The BackEnd explores the product development process in African tech. We take you into the minds of those who conceived, designed and built the product; highlighting product uniqueness, user behaviour assumptions and challenges during the product cycle.

—

Ozumba Mbadiwe Avenue is one of the most traversed roads in Lagos, Nigeria.

It is a reliable route for commuters going from the state’s mainland environs through Victoria Island, to Lekki – the bustling town where Africa’s richest man is building a 650,000 barrels-a-day oil refinery.

Regular commuters through Ozumba are familiar with a number of picturesque sites.

There’s Civic Centre Towers, an office complex of 8,000 sqm completed in 2015 by the 88-year-old, Nigeria-based Italian construction firm Cappa and D’Alberto.

At a short distance on the same side of the road, The Wings stands tall at a similar 15 floors constructed by the same engineers. It is thrice Civic’s width, taking up 27,000 sqm.

Then there’s the aesthetically pleasing Radisson Blu, and the gigantic Oriental hotel which has now been on the market for over a year valued at ₦90 billion ($230 million).

We can argue whether the value is exaggerated, but Oriental is a showpiece of luxurious architecture, one of many in Lagos and Africa’s booming real estate market.

If you find any of this fascinating, then you would understand why Dolapo Omidire started blogging about the industry in 2014.

After completing a degree in Investment and Finance in Property from the University of Reading, he returned to Nigeria in 2013 but did not find platforms like the S&P and Real Capital Analytics that provide data on global real estate.

Fast forward to 2020 and Omidire’s blog has become Estate Intel, a B2B market research platform on African real estate. He defines it as a single source of data on commercial properties – office buildings, hotels, malls – for industry professionals.

So Google for Africa’s real estate?

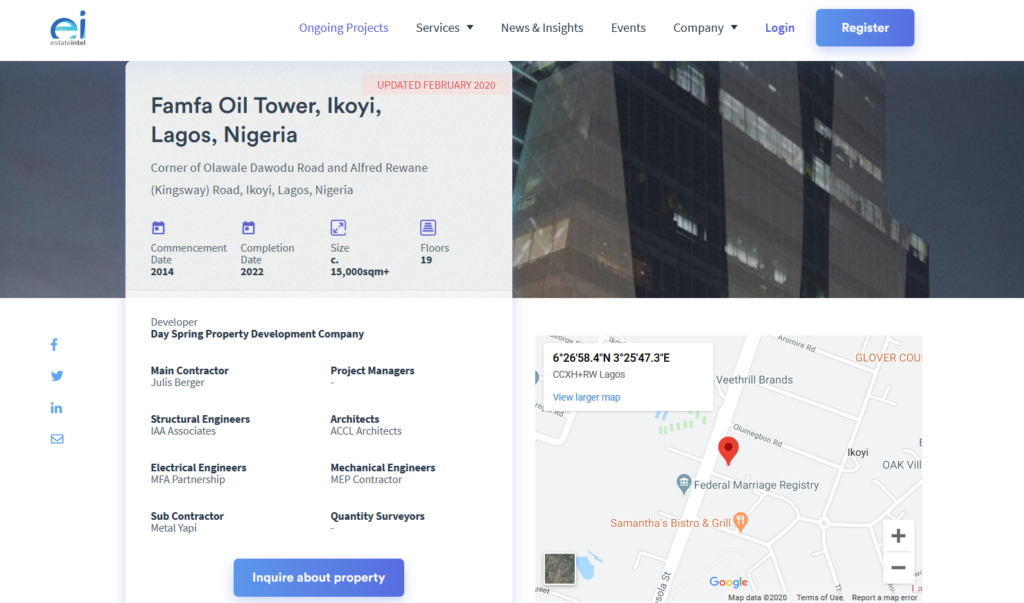

Estate Intel’s digital front office is a web application. Launched in December 2018, two months before winning a $10,000 grant at Techpoint Build, the landing page is nothing fancy or overly technical.

