How emerging economies are pioneering the technical solutions that will define the global energy transition

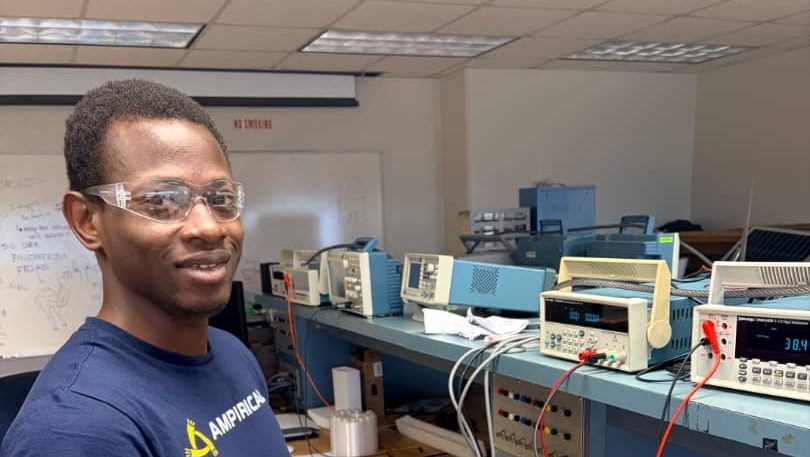

By Olaoluwa John Adeleke

When I deployed real-time monitoring systems across Nigeria’s power distribution network in 2024, I expected chaos. What I discovered instead was a masterclass in resilience engineering that the developed world desperately needs to understand.

Between May and June 2024, my research team installed Advanced Metering Infrastructure (AMI) across a distribution network in Ibadan, Nigeria, a city where voltage swings are routine, generation drops from 18,000 MW to 8,000 MW without warning, and blackouts are so common that businesses budget for diesel generators the way American companies budget for internet service. Our monitoring systems tracked voltage stability around 222.5V despite grid conditions that would trigger cascading failures in most Western grids. This wasn’t luck. It was engineering for uncertainty rather than predictability.

That research, published at IEEE SoutheastCon 2025, revealed something counterintuitive: grids designed for instability may hold the key to stable decarbonisation globally. As the world races toward net-zero targets with solar capacity reaching 3,870 GW and wind hitting 1,020 GW globally, the technical challenge isn’t simply replacing fossil fuels. It’s fundamentally redesigning how power systems maintain stability when the physics of electricity generation changes completely.

The physics problem no one’s talking about

Traditional power grids rely on rotating machinery—massive synchronous generators in coal, gas, and hydro plants that spin at precisely 60 Hz (or 50 Hz in most of the world). These spinning masses create rotational inertia, acting as shock absorbers that automatically stabilize the grid when demand suddenly spikes or generation drops. It’s elegant physics that has worked for over a century.

Renewable energy sources connected through power electronic inverters lack this physical inertia entirely. Solar panels and wind turbines convert DC to AC through solid-state electronics, not rotating machinery. When a cloud passes overhead, solar generation can drop thousands of megawatts within minutes. Wind patterns shift hour by hour. Without the stabilising inertia of traditional generators, these rapid fluctuations create frequency volatility and voltage instability that can cascade into blackouts.

This is the core engineering problem blocking deep decarbonisation: How do you build a grid that runs on sources that provide energy but not inherent stability?

The stakes are enormous. The North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC) reported that demand forecasts jumped 50% in a single year, from projections of gradual growth to scenarios involving 300+ TWh of new load from AI data centers and electrification. Utilities are making trillion-dollar infrastructure decisions while navigating unprecedented uncertainty. In PJM Interconnection, which serves 65 million people across 13 U.S. states, capacity market prices jumped from $28.92 per megawatt-day in 2024 to $329.17 in 2026—an 11-fold increase driven largely by forecast uncertainty.

Why grid instability might be our greatest teacher

My research on Nigeria’s power distribution network wasn’t meant to solve global decarbonisation. I was investigating how monitoring systems perform under extreme stress conditions. But the findings revealed something unexpected: operators who manage grids designed for unpredictability have developed adaptive strategies that conventional grid planning never needed to consider.

