Months after it lifted its 7-month ban on Twitter, the Nigerian government has set out to regulate social media platforms with a new Code of Practice. Plans for the Code of Practice were announced in January by Director-General of NITDA, Mr Kashifu Inuwa.

Yesterday, the National Information Technology Development Agency (NITDA) announced that it had developed a draft Code of Practice for Interactive Computer Service Platforms/Internet Intermediaries—defined by the code as “electronic medium or site where services are provided by means of a computer resource and on-demand and where users create, upload, share, disseminate, modify, or access information, including websites that provide reviews, gaming Platform, online sites for conducting commercial transactions.”

According to NITDA, the draft was developed in collaboration with the Nigerian Communications Commission (NCC) and the Nigerian Broadcasting Commission (NBC), with input from platforms like Twitter, Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram, Google, and TikTok.

In the statement signed by NITDA Head of Corporate Affairs and External Relationships, Hadiza Umar, the Code is supposedly aimed at “protecting the fundamental human rights of Nigerians and non-Nigerians living in the country, as well as defining guidelines for interacting on the digital ecosystem”.

What the Code instructs

NITDA instructs that all Interactive Computer Service Platforms with more than 100,000 users would be required to fulfil certain conditions in order to operate in the country. While this includes US-based social media platforms, it also includes indigenous sites like Nairaland, blogs like Linda Ikeji, and newsletter platforms like Substack with over 100,000 users.

These platforms would have to register as legal entities with the country’s Corporate Affairs Commission (CAC), pay taxes, appoint country representatives, and more notably, “provide information to the Nigerian government on harmful accounts, troll groups, and deleting all information that violates Nigerian law”.

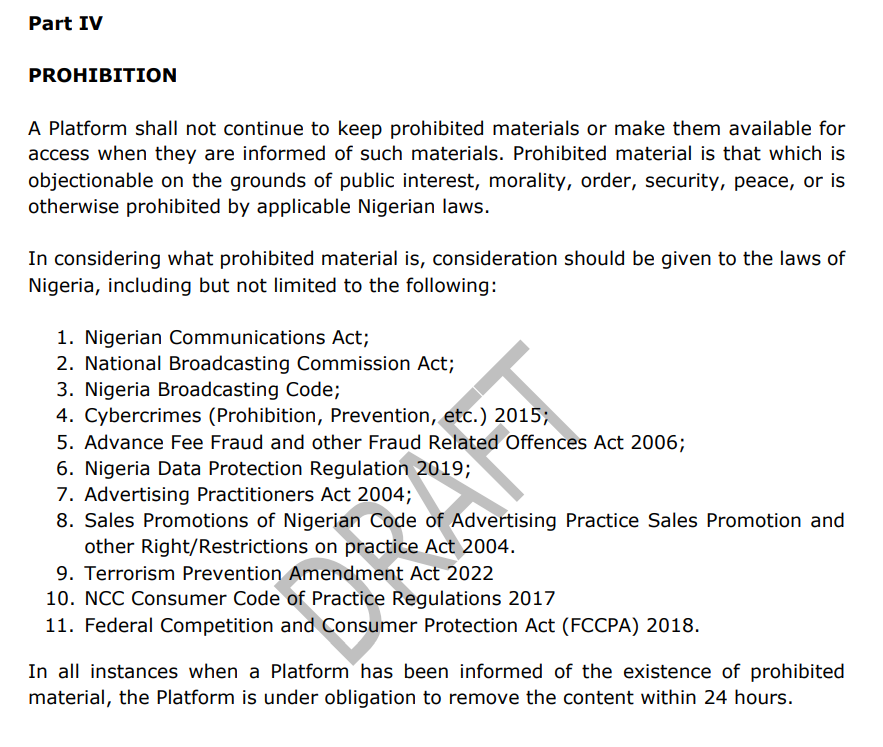

The draft Code is divided into 5 parts with the first 2 parts laying down the responsibilities of the Interactive Computer Service Platforms, while Part IV—titled “Prohibitions”—lays down orders for the removal of material prohibited by Nigerian law. According to the draft, “Prohibited Material” includes anything that threatens public interest, order, security, peace and morality—content which must be taken down within 24 hours.

