You shouldn’t be able to text anyone in China on WhatsApp, ever.

That’s because the government blocks social media platforms like WhatsApp, Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat and Instagram.

And anything connected to Google is also off-limits: think Gmail, Google maps, the whole works.

So, how am I texting *Tunde, a Nigerian pursuing his Masters degree in China on WhatsApp this hot afternoon?

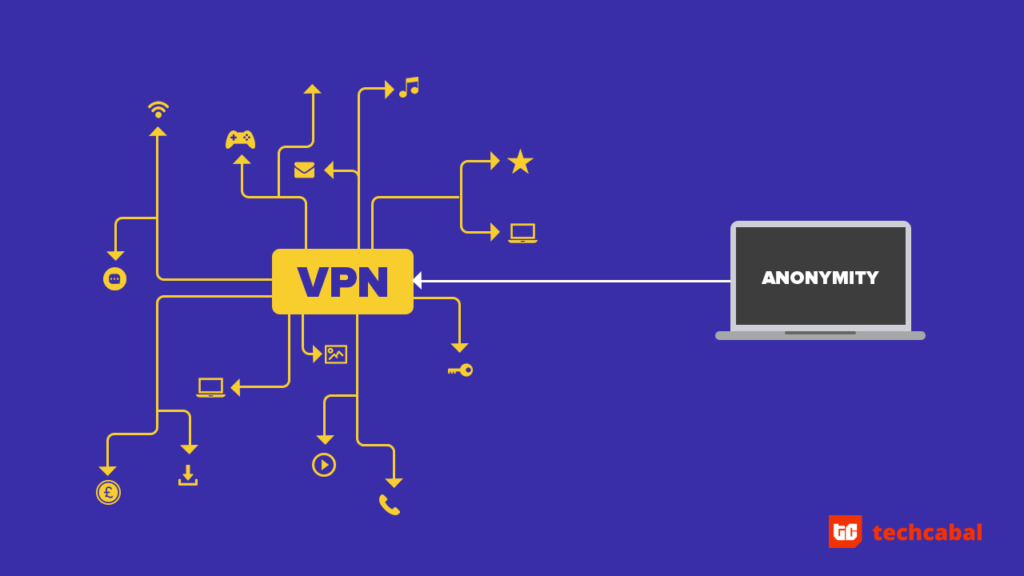

It’s the magic of Virtual Private Network (VPN). A VPN extends a private network across a public network and allows users to send and receive data across shared or public networks as if their computing devices were connected to the private network.

The summary: VPNs allow you mask your IP and access censored content.

With that out of the way, my next natural question is why anyone, knowing how restrictive China is, would still be willing to study there. Today’s popular study destinations remain Canada, the US and the UK but for Tunde, it was anything but Nigeria.

“The truth is, China wasn’t like my first choice, I wasn’t hustling to go to China. It was more about doing my Masters degree anywhere but Nigeria.”

“So, I knew beforehand of all the restrictions and other concerns. From Nigeria, I downloaded one rubbish VPN which didn’t work and I had to pay for another one when I got here.”

International students who take these freedoms for granted in their home countries often use VPNs, so I wonder why everyone else in China doesn’t do the same. But these restrictions don’t mean much to the average Chinese nationals because they have lived most of their lives under government censorship.

It also helps that the Chinese they have their version of every popular app. They have WeChat in place of WhatsApp, Weibo is their answer to Twitter, Didi in place of Uber and Baidu instead of Google.

One of the reasons the government bans apps like WhatsApp is because they allow end to end encryption. It makes it difficult for the government to spy on you.

By contrast, the government monitors WeChat conversations. Posting illegal content on the platform can get you in trouble. You can also get fined for posting job ads on WeChat.

Ten minutes into our conversation, I can only imagine how much of a technological change this has been for Tunde.

How does China compare with Nigeria in everyday digital experiences?

How digital savvy is China?

“The first thing I noticed at the airport is that all foreign nationals had to get their passports and fingerprints scanned, right from the runway. After that first check-in, then we did another immigration clearance. Now, there’s a law that you must report yourself to a police station within 24 hours. The school did this for us. They took our passports.”

“So here’s where it gets interesting. When I went to do SIM registration, all they ask for is my passport, and they scan my biodata and visa page, and they have all my info. Everything is connected from that initial registration at the airport.”

“I also had to register my accommodation at a police station. All they need is to scan your passport and your info will come out. Then they give you your police permit. If I change accommodation, I have to go to a police station again and update it or I’ll receive a fine. Now look, they have my fingerprint, my health records, my phone records, my accommodation, my school, my house permit info. All connected to my passport number.”

“One time, I needed to convert money, they had to scan my passport first, so that’s registered as a transaction I made.”

