Storing digital assets (read: cryptocurrencies) demands the same level of security-consciousness as traditional finance. Yet crypto’s promise of “sovereignty” places the burden of protection squarely on users, turning them into sole guardians of their own purses.

The digital asset industry began with non-custodial wallets, which gave users total control over their holdings without third-party interference. They simply had to hold onto their “private keys,” a string of 12–24 random words that only the user is privy to. Once they lose access to, forget, or if those keys get into the wrong hands, their crypto assets could get lost forever or wiped out.

According to CoinLedger, a global crypto tax reporting and asset tracking platform, an estimated 3–4 million Bitcoins (up to 20% of total supply) are permanently lost; that’s about $367.8 billion in value—using Bitcoin’s price as of 3:03 p.m. UTC on December 10, 2025—lost to human error, forever putting a strain on market liquidity.

It is this fragility of human memory that birthed the custodial wallet industry—where crypto exchanges hold the keys on users’ behalf—and subsequently, the hardware wallet market. Trezor Model One, created in 2014, is widely credited as the first crypto hardware wallet.

Now, Cypherock, a Singapore-headquartered company registered as “HODL Tech PTE Limited” with Indian operations, is attempting to disrupt the incumbents, Ledger and Trezor, by eliminating the single point of failure that has plagued crypto self-custody.

Founded in 2019 by Rohan Agarwal and Vipul Saini, Cypherock has sold over 15,000 crypto hardware wallets globally. Most of its customers are in the US, where the company plans to open a warehouse to ease distribution bottlenecks, as well as in Germany. Its next frontier is Africa, one of the world’s fastest-growing crypto regions, but also one of the toughest hardware markets to penetrate.

How Cypherock’s sharded wallet works

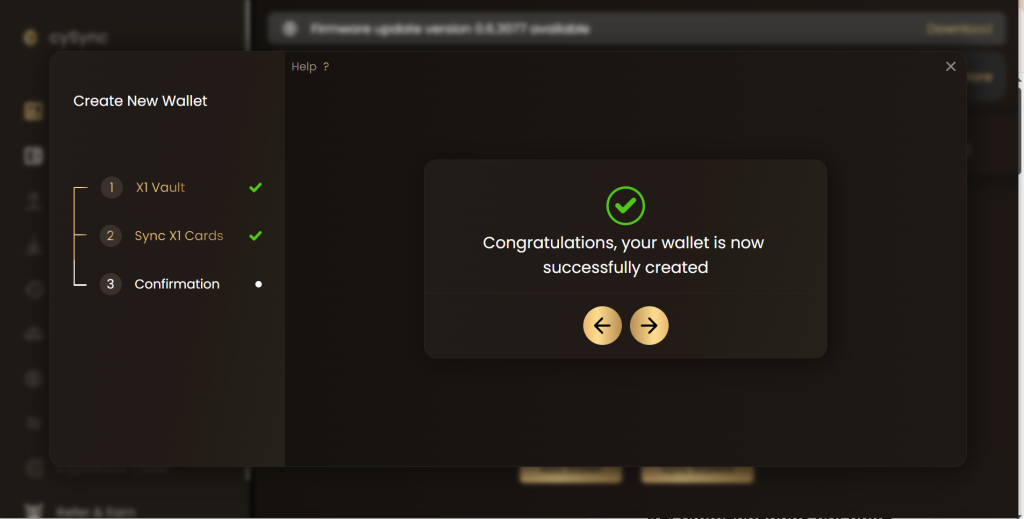

Most mainstream hardware wallets secure assets by generating a seed phrase—a private key—stored on a single chip within the device. If that device is compromised or the backup of the seed phrase is found, funds can be lost or stolen. Cypherock’s pitch is that its “sharded,” seedless design removes that conventional single‑seed failure point. The Cypherock team provided me with the “Standard” X1 wallet at no cost. The standard retail price for this model is $179, excluding delivery.

