Among Cameroonians, new year celebrations have so far coincided with pushback against a new tax on mobile money transactions introduced by the Paul Biya administration.

From January 1, 2022, a 0.2% tax on the transfer and withdrawal of money via mobile wallets came into force, as required by the newly enacted 2022 Finance Bill signed by President Biya last November.

The tax applies to all transactions made through traceable platforms, including mobile telephony and the internet, with the exception of bank transfers and electronic transactions carried out to pay tax and customs duties.

In other words, people using money transfer platforms will incur additional fees of 0.2% when sending and 0.2% when withdrawing. That means a total of 4,000 XAF ($7) will be charged in taxes on the transfer of 1 million XAF ($1,725) between two Cameroonians.

These taxes, expected to add more liquidity to state coffers, are in addition to existing charges on mobile money transactions in Cameroon which users already complain about.

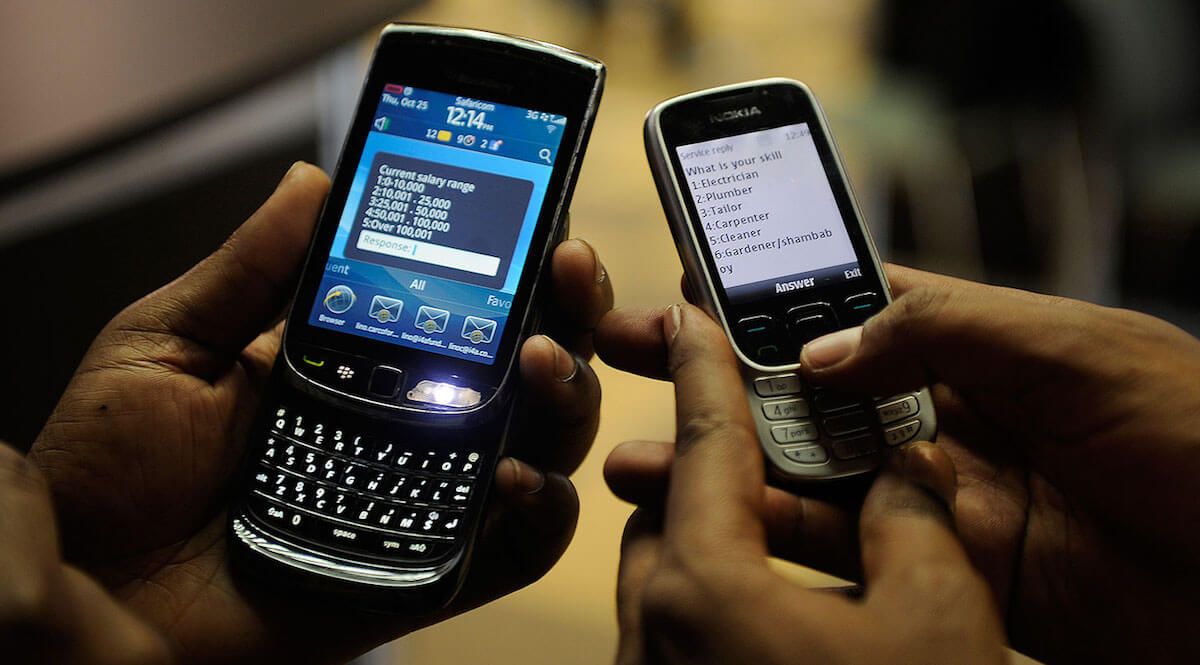

Mobile money is hugely popular among Cameroon’s 26.5 million people, particularly used by the unbanked, middle- and lower-class citizens as well as small business owners.

In Cameroon, only a third, or 35%, of adults are estimated to have bank accounts whereas mobile phone penetration has increased over the years. Network operators, led by MTN and Orange, have thus tapped into the existing mobile infrastructure to offer financial services to their subscribers.

As of 2020, Cameroon accounted for 65% (19.5 million) of the overall active mobile wallets in the CEMAC regional zone, per data from the Bank of Central African States (BEAC).

In line with growing adoption, transaction costs have increased over the past few years. To send or withdraw 100,000 XAF ($172), for instance, a user has to pay close to 2% (1,800 XAF, $3) in fees to the operator, which in turn remits part of that to the government as value-added tax.

Many Cameroonians thus consider yet another mobile money tax unfair, especially to the poorest, unbanked segments of the population, and have taken to social media to express their discontent. A trendy hashtag #endmobilemoneytax has been making the rounds on Twitter over the past week.

“Can you imagine being charged a tax to withdraw your own cash out of your account?” Rebecca Enonchong, a leader in the African tech ecosystem and one of the key voices against the new tax wrote in a tweet on January 2. “This tax is regressive and will slow financial inclusion. #EndMobileMoneyTax. #WeSayNo.”

A Douala-based entrepreneur, who asked to be anonymous, considers the tax an additional cost burden on the ordinary person in Cameroon and thinks it could discourage the use of mobile money.

“It’s essentially double taxation and means the average person will incur more cost when sending and/or withdrawing money,” she said. “The impact will be even more severe on business owners like me. I might just have to seek other options.”

Across Africa, the success of mobile money services has attracted the attention of authorities looking to expand their revenue base and new taxes are often imposed without assessing their full impact.

In countries where such taxes have been implemented, a GSMA report found that taxation was harming the uptake of mobile money services and businesses. A later study also points out that many mobile money users belong to “marginalised societal groups” hence the negative impact on financial inclusion and broader development goals of mobile money taxes is significant.

For the wider economy and government coffers, these taxes cause a contraction in mobile money transaction values and their growth trajectory reduces, with negative implications for wider corporate income and value-added taxes.

Within the region, a plan by Ghana’s finance ministry to introduce a 1.75% levy on electronic transactions in the 2022 budget is still being debated by lawmakers. That’s in addition to an earlier move to increase taxes on mobile money agents. Similarly, a 1% tax on mobile money transactions in Uganda was cut in half after protests.

Unlike Ghana’s case, however, citizens were barely informed of the details before Cameroon’s government implemented the new mobile money tax in November, according to local media reports.

The government has so far ignored the outrage, but some Cameroonians hope authorities will hear their complaints and review the decision, similar to Tanzania, where the state slashed a new mobile money tax by 30% after protests by citizens. “Knowing our government, a review of the law is all we can hope for now,” the entrepreneur said.

If you enjoyed reading this article, please share it in your WhatsApp groups and Telegram channels.