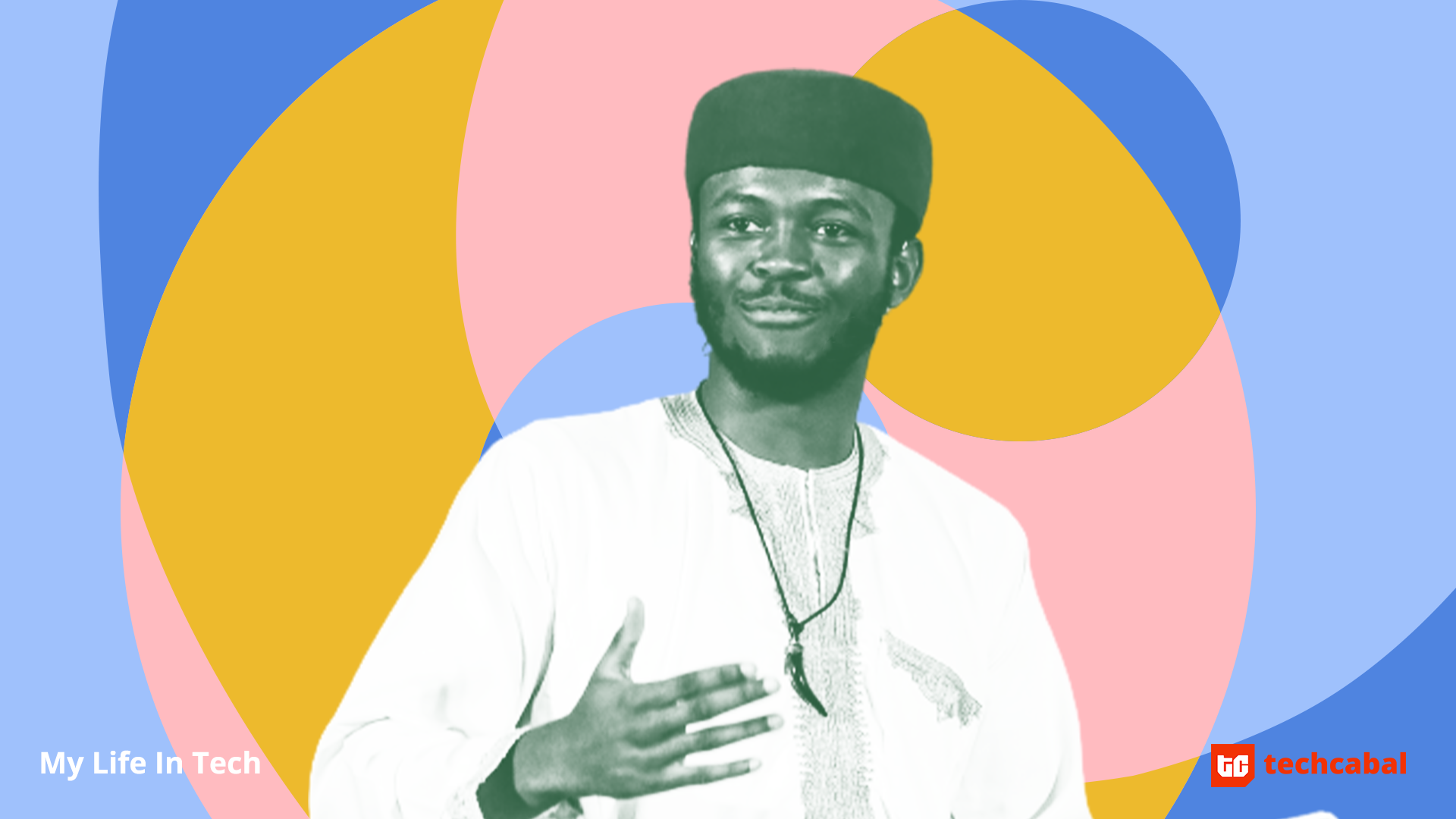

My Life In Tech is putting human faces to some of the innovative startups, investments, and policy formations driving the technology sector across Africa.

