Toyosi Badejo-Okusanya was labelled stubborn as a child. Adults punished her for ignoring instructions, assuming she was being disrespectful, when in fact she could not hear.

Growing up in Nigeria, Badejo-Okusanya quickly realised that disabilities were often framed through prayer, silence or pity. Disabilities existed, but it was treated as something to be managed privately rather than accommodated publicly.

In 2017, she moved to the United Kingdom, where she encountered a different system: the National Health Service (NHS) provided hearing aids as standard care, and universities treated accessibility as a necessity rather than an inconvenience.

“Nigeria showed me how culture and stigma can shrink a person’s sense of possibility,” she said. “The UK showed me what happens when systems create room for you to exist fully and people are genuinely held accountable.”

From this contrast between cultural perception and structural support emerged Adaptive Atelier, the accessibility technology company she founded in 2023.

The startup aims to redefine how digital experiences are designed for people with disabilities across Africa, where a significant majority lack access to assistive tools.

The company works with beauty, fashion, and lifestyle brands to embed accessibility directly into websites and digital products. Many businesses are unaware of how to make their websites accessible for the 35 million Nigerians with disabilities.

In Africa, the blind spots are even more pronounced, as most products are built mobile-first and speed-first. Accessibility rarely makes it onto early product roadmaps, and when it eventually does, the focus tends to be narrow and focused on a niche or two.

Visually impaired users often get alt text for images, and deaf users get captions for videos. However, neurodivergent users and people with cognitive disabilities are often the most overlooked, as Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), dyslexia, autism, and epilepsy remain largely invisible in product design conversations. Adaptive Atelier was built to address that omission and challenge the notion that accessibility is a niche.

The adaptive ecosystem

Adaptive Atelier operates through two core products that address different parts of the accessibility ecosystem, including user experience and systemic enforcement.

AdaptiveWiz is an API based integration layer that allows users to personalise their digital experience in real time. Instead of assuming a single interface works for everyone, it enables individuals with hearing loss, epilepsy, ADHD, low vision, or other access needs to tailor how they experience a website.

Companies integrate AdaptiveWiz via a lightweight script or API into their frontend stack. Once installed, users can activate profiles that adjust visual contrast, motion reduction, layout simplification, content emphasis, and other preferences without requiring a complete redesign.

Behind the scenes, adaptations are aligned with Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) standards, a global benchmark to ensure digital content is accessible to persons with disabilities, and validated through real-world testing by disabled professionals, according to the company.

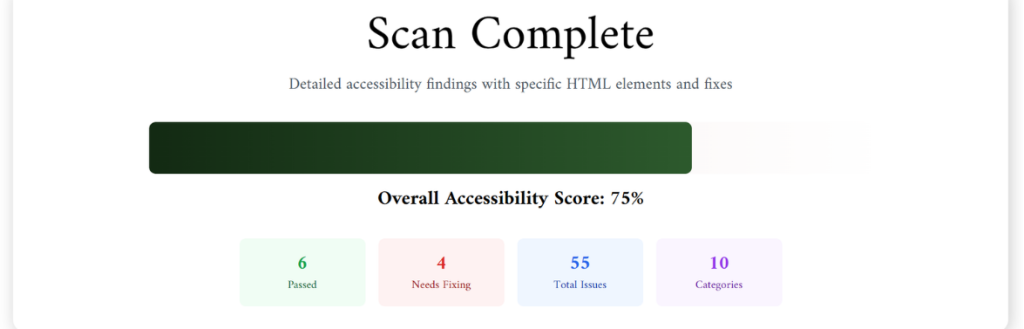

AdaptiveTest, the startup’s second core product, functions as the monitoring and diagnostics engine. It scans platforms for WCAG violations, flagging issues such as missing alt text, poor colour contrast, keyboard navigation failures, Accessible Rich Internet Applications (ARIA) misuse, and structural HTML errors.

The two products form what Badejo-Okusanya describes as an accessibility infrastructure stack that personalises digital environments and also embeds continuous oversight and human validation into platform development cycles.

Building the accessibility economy

Adaptive Atelier operates with a small core team split between Lagos and London, supported by a distributed consultant network that reflects the very community it serves. That network, the company says, includes more than 5,000 disabled professionals across multiple countries.

Since its launch, the company says it has served an estimated 5,000 users across digital audits and integrations.

The company has four streams of revenue, including B2B accessibility consulting and audits, subscription licencing for AdaptiveWiz, marketplace fees from AdaptiveTest engagements, which entail engaging disabled consultants for the platform testing, and institutional training workshops for corporate teams.

Its competitors include automated tools like Lighthouse, WAVE, and AccessiBe, which focus primarily on compliance scanning. But these automated tools, Badejo-Okusanya argued, capture only part of the problem.

“They can tell you if alt text exists, but not if it is actually useful,” she explained. “They can check colour contrast ratios, but not if a neurodivergent user finds the layout overwhelming.”

Adaptive Atelier says its differentiation lies in combining AI diagnostics with human validation in a structured format. By enabling companies to hire disabled consultants directly through its marketplace, the platform turns accessibility testing into paid professional work for the 63% of Nigerian adults with disabilities who are unemployed.

The company still faces structural challenges, as most accessibility standards are designed for Western markets and African digital environments operate under different bandwidth realities, multilingual contexts, and infrastructure constraints. However, the company says they are constantly iterating on AdaptiveWiz to work in environments with spotty internet.

Over the next five years, accessibility interfaces are expected to become more predictive with artificial intelligence. “AI is going to make accessibility scalable in ways that were impossible five years ago,” Badejo-Okusanya said, but was careful to add a condition that “only if it’s built with disabled people, not just for them.”

Adaptive Atelier combines AI tools with a network of disabled consultants to ensure lived experience remains central. As AI reshapes digital environments globally, the goal is active participation and authorship.

“The goal isn’t to build a large company,” she added. “It’s to build a scalable accessibility economy”

The girl, once labelled stubborn, is now building the infrastructure and economic pathways for disabled people that she did not see growing up, and she is doing it by demonstrating that accessibility is not charity, but the long-overdue infrastructure.