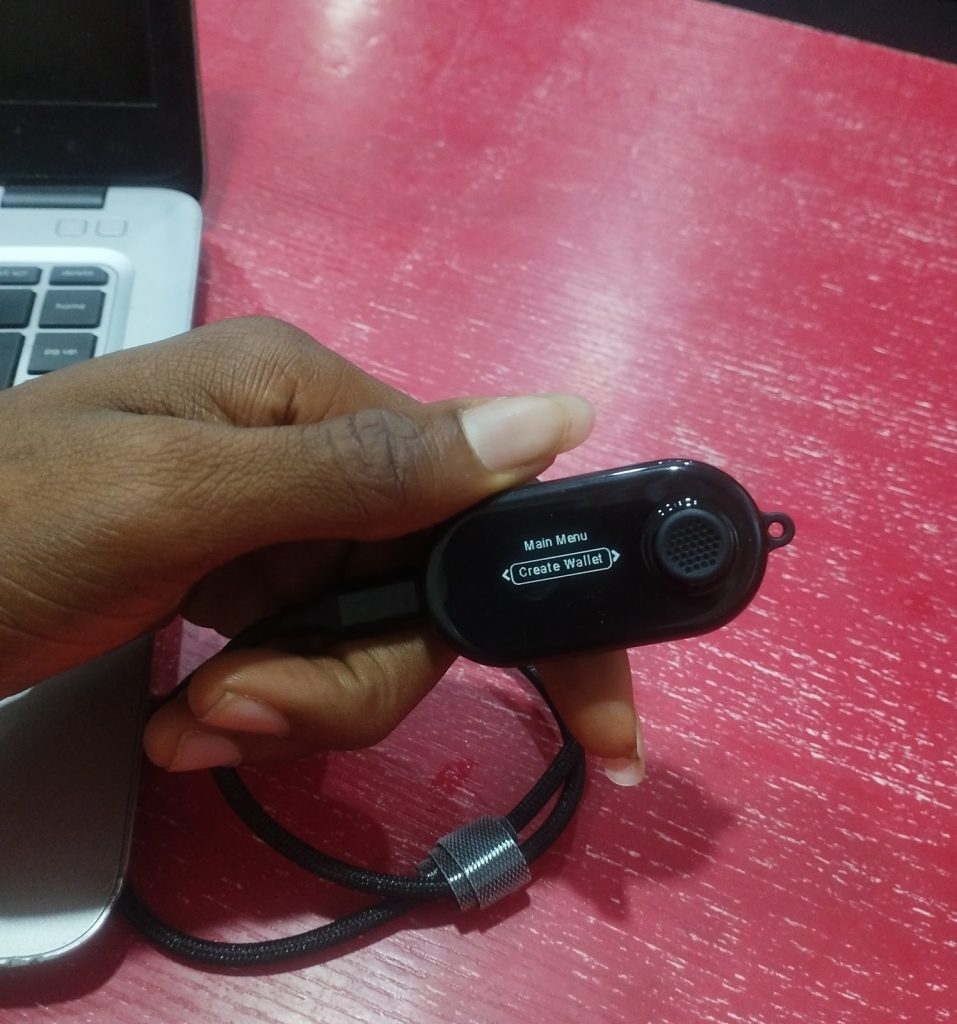

Cypherock’s X1 hardware wallet replaces that single point with five independent pieces. The wallet comes with a vault (that resembles a flash drive) and four near-field communication (NFC)-enabled smart cards. Using a cryptographic technique known as Shamir’s Secret Sharing (SSS), the private key is split into five shards, preventing a single point of failure in case a component is lost: One is stored in the X1 Vault itself, and the remaining four are embedded in the NFC-enabled cards that accompany the device.

This cryptographic algorithm allows a “secret” (the private key) to be divided into unique parts, or “shards,” where some of the parts, but not all of it, are needed to access the key. To authorise a transaction, the user would need the X1 Vault plus any one of the four cards; the full key is never stored or exposed in a single place.

“The architecture is designed so that the private key never exists in a single location effectively until the moment of transaction signing, which happens offline,” said Aditya Rawat, growth manager at Cypherock.

This “1-of-5” storage but “2-of-5” authentication model shifts the security paradigm. It mitigates the risk of a “wrench attack“—a situation where a user is physically coerced into giving up their private keys—because stealing just the Vault or just a card yields nothing.

From a cybersecurity perspective, this hardware isolation is critical. The Vault contains dual chips: an STM32L4 microcontroller and an ATECC608A secure element. Both chips generate a unique pairing key; if an unauthorised person attempts to replace or tamper with one of the chips, the device bricks itself, a feature Keylabs, a blockchain security firm, validated as a robust defence against supply chain attacks in a 2022 audit. The private key never exists in memory in full until a user deliberately initiates a transaction.

Transactions are signed offline. The moment the user taps a card on the Vault, the device reconstructs the key just long enough to authorise the action, and then dissolves it again.