If you were to look at three different pictures of Jesse Forrester today, you will notice the same unmistakable red cap.

“It was given to me by a dear friend and for me, it has just come to represent the people that have supported me and I carry them with me wherever I’m going,” Jesse said.

“I also think it’s really cool.”

He pointed out how the hat contributes to his very pan-African life.

Jesse grew up in Nairobi, Kenya. After high school, he travelled to South Africa where he finished his A-levels at the African Leadership Academy (ALA).

His journey at ALA exposed him to several things including a wide network of pan-African thinkers.

His red cap has often gotten him mistaken as Nigerian, something he does not shy away from. But he never fails to remind people that the cap is actually from Tunisia in North Africa.

After ALA, Jesse took up a fellowship. It was his first stab at being employed and he quickly found that it was not something that he fancied.

The idea of going to university didn’t thrill him either. So he did something he’d always wanted to do – he started his own business.

Today, his company Mazi Mobility is backed by global venture builder, Satgana, and is aiming at implementing an electric vehicle ecosystem in Africa. To this end, they recently launched a new fleet of electric bodas or motorcycles.

When he speaks of Africa and the possibilities that exist in the space of e-mobility, his excitement is almost palpable.

He started his company without a university degree and he is now preparing himself to dominate the African e-mobility space.

His name is Jesse Forrester and this is his life in tech.

If you look back, you see it

Jesse grew up in Huruma flats in the Eastlands. He lived with both his parents but more time was spent with his mother.

As a child, he wanted to be a pilot but his interests varied. On some days he wanted to just sit by the television and watch a NatGeo documentary on exotic animals in the thick Amazon and on other days his PlayStation 2 was all the entertainment he needed.

There wasn’t an exact time when he decided he didn’t want to be a pilot anymore. It was just one of those things that’s there one day but slowly faded away with time – like a puddle drying in the sun.

His varying interests expanded to include his small businesses in school – selling lemonade and sweets. He also enjoyed tinkering with things – pulling them apart and putting them together.

Mazi Mobility, Jesse’s startup, is making it easier for boda riders to own and use electric vehicles that help save the planet by reducing CO emissions.

To pinpoint when in his life he got the inspiration to want a cleaner Africa, you would need to consider two things; a minister who did his job and a matatu’s smoke cloud.

In 2004, a man named John Michuki was the Minister of Transportation in Kenya. During that time, the state of buses, or matatus, in the country was terrible. These vehicles had no speed governors, seat belts and would often carry more passengers than they were supposed to.

Michuki established the ‘Michuki Rules’ which served as a game-changer for the transport sector by providing strict guidelines for matatus at the time. But one thing they inadvertently did was inspire a prepubescent Jesse.

“I actually saw a meaningful change that had a huge impact. And according to my mum, I said I wanted to become something in transport like transport minister.”

Fast forward to 2018 and Jesse was back from studying in South Africa and living in Nairobi again.

“I was walking around the city, just going on my errands, this massive matatu cuts me off and just as it’s leaving and I have a mouth full of swear words, the thing just blows a huge amount of smoke in my face.”

Set 14 years apart, these two events paved the way for the creation of Mazi Mobility but also helped inform the decisions of a young man who really cares about his environment.

“Jesse, meet Tech”

“My foray into tech really happened in secondary school, where I learned a lot about what actually makes up a game and how to actually make it,” Jesse told me over our WhatsApp call.

His introduction to tech came in the form of MIT’s Scratch Blocks. The program allowed people to develop programming skills by using blocks to code visually.

He didn’t just explore software, his tinkering came in handy when he got a chance to work with Arduino motherboards which allow people to create complex computer systems from scratch.

“I wanted to be a good engineer, that was kind of my path because it would mix hardware and software.”

Jesse’s tango with tech did not end in high school. It followed him right into ALA.

In 2017, when bitcoin was still worth only $2,000, blockchain was primarily known as the technology behind bitcoin and not much else. For Jesse, it became an interesting tool.