In developed economies, grid planning has historically worked backward from a fundamental assumption: tomorrow will look roughly like yesterday. Utilities analyse decades of historical data, project gradual changes, and build infrastructure accordingly. This approach produced remarkably reliable electricity for generations. But it optimises for accuracy in forecasting, not for resilience when forecasts fail.

Nigeria’s grid operators don’t have the luxury of predictability. Generation capacity swings wildly. Weather patterns are increasingly erratic. Economic volatility affects demand in ways that defy historical modeling. Yet somehow, millions of people and businesses keep operating. The question that fascinated me wasn’t “why does the grid fail?” but rather “how does it keep working at all?”

The answer lies in what I call “adaptive capacity architecture”—systems designed not to prevent variability, but to accommodate it gracefully. Three principles emerged from my field research:

First, monitoring systems must provide real-time visibility rather than relying on historical patterns. Our AMI deployment revealed that operators make decisions based on current conditions, not yesterday’s forecast. The IoT-enabled sensors tracked voltage, current, power factor, and energy consumption continuously, allowing operators to respond to changes as they happened rather than after they cascaded into failures.

Second, distributed resources must be orchestrated, not centralised. In regions where the central grid is unreliable, businesses and communities develop their own generation—diesel generators, solar installations, battery storage. Rather than viewing these as competitors to the grid, Nigerian operators increasingly treat them as resources that can be coordinated. My research on blockchain-based energy trading models for peer-to-peer renewable microgrids, published in the International Journal of Research in Electrical and Electronics Engineering, explored how distributed generation could be integrated into grid operations through decentralised coordination mechanisms.

Third, failure modes must degrade gracefully rather than catastrophically. The difference between a local outage and a regional blackout often comes down to whether the system can isolate problems before they propagate. Digital twin modeling—technology my team explored in research published in the International Journal of Industrial Engineering Research and Development—enables real-time simulation of how interventions will affect grid behavior, allowing operators to test solutions before implementing them physically.

The synthetic inertia revolution

If renewable energy sources don’t provide physical inertia, the solution is to engineer it digitally. This is where battery energy storage systems (BESS) become transformative—not just as energy reservoirs, but as providers of grid services that stabilise power systems.

California demonstrated this spectacularly during extreme heat events in 2024. The state’s 7.3 GW of battery storage deployed energy during evening peaks when solar generation drops and air conditioning demand surges. More importantly, these batteries provided frequency response services—injecting or absorbing power within milliseconds to maintain grid stability. During periods when California historically would have faced rolling blackouts, battery storage kept the lights on.

This wasn’t just about having extra megawatts available. It was about having resources that could respond faster than traditional generators to provide what engineers call “synthetic inertia”—digital control systems that mimic the stabilising effect of rotating machinery. My research on next-generation lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles, published in Measurement: Energy, examined how advanced battery management systems with AI-driven optimisation could provide not just transportation energy but grid stabilisation services when vehicles are parked and plugged in.

The technical challenge is substantial. Synthetic inertia requires sophisticated algorithms that sense frequency deviations and respond within milliseconds. It demands battery systems capable of thousands of charge-discharge cycles without degradation. It needs control architectures that coordinate hundreds or thousands of distributed resources as if they were a single responsive asset.

But the potential is revolutionary. Every electric vehicle becomes a mobile grid resource. Every rooftop solar installation paired with battery storage contributes to system resilience. The grid transforms from a centralised hub-and-spoke architecture into a networked system where stability emerges from the coordinated behavior of distributed resources.

Digital twins and predictive resilience

The second critical innovation enabling high-renewable grids is predictive modeling that goes beyond traditional power flow analysis. Our research on digital twin modeling for real-time monitoring and fault detection in smart substations explored how creating virtual replicas of physical grid infrastructure allows operators to test scenarios before implementing changes.

Think of it as a flight simulation for power systems. Before dispatching a technician to adjust relay settings, operators can model how that change will affect voltage profiles across the network. Before disconnecting a generator for maintenance, they can simulate whether remaining resources can maintain stability. Before integrating a new solar farm, they can test how its variability will interact with existing generation.

This capability becomes essential as renewable penetration increases. At 30% renewable generation, grid operators can manage variability using existing practices. At 70% or 80%, every decision affects system stability in ways that are difficult to predict using historical data alone. Dynamic time-domain simulation models allow operators to explore how systems will behave under conditions they’ve never experienced before.

