Editor’s Note: News companies are struggling to drive revenue. People aren’t paying for news, but it costs money to maintain quality newsrooms. Abubakar Idris and Olumuyiwa Olowogboyega explore how this is affecting newsrooms.

The Nigerian media landscape has always struggled to find its voice. Many mainstream media companies have built the right reach and developed loyal readership. But their revenue model is dependent on advertising. Advertising revenue has paid bills and kept their newsroom going, but it also makes them vulnerable.

A 2016 report of the Nigerian media business showed operating costs have increased. But the purchasing power of the reading public is low, discouraging many brands from putting their ads on newspaper. Alternatives like TV, radio and outdoor media had greater reach.

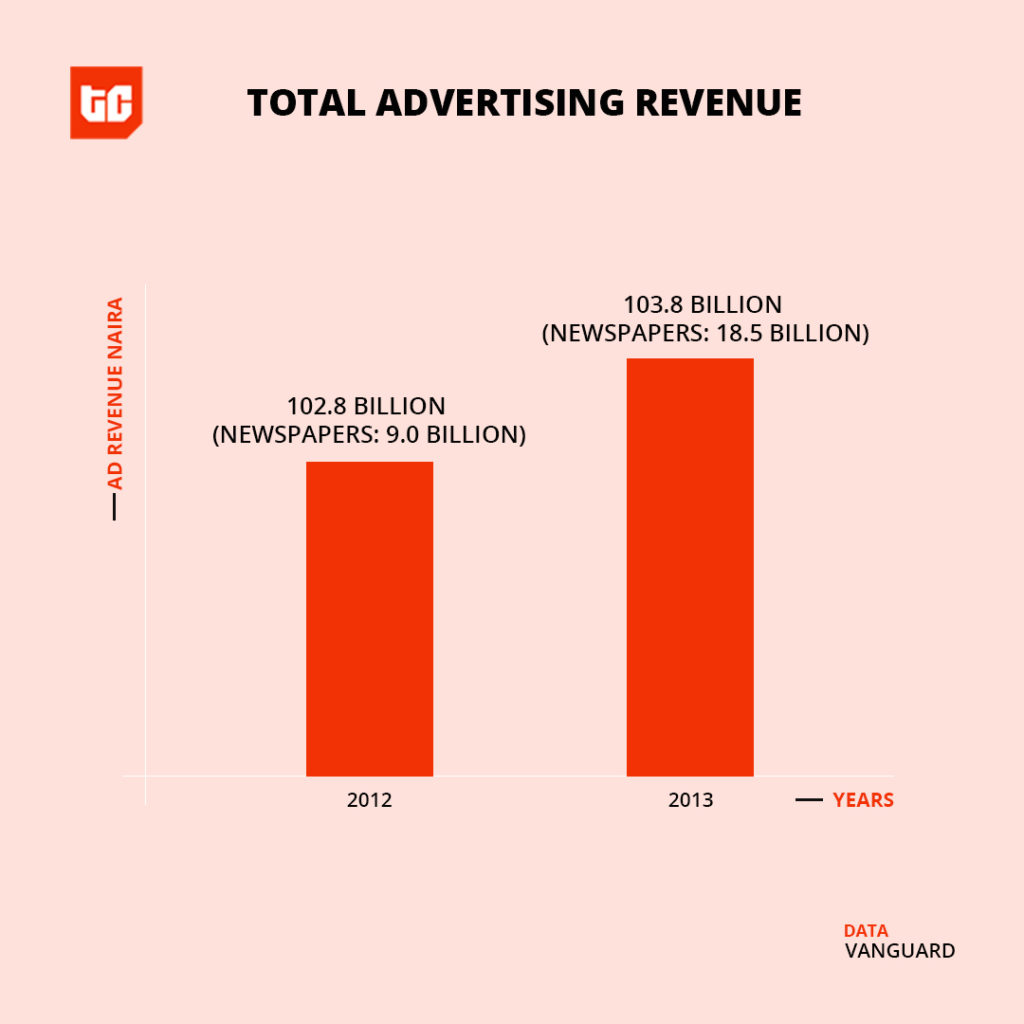

The report showed that newspaper adverts receive less than 20% of total advertising revenue in Nigeria.