In Part I of the draft Code, NITDA lays down 11 primary responsibilities which include abiding by Nigerian laws, providing dedicated channels for government agencies to lodge complaints, removing any content reported by government agencies within 24 hours, disclosing identities of reported creators to the Nigerian government, and expeditiously removing non-consensual sexual content.

Part II of the draft Code consigns 12 additional responsibilities including the requirement for Interactive Computer Service Platforms to file annual compliance reports that detail the numbers of [active] registered Nigerian users, deactivated accounts, and removed content, among other things. This part lists the responsibilities of the platforms to inform the users of their obligations which include abiding by all Nigerian laws.

Nigeria’s poor regulatory history

There are few provisions within the draft Code that fulfills NITDA’s aim of “protecting the fundamental human rights of Nigerians”. For example, Items 4 and 5 of Part I seek to protect Nigerians from promoting revenge porn and child sexual abuse materials (CSAM), while Item 1 of Part II promotes equal distribution of information for Nigerian users.

According to ‘Tooni Ajiboye, a lawyer and writer, “The good part of the bill is that it tries to hold these social media platforms accountable for all the information and mechanisms promoted on their platform. There are, however, red flags in the draft Code and they unfortunately outweigh the good.”

As Ajiboye explains it, the biggest red flag in the draft Code is how much information it wants to control. “There are about 5 classes of information highlighted: misinformation, disinformation, harmful content, unlawful content, and prohibited materials. While unlawful content already has legal backing, misinformation and harmful content are left to discretion. It’s easy to point out where child sexual abuse materials are criminalised in Nigerian law but the same can’t be said for what the draft defines as prohibited or harmful material.”

Part IV of the code, which examines Prohibited Material, prescribes that all content that is contrary to morality, or public interest should be deleted once a complaint is made. This brings to light the possibility of the Nigerian government going after citizens who post materials in support of LGBTQ persons, or anyone posting content deemed religiously “blasphemous”, a criminal offence punishable with imprisonment in many Nigerian states.

While these provisions wouldn’t constitute a problem in other regions, Nigeria’s history is riddled with fundamental human rights infringement and the misappropriation of laws. In the events following its #EndSARS protests where Nigerian youths fighting against police brutality were thrust into the global spotlight, many faced imprisonment and financial sanctions due to their involvement on and off social media.

The #EndSARS event, which also sparked commentary from celebrities like Rihanna, Trevor Noah, and ex-US president Barack Obama, spurred numerous attempts by the Nigerian government to regulate social media. There was the social media bill of 2019, and the hate speech bill which proscribed death as the penalty for hate speech. In 2021, there was also an attempt to modify the National Broadcasting Commission (NBC) Act to cover social media platforms.

Nigerians are against the bill

Since the bill was announced yesterday, many Nigerians have taken to social media, specifically Twitter, to express their concerns over the bill.

Lawyer and satirist Elnathan John said, “This is such a dangerous thing the Nigerian government is trying to do. They want to be able to track and harass citizens on social media.”

Ajiboye noted that the Code is still in its draft stage so there’s the possibility that most of its provisions would be revised. “Speaking objectively, they’re releasing the draft so they can get feedback from stakeholders and ensure that whatever is enacted is palatable to the people the Code will apply to.”

The draft Code is yet to be enacted but many Nigerians have been encouraged by Digital Africa Research Labs, an NGO studying social media misuse on the continent, to send their comments to NITDA at info@nitda.gov.ng. TechCabal has reached out to Digital Africa Research Labs for more comments but is yet to receive responses at the time of publication.

If you enjoyed this article, please share it with your networks on Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, WhatsApp, and Telegram.