My work developing these digital twins focused on transient stability analysis—understanding how grids respond to sudden disturbances like transmission line faults or generator trips. In low-inertia grids dominated by renewable generation, these transients can trigger oscillations that traditional dampening mechanisms can’t control. By simulating these events virtually, we can design control systems and protection schemes that maintain stability even at very high renewable penetration levels.

The global applicability of emerging market innovation

The innovations emerging from grids designed for instability aren’t just relevant to developing economies. They’re increasingly essential everywhere.

The Nordic countries, Finland, Sweden, Norway, and Denmark, have achieved some of the world’s highest renewable penetration rates by embracing flexible grid architectures. Denmark regularly generates more than 100% of its electricity demand from wind, exporting excess power to neighbors and importing when the wind is calm. This works because Nordic transmission operators invested early in cross-border interconnections, real-time market mechanisms, and frequency response services from distributed resources.

Texas learned painful lessons during Winter Storm Uri in 2021, when 200+ people died and the grid came within minutes of total collapse. The state has since added substantial battery storage capacity and improved coordination between generators, but the fundamental challenge remains: ERCOT’s grid was designed assuming predictable patterns of generation and demand. When both changed simultaneously and dramatically, cascading failures nearly destroyed the system.

The contrast with California during 2024’s extreme heat events is instructive. Both systems faced unprecedented stress. Both had significant renewable generation. But California’s investments in battery storage, demand response programs, and adaptive market mechanisms allowed the grid to maintain stability. Texas’s grid, optimised for efficiency during normal conditions, proved vulnerable during extraordinary ones.

This pattern repeats globally. Australia has experienced similar challenges as coal plants retire and renewable capacity expands. Europe’s energy transition requires managing variable wind and solar across interconnected national grids with different regulatory frameworks. China, despite massive renewable build-out, struggles to integrate that capacity into existing grid infrastructure designed around coal generation.

The technical solutions pioneered in emerging markets, where unpredictability is the baseline condition rather than the exception, offer a blueprint for this transition. Not because African or South Asian grids are more advanced, but because necessity forced innovation in managing variability that developed grids are only now confronting.

Smart cities and the urban energy transition

Grid stability challenges intersect with rapid urbanisation, particularly in emerging economies where city populations are growing by millions annually. My recent research on smart cities, published in IEEE Sensors Reviews, examined how telecommunications infrastructure and advanced sensors enable integrated energy management at the urban scale.

The concept is straightforward but technically complex: cities are both major energy consumers and potential sites for distributed generation. Rooftop solar, building-integrated storage, electric vehicle charging infrastructure, and smart buildings that modulate consumption create opportunities for grid-interactive neighborhoods. When coordinated effectively, these resources can reduce peak demand, provide voltage support, and improve overall system resilience.

The enabling technologies are converging rapidly. 5G networks provide low-latency communication between grid operators and distributed resources. IoT sensors embedded throughout distribution networks provide unprecedented visibility into real-time conditions. AI algorithms optimize when to charge EV batteries, when buildings should reduce HVAC loads, and when storage systems should inject or absorb power.

My work on flexible and wearable energy storage devices, published in the Global Journal of Engineering and Technology Advances, explored how emerging nanomaterials and device architectures might enable sensor networks and edge computing infrastructure that requires no external power supply, harvesting energy from the environment. These technologies could provide the monitoring and control capabilities needed for truly adaptive grids without adding to system load.

The engineering roadmap forward

Achieving deep decarbonisation while maintaining grid stability requires integrated solutions across multiple technical domains:

Advanced forecasting and uncertainty quantification. Weather prediction for renewable generation is improving, but so is our understanding of forecast uncertainty. Rather than simply projecting how much solar or wind power will be available, next-generation forecasting provides probabilistic ranges that allow grid operators to plan for variability rather than being surprised by it.

Flexible transmission and distribution infrastructure. High-voltage DC transmission can move large amounts of power over long distances with lower losses than traditional AC systems. Dynamic line rating systems allow transmission capacity to increase when weather conditions permit. Flexible AC transmission systems (FACTS) provide real-time voltage and power flow control.