But to keep ad money coming, some outlets have had to develop political affiliations and connections with companies and other interest groups. This guarantees a steady stream of revenue but at the cost of editorial independence. Advertisers could cancel a campaign and scuttle future partnerships if a media outlet publishes a report that is critical of them.

This sometimes leads to misinformation and divisive reporting. There is also the possibility that news outlets could skew reports to favour some groups.

A 2006 poll found that 75% of Nigerians believed that the government interferes with the media. Public trust in the media is low and it makes discovery of quality information about Nigeria difficult.

This problem has worsened as digital media replaces newspapers as the dominant source of information.

The Digital Pivot

With newspaper sales dropping, traditional media outlets have pivoted to digital. They are using the power of social media and their offline reputations to win over more readers.

The Guardian Newspapers in Nigeria operates two newsrooms for print and digital media, said Lolade Nwanze, former Head of Digital at Guardian Newspapers. “The kind of people you will find at the digital newsroom are younger. It is like a generational shift.”

“[But] the core business is still in print,” she said.

But with the importance of physical newspapers gone, new media publications emerged and are competing with traditional news outlets. For instance, Linda Ikeji’s Blog, originally a tabloid news website, is one of the biggest online news platforms in the country according to Alexa rankings.

Another publication, Pulse, founded in 2012 by Swiss media company, Ringier, is now one of the biggest media companies in Nigeria. It operates news platforms in Ghana and Kenya.

Another publisher, Legit, formerly Naij, has also risen to the top after eight years in operation.

Unlike traditional media companies, new media outlets focus on volume. With regular newspapers it takes 24 hours for news stories to get published. But for online publications, thousands of articles are published daily, contributing to the problem of information overload.

Many new media platforms tend to employ mostly non-trained journalists as writers and give them daily publishing targets. At Pulse, a team of under 30 writers produced around 2,000 stories per week, said a former writer who worked there. Using analytics and SEO tools, they can spot news trends and create content including social media posts and videos around them.

Traditional publishers are still on the backfoot even with their large newsrooms. Their types of news and writing styles did not appeal to readers. At this time, readers were enjoying the blog post-style of new media, rich with images and social media embeds.

With newspaper distribution dwindling, the internet improved distribution but at a cost: the information dominance of traditional outlets was gone.

“In the past, we knew all our competitors,” said Sowoolu. “[Today] you cannot name all the news outlets that exist. The landscape has changed.”

“The consumption pattern has also changed and we’re learning to take the news to people where they are,” she added.

On the internet, the competition for eyeballs is intense. Quality reporting alone does not bring in the readers. To survive on the internet, media outlets sometimes use sharp practices. Low-quality reports such as gossip and viral content have increased. Stories with clickbait headlines have increased. And public relations (PR) works, such as sponsored posts, are sometimes repackaged as news stories.

The advertising model is creating a huge problem

Unfortunately, many news publishers have been slow to develop alternative business models. Advertising continues to account for the largest part of their revenue.

In addition to adverts from Google, publishers employ their own sales teams who bring in more clients. New models like the “sponsored posts” have emerged, complementing regular ad placements like leaderboard and banner ads.

The current advertising model leaves publishers in a vulnerable position, threatening their editorial independence.

“Most people in the media space understand that [with advertising] there is definitely an implication on editorial independence,” said Preston Ideh, CEO of Stears, the Nigerian media company.

In 2008, Pulitzer Prize winner, Deji Olojede attempted to grow a quality publication while relying on advertising.

He started the news publication, NEXT Newspapers with a focus on investigative journalism. His team of over 100 writers included now famous names like Kadaria Ahmed, Tolu Ogunlesi, Molara Woods and Bayo Olupohunda, the current Editor-in-Chief at Opera News.

NEXT newspapers and 234NEXT, its online arm, published investigative stories about some of the country’s most powerful people including billionaires and the presidency. But the publication collapsed less than eight years later when their bank was allegedly pressured to pull a crucial loan deal.

He explained that the “principal chunk” of news media revenue is advertising. But the sources of that revenue “was the political and the business elites that were so infernally corrupt and which we were going after.”

“They [the bank] pulled the loan, advertisers fled and we were basically isolated,” Olojede reflected. “[T]he writing was on the wall that we could no longer sustain the enterprise.”

Meanwhile, other media companies publishing non-sensitive content still find the advertising business tough, especially on the internet.