Omidire has never written a line of code and only recently recruited a “great designer” to fix user experience issues.

But what lies beyond the basic invitation to “get ahead in the real estate industry in Africa” is an impressive search engine linking users to data points on the most exotic construction projects in Africa.

It is not an online store or marketplace, or Uber-for-real estate. It’s the wrong place to go if your need is a residential apartment for rent or lease. For that, you may want to try Muster – Nigeria’s Airbnb-lite – or platforms like PropertyPro, though you should be aware the former isn’t cheap and the latter could break your heart.

Instead, Estate Intel is more like Google but specifically African for commercial real estate. The main differences are that unlike Google, Estate Intel’s content is not user-generated, and the majority of that content is behind a tiered paywall.

That includes granular data on the construction history, architects and building specifications for thousands of existing and ongoing construction projects in Nigeria, Ghana, Cameroon, Cote D’Ivoire and Senegal.

Who’s Estate Intel for?

Real estate is obviously a capital intensive investment. I don’t have friends who can bid for Oriental hotel.

Wings and Landmark Towers (also in Victoria Island) are occupied by oil companies and boutique brands, rather than bootstrapping startups.

Omidire’s target market is specifically companies with multimillion-dollar interests: property developers and investors. Those are the users who need historical data on how specific buildings have performed on the market and where the next hotspots are located.

Estate Intel has something called an occupier radar which tracks the tenants, documents the asking rate when a given tenant signed the lease, the floors they occupy, and other information of that sort.

On a deeper level, there are data points on the number of lifts in each building, floor-to-ceiling heights, size of the floor plane, and quality of materials used.

Then if you want to, say, compare properties on Ozumba with Independence Avenue in Greater Accra – where the $100 million Movenpick hotel is located – you could ring up Estate Intel and request a benchmark study.

Omidire says they are working on making that feature available on the web app soon, as part of a greater push to improve the company as a digital-first service provider.

Built on legwork, propelled by technology

As you may observe, Estate Intel’s core appeal is not in their tech. It is right to categorise them among an emerging crop of “proptech” startups but Omidire’s expertise is in real estate and research.

Before choosing to run the company full time as the blog started attracting clients, his day job was a real estate investment analyst.

The treasure trove of data Estate Intel now sits on is a consequence of legwork – taking many rides to African cities, knocking on doors and asking for data. In many cases, they have been turned away.

But they have won the confidence of enough property owners to boast of arguably the first digital database of commercial real estate in Africa. At present count, Estate Intel has data on 1,100 companies spanning 220,000 sqm.

The business model relies on offering subscription plans typically from 6 months to 2 years. Prices range from $600 up to $5,000. Between those ends of the scale, vendors, facility managers, developers and investors can choose packages that fit their needs.

Like Google, Estate Intel has started tapping into their potential for advertising. Equipment manufacturers and suppliers who are always looking to swoop on new developments are calling on Omidire to leverage his SEO for lead generation.

But the founder knows he’s just getting started: “There’s still so much work to be done.”

Majority of the Nigerian properties listed are based in Lagos and Abuja, but there are expanses of land in other parts of the country opening up to private equity developers.

They still have to travel to those cities to observe and capture the relevant data.

“What we are definitely trying to work on is to create a system where that information can flow to us more naturally so this process can scale better,” Omidire says.

For some potential clients, they still have to perform demos of the platform onsite. In 2019, it would usually take them about 78 days to complete a sale. This figure has improved to around 34 days in 2020, Omidire says, and they are pushing on to shorten it.

Meanwhile, they are beginning to pay attention to individual consumers who find Estate Intel intriguing but have no need to pay for subscriptions yet. Drawing from the strength of their web app’s content on land prices, they designed this Twitter bot that tells you the average land price in parts of Lagos.

Omidire admits that some of the information on Estate Intel can indeed be found on Google. But there’s a lot that’s not on Google as well and that’s their bet: that more big spenders on African real estate will value data collected and verified by groundwork, and transmitted digitally.