Market mechanisms that value flexibility. Capacity markets need to compensate resources for their ability to respond quickly, not just for their nameplate megawatts. Energy markets should reflect the value of power delivered when it’s most needed, not just total quantity. Ancillary services markets must compensate battery storage and demand response for the grid stabilization services they provide.

Enhanced cybersecurity and resilience. As grids become more digitally interconnected, cybersecurity becomes critical infrastructure protection. My research on biometric and RFID-based systems, published in the World Academy of Research in Science and Engineering, explored authentication mechanisms for critical control systems. But beyond preventing attacks, resilient systems must be designed to continue operating even when portions are compromised.

Workforce development and knowledge transfer. The engineers who designed and operate today’s grids learned their craft managing synchronous generation and predictable loads. Operating high-renewable grids requires new skills power electronics, real-time optimization, probabilistic forecasting, and cyber-physical system integration. Universities and utilities must collaborate to develop training programs that prepare the workforce for this transition.

Beyond technology: The human element

Throughout my research, from monitoring systems in Nigerian distribution networks to digital twin modeling for smart substations, one truth has remained constant: technology alone doesn’t ensure successful transitions. The most sophisticated algorithms and advanced equipment are worthless without operators who understand their capabilities and limitations.

This is why I’ve invested significant effort in STEM education and workforce development. My work as Program Officer with STEMintegrate focused on bridging the gap between academic training and industry needs, ensuring that young engineers understand not just the theory of power systems but the practical realities of keeping lights on while transforming infrastructure.

The energy transition happening globally is fundamentally an engineering challenge, but it’s also a human one. Communities that have lived for generations with unreliable power understandably resist changes that might make things worse. Utility workers accustomed to predictable equipment and established procedures face learning curves as new technologies are deployed. Policymakers must make decisions affecting billions in infrastructure investment based on technical projections that carry substantial uncertainty.

Success requires not just brilliant engineering but effective communication, stakeholder engagement, and patience with the inevitable setbacks that accompany any major transition.

Conclusion: The grid as living system

The power grid was once viewed as a machine with inputs and outputs, predictable behavior, and steady-state operation. As we transition to high renewable penetration, it’s becoming more useful to think of grids as living systems constantly adapting, responding to stimuli, maintaining equilibrium through feedback mechanisms rather than rigid control.

This perspective shift is profound. Machines are designed for specific operating conditions and fail when pushed beyond design limits. Living systems adapt to changing environments, sometimes in ways their creators never anticipated. The grid infrastructure being built today must embody this adaptive capacity.

My research journey from monitoring unstable distribution networks to modeling digital twins of smart substations has reinforced one central insight: the technical solutions enabling deep decarbonisation already exist. Battery storage can provide synthetic inertia. Advanced forecasting can quantify uncertainty. Digital twins can test interventions before physical implementation. Distributed resources can be orchestrated to provide grid services.

The remaining challenges are not primarily technological; they’re organisational, regulatory, and cultural. Utilities must shift from optimising for efficiency during normal conditions to prioritising resilience during extraordinary ones. Regulators need to create market structures that compensate for flexibility and adaptability, not just megawatt-hours delivered. Engineers must embrace uncertainty as a design constraint rather than a planning failure.

Africa’s grids, often dismissed as underdeveloped, are pioneering these adaptations out of necessity. The engineering principles emerging from these challenging environments offer valuable lessons for the global energy transition. Not because anyone should replicate specific technologies or approaches, but because the fundamental challenge is the same everywhere: maintaining stability while fundamentally changing the physics of how electricity is generated.

The path to deep decarbonisation runs through the engineering of adaptive, resilient power systems. The destination of a reliable grid powered entirely by clean energy is achievable. The journey requires reimagining what power systems can become.

About the Author

Olaoluwa John Adeleke is a PhD student specialising in power system studies at the University of New Orleans, where he researches grid stability, renewable energy integration, and smart grid technologies. His work has been published in IEEE conferences and peer-reviewed journals, including Measurement: Energy, IEEE Sensors Reviews, and Global Journal of Engineering and Technology Advances. He previously served as Program Officer for STEMintegrate, bridging technical education and industry workforce needs.

Connect with Olaoluwa on LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/olaoluwaadeleke/