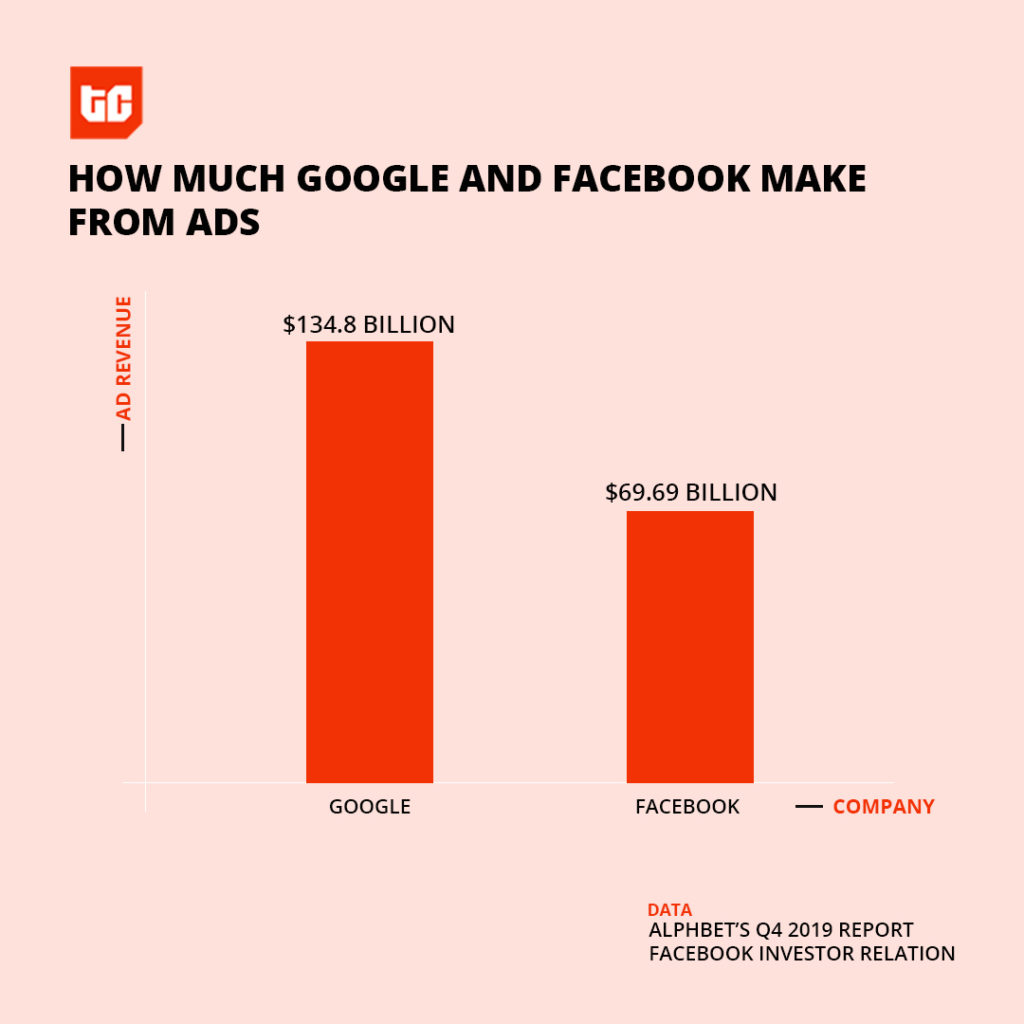

The online space is competitive and ad revenue has continued to decline. For the last five years, Facebook and Google have cornered online advertising, accounting for over 60% of revenue. Traditional news publishers are left to scramble with the fast-growing new media platforms and other low-quality publishers for the rest of the pie.

Many recently created online news media platforms have joined the bandwagon of low-quality journalism to get more eyeballs. Rather than stand out with quality content, they pursue broad audiences and try to do everything, said a 2016 report sponsored by the Omidyar Network. “[I]n the process, they undermine quality journalism by plagiarizing content, distracting attention, and undermining the audience’s trust in news media,” the report concluded.

These problems stem from many reasons. For one, most writers are underpaid by media platforms. At some publications, a single writer is required to publish a fixed number of articles per day, some as high as 20 articles. A few publications also tie writer’s paychecks to performance metrics such as the number of page views their articles gets.

