Regulators and banks in Africa are warming up to the idea of sharing customer data with fintech upstarts. Open banking, this new idea, is usually described by fintech experts and payment executives as game-changing because it allows greater convenience and personalisation in how banking services are delivered. But fintech and bank executives are not the only ones who plan to benefit from this new way of thinking about banking.

For the uninitiated, open banking is the fast-growing sphere of financial technology where banks and financial institutions allow third parties to access customers’ financial data through application programming interfaces (APIs).

Banking has been a historically private affair. Financial institutions typically guard their customers’ information closely. Nigeria’s Central Bank, for example, like most apex banks, expressly forbids financial institutions from disclosing customer account details to third parties without the consent of the customer.

Open banking turns this private banking relationship on its head by permitting, or in some cases like in the UK, mandating that banks give up their secrets to trusted third parties and allow them to access the account details and transaction information of their staff providing they obtain digitally authenticated customer consent.

The idea is that customers permit these third parties to sell new services to them without needing to open a new bank account with these fintechs.

This new type of transparency, finance executives claim, “benefit consumers with new insights that help people and businesses manage their money, access to products they may not have had before and new products that were not previously available.”

Boluwatife Sanwo – TechCabal Insights

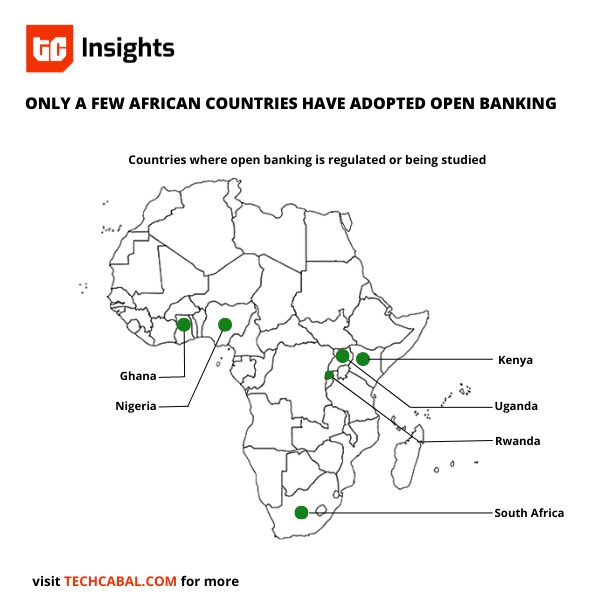

And everywhere you look online, and I assume offline, in corporate meeting rooms and offices, the benefits of this dramatic open system are loudly touted. This is the case in Europe, Latin America, and the US. In Africa, more people are taking it seriously as evidenced by new open banking guidelines and startups keen on exploring this trend.

Not very much it turns out–at least to this writer. Why? Poor data extant data systems and understated fraud risk.

Nothing new under the sun

Fraud is probably as old as finance, and in the hyper-digital world of modern finance, this well-established enemy is equally entrenched. By leveraging customers’ networked accounts, for example, open banking can help lenders get a more accurate picture of a consumer’s financial situation and risk. This is useful for building new consumer finance products. But this enterprise-wide view of customers’ financial data is precisely where immense fraud risks lie.

Open banking advocates are quick to point out that by using advanced digital tools, they are better equipped to prevent common fraud types like card fraud and that open banking itself has (so far) not spawned new types of fraud.

They are correct. Indeed open banking has not created new types of fraud. But it has created more touch points for it. In the words of Mike Haley, CEO at Cifas, a UK fraud prevention agency, “it has increased what’s known as the attack surface; the number of entry points for fraudsters to try to get into the system to initiate a payment, or to intercept personal information”.

But many banks in Africa today struggle to keep up with the demands of modern banking, to say nothing of significantly tougher technical demands of real-time systems like open banking.

Analysts at Moroccan firm, Dataprotect, say sub-Saharan African banks are particularly vulnerable to cyberattacks (bank card fraud, phishing, invasions, and so on), owing to a lack of experienced specialists and investment in cybersecurity. Some banking insiders will privately admit to how weak internal data controls are, and regulators have roundly failed to enforce better governance and tech compliance systems.

Open banking depends upon access to customer data held by banks to function effectively, but if that data is compromised or unstructured it is useless. Valuables are at the greatest risk of being lost, damaged, or stolen when they are on the move. As open banking involves increasingly large amounts of data transfer, the volume and frequency of data being shared create multiple weaknesses that can be exploited.

Open, but not enough

It is now a matter of when, not if, open banking becomes the dominant way financial services are offered. If it succeeds in its current form, open banking will be a loosely coupled payment rails held in place with APIs. But besides vague general terms that lay out in broad terms the responsibilities of banks and third parties, Nigeria’s Central Bank draft guidelines, for example, leave broad swathes of the technology compliance open to interpretation. For example, in section 2.1, Appendix II – Risk Management Standards of the draft CBN guidelines, open banking participants are asked to “use secure protocols and secure application development lifecycle.” But the CBN does not offer what constitutes a secure protocol or application development lifecycle.

The absence of standardisation may mean everyone is left to build as they see fit as long they can say, it complies with the broad provisions.

The resulting tangle will in turn make it harder for players to talk to each other and for regulators to understand how to fix the issues when they occur.

The point is not calling for more onerous rules, but for more sharing and collaboration among players. Banks do not want to be open, but since the regulator has taken this upon itself, it must go all the way. In other words, consumers alone do not have to give up data, the very businesses building open banking infrastructure will need to be open.

Since open banking prides itself on openness and sharing, it only makes sense to go all the way in being open to collaboratively fight fraud. The groups behind some of the most successful data breaches themselves operate as a collective. It is either open banking moves beyond competition or consumers and the “open banking” revolution will suffer death at the hands of the world’s enterprising and fraternal fraud corps.

Two things can be true at the same time. Open banking holds some promise for bringing financial services to more people. But Africa’s fragile banking systems are barely able to keep up with the technical requirements for serving her growing digital native population. As the system is structured now, opening multiple potential entry points for fraud will simply overwhelm banks, imperil open finance fintechs, and hurt customers.

A potential solution will involve building a culture of sharing that goes beyond customer data—the part of open banking that has commercial benefits—to the very core of the systems that will allow players to effectively fight fraud and protect consumer data.

In return, telcos are leveraging their big budgets and large infrastructure spread to channel expansion dollars and efforts towards short-term profit in Africa’s hot but tight mobile payment space.

This is not something that only guidelines will fix; regulators, banks, and fintech operators will need to roll up their sleeves to make this work. Sadly, we are still stuck at policy papers and siloed competitiveness, leaving open banking more risky than beneficial. Something has to give.

■

We’d love to hear from you

Thanks for reading The Next Wave. Subscribe here for free to get fresh perspectives on the progress of digital innovation in Africa every Sunday.

Please share today’s edition with your network on WhatsApp, Telegram and other platforms, and feel free to send a reply to let us know if you enjoyed this essay

Subscribe to our TC Daily newsletter to receive all the technology and business stories you need each weekday at 7 AM (WAT).

Follow TechCabal on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and LinkedIn to stay engaged in our real-time conversations on tech and innovation in Africa.

Abraham Augustine,

Senior Writer, TechCabal.