In the last few months, Nigerian fintechs startups have witnessed a flurry of activities that are forcing them to restrategize. From the hundred million dollar investments in rival companies to regulatory pressure, startups know they may have to tweak their approach in the new year to stay competitive.

We’re going to identify these over the coming weeks, but in this article, we’re going to focus on one interesting topic: distribution.

A tale of two companies

In January 2019, OPay and QuickTeller offered exactly the same service: payments. Both allowed people to send and receive money from anywhere in Nigeria using a network of agents. They both had digital wallets and virtual bank accounts, allowing users to make digital payments seamlessly.

However, QuickTeller offered more services than the one-year-old OPay. The ten-year-old QuickTeller offered lending services, providing users with quick loans within minutes. There was also an e-commerce service that allowed users to shop globally.

But then OPay completely tweaked its model, branching off to non-payment services in a number of sectors. It launched a bike hailing service, ORide. It delved into food delivery with OFood. It launched a ride-hailing service called OCar. It developed an investment service, OWealth. It equally launched QR code payment, an instant messaging feature and OTrike, a tricycle hailing service.

It provided huge discounts to users that helped it gain traction quickly across several states in Nigeria. A huge funding round followed and OPay has perhaps become the most talked-about tech company in Nigeria.

Regardless of how much traction its other services have gained, OPay’s main business is payments. If that’s the case it’s prudent to ask why they have launched these other ventures in the first place. Why burn cash through discounts to increase adoption of these services?

The reason is simple.

Payment isn’t exciting

The payment business seems like a pretty straightforward one. You simply allow customers to pay for things and help them receive money without any hassles. Simple, right?

But there are several startups offering these services including over a dozen banks. From Jumia to Paystack, Paga to Nairabox, Baxi Box to Remita, the payment business is highly competitive, and worse, the margins are relatively small. With many players in the market, companies constantly look for competitive angles, either through slashing prices or providing discounts.

But competing based on pricing alone is a risky bet. Speaking with TechCabal, an executive of a top Nigerian bank said that payment companies are at a disadvantage compared to banks. For instance, the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) recently slashed the cost of bank transfers, bringing it as low as N10, the same amount many fintech startups charge. All it took was for a policy directive to muscle in on one of the advantages held by startups: cheap (or free) transaction fees.

Regardless, high revenue is only possible if there is an equally high transaction volume. But how do you get high transaction volume?

Think seriously about distribution

For some companies, it is through exclusive deals. A few companies are working with the government and related agencies to process payments. Other companies are working with institutions like universities to receive school fees from students. For example, Remita, a payment service owned by SystemsSpecs, reportedly processed N1.36 trillion ($3.8 billion) for the Nigerian Federal Government when it consolidated all federal ministry and agency accounts under the Single Treasury Account (TSA) scheme in 2016.

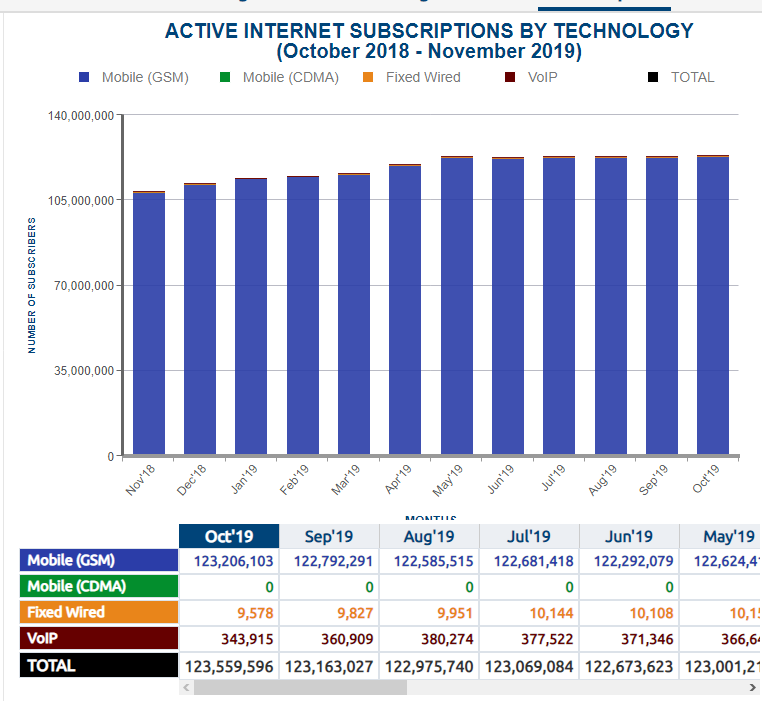

However, these are relatively small markets cornered by influential companies. Thanks to digital services, the mass market could be much bigger. The number of internet subscribers in Nigeria was 123 million in October 2019, with 72.3 million people connected to broadband internet.

So it makes sense to target the wider market. But how? On the surface, the distribution of payment services or rather how payment services can be distributed appears limited. To reach the unbanked class, companies think USSD, and to reach the urban population companies consider functional apps. Both approaches work fine even though the adoption rates have been slow compared to places like Kenya where mobile money grew big thanks to USSD.

However, the OPay model reminds us of the importance of distribution and how companies can gain traction for their services. With its numerous services, OPay provides the everyday services (food, transportation) that people need yet serves as the middleman processing all the financial transactions that happen on these services.

With thousands of subsidized bike trips per day, it is easy to see why OPay has relatively high traction. Although aggressive, expensive, unfair and probably unsustainable, the strategy has worked so far. ORide now boasts over 1,000 bike riders, putting it on par with other mobility companies like MAX and Gokada. Passengers complete ride payments using the OPay wallet, and recently most ORide bikers now reject cash payments and insist on payments from wallets. While OPay’s multiple verticals could mean more transaction volume, data to support this is not readily available.

Its $170 million funding in 2019 could allow it to attempt to grow aggressively for a few years. But when that purse dries up it will need to answer basic questions around whether it created any value at all beyond discounts.

In the meantime, its payment distribution tactic is something that many companies should try to understand and possibly replicate. But to avoid burning cash like OPay, they could attempt the same moves by partnering, merging or acquiring smaller companies relevant to their goal.