekwe-Chive observes on the company mentioned in a 2015 version of the bill, “except it partners with a foreign firm with such capacity to set up a full-fledged forensic database”.

Considering the all-encompassing scope of the project being proposed “such an arrangement must be done with a verified global name otherwise we may run afoul of achieving the objective of tackling crime”. The inclusion of Richfield in the past version of the bill, without a transparent process, was a major red flag. Given the new bill is substantially the same, critics might point to that as a limiting factor against adoption.

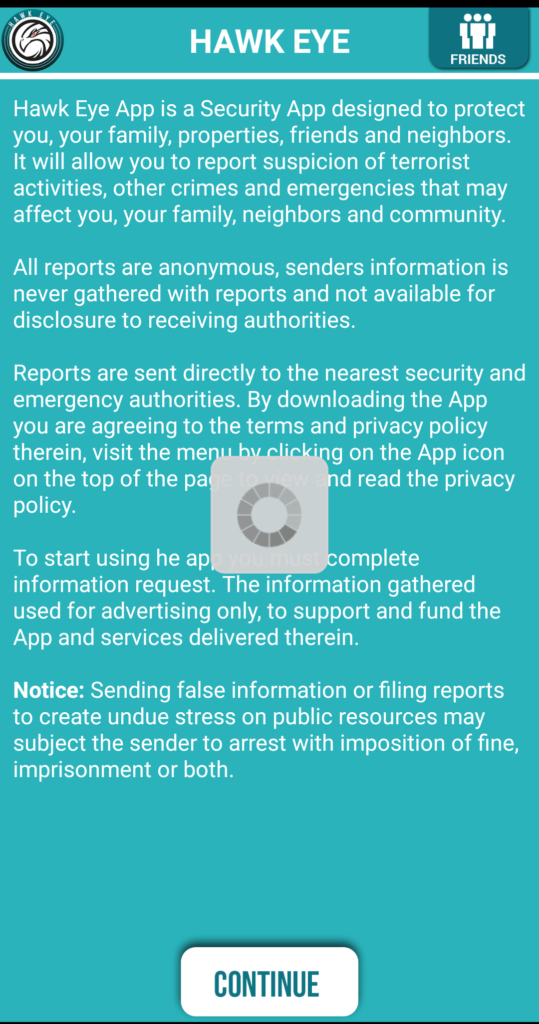

Admittedly, all of this is yet to get to concrete brick-and-mortar development. But to the extent that it is an idea with merit, the architects of the project will do well to be upfront and transparent to foster public confidence. Nigerians do not want to live in a digital dystopia, neither is there appetite for a false start that raises hopes only to quash it. Hawk Eye, the crime reporting app launched in Lagos and Abuja in 2017 has largely become defunct. At least 250 units were supplied to the Lagos state police command at the time, with the promise revolutionary security operation to come.

Before setting up a network of high-end gadgets for data collection and hosting police station data on Amazon Web Services, how about the basics? That is Paradigm Initiative’s stand, to “follow development very closely and continue to make the case for why it is inappropriate to pass the Bill in the absence of a Data protection law in Nigeria”.

Citizens, whose data and privacy are at stake, should be demanding this too.