By contrast, each government agency collects its own data in Nigeria. To get a passport, you register for a National Identification Number, but to open a bank account, you go through a separate Bank Verification Number registration.

Buying a SIM card also requires another round of fingerprint scanning and photos.

With all the data collected, there is no central registry to merge data and access it. But this is hardly a pain point for most Nigerians, the data we’re likely to complain about is mobile data.

Tunde talks about his data needs while he lived in Abuja and how in hindsight, data is not a must-have in Nigeria.

“In Nigeria, my data needs were for leisure: Social media, a lot of Youtube and research for work. As much as we’re dependent on data in Nigeria, a lot of it is for self-satisfaction, at least mine was.

How much does data cost? In Nigeria, here’s what N2,000 data gets you: 4.5GB on MTN, 3.5GB on Airtel and 2GB on 9Mobile.

In China, where data is like blood, Tunde pays 40RMB per month (N2,000) for 30GB and if that is exhausted, he still has unlimited internet but at lower speeds.

“When I bought the SIM for 30RMB, I was given a 300RMB bonus. And then they deducted 40RMB to give me Internet. I currently have 208RMB left so I’m good for data for 4 or 5 months.”

“Here, I can’t go a day without data, and this is not about missing Twitter bants, it means I won’t eat.”

As the discussion moves to food, I remember a recent Twitter trend of unpopular food opinions. What does one do for food in a foreign country?

“When I first got here, I was eating rice and bread for the first two weeks. I don’t have Taobao or any of the super apps because I go to a restaurant close to my apartment that has QR codes on every table. I scan a code, pay online and they bring the food to my table.”

“At marts, I use WePay as well. Whenever I use Didi, I also pay the same way because it’s linked.”

How does he rate China and Nigeria technology-wise?

“I’ll rate them 9 because I don’t want to rate them 10. I doubt there are better tech countries. I’ll give Nigeria 3/10 and the banking sector is what contributes 2 points.”

What is daily life like?

While Nigerian public universities remain stuck in analogue, China has tech weaved into every process.

“I spend most of my time in the studio or my apartment. I wake up, head to campus and attend classes.

“In class, I need my phone to register attendance. I use WeChat for that. The module lead generates the attendance for the day’s lecture and I scan it and it records that I’m present for that class.

“There is this thing our school uses called ICE. ICE is like Facebook for school. Students and lecturers have accounts, on my dashboard, I can see all the courses I take.

“When I click on a course, I can see information like class schedule and recommended reading.

“Take one course for example. The lecturer sets assignments and uploads to ICE. I do the assignment and submit it there as well, and there’s a deadline for submission. The school already has a policy for late submission

“All your lecturer will do is mark your assignment and upload feedback. The system stores and calculates your grade according to coursework.

“The app also has a calendar that reminds you of deadlines.”

As our conversation moves to his academic work, he mentions how people take security for granted in China. According to the World Population Review, China ranks in the top 50 countries with the lowest crime rates in the world.

“There are CCTVs in every building, that one is constant. Every elevator, every lobby, every public room.

“Then you get to the streets and there’s CCTV hanging from traffic lights and street lights. And at night, it’s lights are on. And when you’re in a taxi, the cameras flash and capture the plates.”

But there’s a catch, the security crosses into government censorship. In China, the government controls everything.

What is it like to live in a repressed society?

“They don’t get unfiltered information about anything. Sometimes I watch CNN in my apartment here, it is one of the two English stations here. Anytime Hong Kong comes up on CNN, the station blacks out, the government doesn’t allow outside information at all.”

“If Trump comes on to discuss China or Hong Kong, the TV blacks out.

“The government feeds them their version of events. Many people here don’t know about the detention of the Muslim Uighurs.”

The semi-autonomous region of Hong Kong has been engulfed in pro-democracy protests that the Chinese government rejects and claims shows “signs of terrorism”.

Away from the political effects, government censorship also affects daily life.

“Before I had a VPN, these restrictions disconnected me from my relationships at home and it also makes research harder for me. I can’t use Google, and if I use Bing, all my results show in Chinese- I’ll then have to find the English version and even many of them are restricted.”

But, on the whole, Tunde seems happy and he’ll take the repression in China over coming back to Nigeria.

“Someone asked me, ‘So you’ll sacrifice some of your human rights?’ I told them even in Nigeria, human rights are reserved for a certain class of people except it’s thoroughly fought for.

“So you’re living in reality with limited rights in an environment that doesn’t help you thrive vs. limited rights in an environment you that gives you access to triumph.

“If I have to go back to Nigeria, I’ll drown in hate of the place. Besides the environment, I know how little value my profession has there so I won’t get a good-paying job.”

If you want to share your “abroad” tech experience with TechCabal, send me an email: muyiwa@bigcabal.com

*Name changed to protect identity