Cypherock’s wallet has a built-in “1-of-4” redundancy, which means that if a user loses one card, it is inconsequential, and even the Vault on its own is useless, as access relies on the Vault and at least one of the four smart cards. The company argues that in a world where keys can be lost, stolen, compromised, or forgotten, security redundancy becomes a necessity.

Preparing for worst-case scenarios

For crypto users in emerging markets, especially those who have been burned by crypto exchanges going bankrupt, the “bus factor” matters. If a hardware wallet company disappears, users need assurance that the device does not become an unusable brick.

Cypherock has built several layers for that scenario. The X1 is compatible with BIP39, the industry standard for seed-phrase generation. The device allows users to view the full seed phrase by connecting the Vault to a power source (even a simple power bank) and tapping one card. This allows the user to transfer their crypto holdings to any external wallet of their choice. The company has also open-sourced its codebase, allowing developers to build recovery tools independent of the company’s servers, said Rawat.

“We are preparing to release an open-source mobile application that will allow users to recover their seed phrase by simply tapping two X1 cards on an NFC-enabled smartphone, bypassing the Vault entirely if the hardware is damaged or the company is defunct,” Rawat said.

For wealthy investors managing multi-generational assets, Cypherock is also pitching “Inheritance” as a marquee feature that enables a user to pass on crypto holdings as a legacy asset to their family members. By distributing the four cards to trusted family members or legal representatives, a user ensures that in the event of their death, the heirs can combine the cards to recover the funds, without any single heir having the power to drain the wallet unilaterally.

A difficult market to enter

While Cypherock’s technology is rigorous, the crypto hardware wallet market in Africa is brutal. The global market is dominated by North America and Europe, which together account for 70% of total sales, according to CoinLaw. Africa, by contrast, alongside the rest of the world, makes up a mere 10%.

Ledger and Trezor enjoy a decade-long head start and have sold a combined 9.5 million units globally. Trezor, which maintains distribution points in South Africa and Uganda, has a physical footprint on the continent. However, neither company discloses its sales figures for Africa.

Cypherock has sold over 200 units in Africa, according to Rawat. Yet the barriers to scale are twofold: economics and logistics. The X1 sells for $179 (Standard) and $99 (Basic), excluding customs and shipping costs. In countries like Nigeria, where discretionary income is lower than the cost of the device, this could be seen as a luxury product. It also competes with free, software-based self-custody wallets, like Trust Wallet and MetaMask, which Africans use.

While market size numbers are hard to come by, the revenue for South Africa’s crypto hardware wallet market is projected to grow at a compounded 26.2% yearly rate to reach $2.77 billion by 2033.

In markets where crypto is functioning as both a savings tool and a hedge, the appetite for cold storage is expected to expand.

Cypherock also sells enterprise-grade cold storage infrastructure to businesses and African crypto exchanges.

“We do both B2C and B2B. We have some major B2B partnerships that generate a huge chunk of revenue because those clients typically order in bulk—anywhere from 100 to 500 units,” said Rawat. “We also do custom branding for them. If an NFT [non-fungible token] project or a specific token community wants their own design, we customise the wallet or the cards and ship those units to them.”

However, for the last-mile consumer target demographic—crypto-native high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs) and African exchanges seeking cold storage solutions—the real friction lies in getting the product into their hands.

The distribution bottleneck

Even where demand exists, logistics can be punishing. Hardware wallets must pass through customs inspections that are often unpredictable.

Rawat explained that Cypherock’s biggest barrier in Africa isn’t awareness or adoption, but the unpredictable way hardware is treated during border inspections.

“Customs is unpredictable everywhere; Africa, the US, and even Europe,” said Rawat. “Officers sometimes open our packages during checks. They don’t tamper with the devices, but once the seal is broken, customers lose peace of mind. To solve that, we classify our product as a consumer electronic, and we’re working to place resellers or warehouses in specific countries to reduce these risks.”

Cypherock plans to establish warehouses in Africa within the next two years, contingent on when sales become significant enough to justify the investment. This would mirror its strategy in the US, where a local warehouse is being set up to ease distribution. Reducing last-mile friction, it believes, could be essential to gaining a foothold in the region.

Cypherock’s value proposition resonates mostly with sophisticated crypto users—traders, HNWIs, and family offices—rather than the mass market. Yet as Africa’s adoption grows, and as more users move from speculation to long-term storage, hardware wallets could become foundational infrastructure powering the continent’s crypto economy.