“I was part of a blockchain club. I was running for treasurer [in student government], and the decision was to have the elections on the blockchain.”

He would go on to win the elections and also create a project that would win his school $100,000.

The journey to Mazi by way of ALA

‘Mazi’ was not always ‘Mazi Mobility’. At one point, in the time before Jesse got into ALA, it was a photography collective – one of Jesse’s many interests.

But getting into the Africa Leadership Academy was not the smoothest ride for him.

If there’s one thing you must know, it is that Jesse Forrester sets high expectations for himself. He first heard of the Academy when he turned 12 and he knew he wanted to attend but the minimum age was 15 so he decided to wait.

At 15, he was in the middle of his high school education and decided not to apply until he was done. In his final year of high school, he finally applied.

“They waitlisted me. So I had a chip on my shoulder where I had to prove that I’ve got the leadership potential to get into the school.”

What followed was the creation of Mazi – a photography collective with a focus on creating discourse around the environment, speaking at a TEDx talk, and getting networking certifications.

And what did he do with all these things? He sent ALA an update. They needed to know that he was meant to be there.

This time they listened. He was accepted and resumed in South Africa for his 2-year course.

At ALA, Jesse was a part of the team behind “The Living Machine” a water treatment system that won them the $100,000 Zayed Sustainability Prize in 2019.

After his encounter with the smoky matatu in 2018, Jesse decided he wanted to start a company that provided electric matatus.

“I wanted to start with putting solar panels on matatus but I quickly realised that was not smart because you need like 60 of them for one matatu.”

With a few calls, he was able to connect with his co-founder and founding investor Troy Barrie.

While they discussed kicking off the business, Jesse had to leave the country briefly to present a report on The Living Machine in Abu Dhabi. During this trip, he also got a chance to interview musician and investor, Akon.

When he returned and settled down, he quit his job and focused full time on Mazi. They made plans to begin getting investors. This was March 2020.

Building Mazi through a pandemic and looking to the future

“So now we are back to running a hardware business, in Africa, in a pandemic?” Jesse laughed when he said this. It was ridiculous to even think about.

The potential investors all seemed to say the same things: “So we’re focusing on our portfolio companies right now. Let’s touch base in about a year.”

And who could blame them, 2020 was a weird year.

But he needed to raise money and to most people, Jesse just seemed crazy. While Jesse dealt with the anxiety and despair that came with 2020, he also had to get enough money to match his founding investor’s investment.

A $15,000 fund from ALA helped turn things around and in February the electric motorcycles landed in Kenya – sort of.

“The thing is, when you import something from China, especially these bikes, you have no manuals whatsoever. So we had no way of knowing what to assemble because there was a huge language barrier, so it was incredibly challenging.” Jesse said.

“I’m really happy that one of my chief engineers is a really smart guy and a biker.”

For the next month, the team would spend time figuring out the bikes and how to assemble them. They were working “from eight to eight”.

A deadline for a prototype bike was fast approaching and during our call, Jesse reminisced about what it felt like at the time.

They were just four men in his living room, trying to put an electronic boda together. It was a Saturday when they decided they were going to have to work all night to figure it out. That night, they had ugali and eggs for dinner.

By 6 am on Sunday, with none of them having slept a wink, they had built their first product, by themselves, in Jesse’s living room.

“And right now I’m really proud to say that all the bikes we have are fully assembled here in Kenya, by Kenyans. And we have the capacity to assemble – with a really small team – over 200 bikes, a month from parts all the way up. Without investment.”

“I always tell investors, ‘You guys give us X cash, you can imagine what we can do.’” he said.

I asked Jesse Forrester, as I always do with these interviews, to tell me what plans he has for the future.

“The total estimated addressable market right now stands at about $12 billion in East Africa, for electric motorbikes alone, and I say hey we want to capture a fraction of the market so I want to do over 1000 bodas by the end of next year. I want to get to over 5000 bodas by the end of 2023 with up to 200 tuktuks and 100 matatus.”

From your mouth to God’s ears, Jesse.