For instance, in addition to an initial offer, Opera News pays writers less than $1 for every 10,000 page views their articles get, and another $5 for 100 engagements on an article.

Publications that want to do high quality news reporting are in a dilemma. They need to pay competitive salaries to journalists, produce quality stories while raking revenue from advertisers who may want to influence some editorial decisions.

Solve the revenue problem, solve the rest of the problem?

Solving news media’s revenue challenges could free them from this dilemma. But, to be clear, there are no easy solutions.

One approach is to get people to pay for news, says Mercy Abang who owns NewsWireNGR, a digital publication. “It costs a lot to get the news to readers,” she explains, “it’s only fair that these readers pay, even if it’s a token.”

“I hope we can gradually move to a time and period where consumers will pay to read a news story. It helps the newsroom file another story when someone does that,” she concluded.

How do you get people to pay for news?

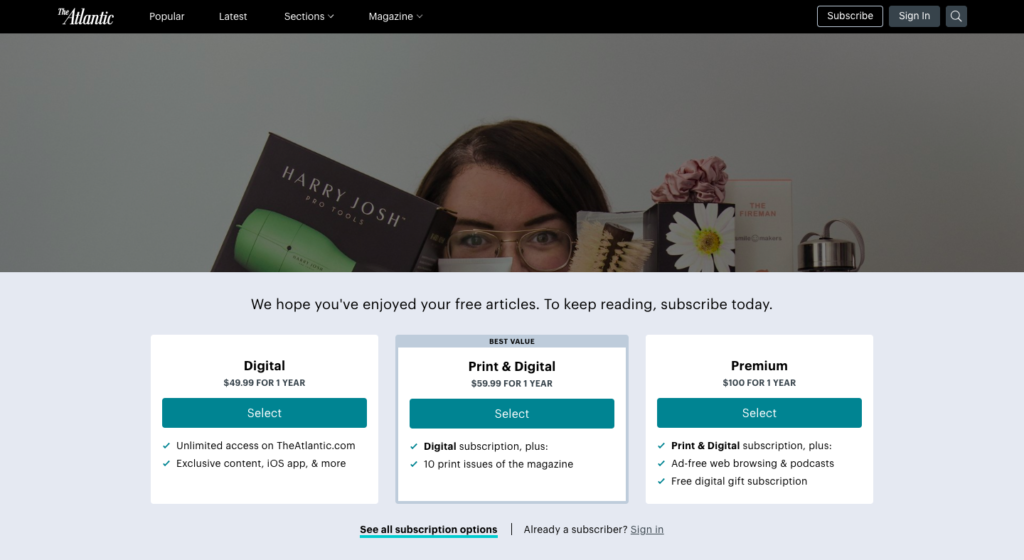

Globally, a few publications have resorted to donations and paywalls to get people to pay for news. US publications like The Atlantic, Washington Post, The New York Times, among others have switched to paywalls.

In the UK, The Guardian is one of few reputable publications without a paywall. Using different approaches, it solicits users to make donations.

But in Africa, many people are reluctant to pay for content online. On the one hand, it is due to the continent’s low purchasing power. Also, many Nigerians are hesitant to pay for content online. Combined with low literacy levels, this means people will be less willing to pay for a subscription service.

In Nigeria, Business Day is the only news publication with a paywall. Its annual plan costs ₦20,000 ($51.28) for the first year, which is more expensive than The Atlantic ($49.99), The New York Times ($26) and The Washington Post ($29).

“It was difficult to explain to people [Nigerians] why they should pay for content they read on our platform,” Linda Ochugbua, BusinessDay’s Head of Digital Marketing, said in 2019. “We had to use offline tactics in 2016 to attract subscribers.”

The publisher says 45% of its revenue now comes from subscriptions, but this includes its print subscription revenue.

Osagie Alonge, former editor-in-chief at Pulse suggests another route to get people to pay for news: publications should own their own platforms. He says media companies need to develop their own mobile apps and social platforms to retain their readers and offer more value to advertisers.

But not every publication can go this route, explains Fu’ad Lawal, Content chief at Big Cabal Media (which owns TechCabal). He explained that monetization options beyond ads are complicated by the challenging income realities in Nigeria.

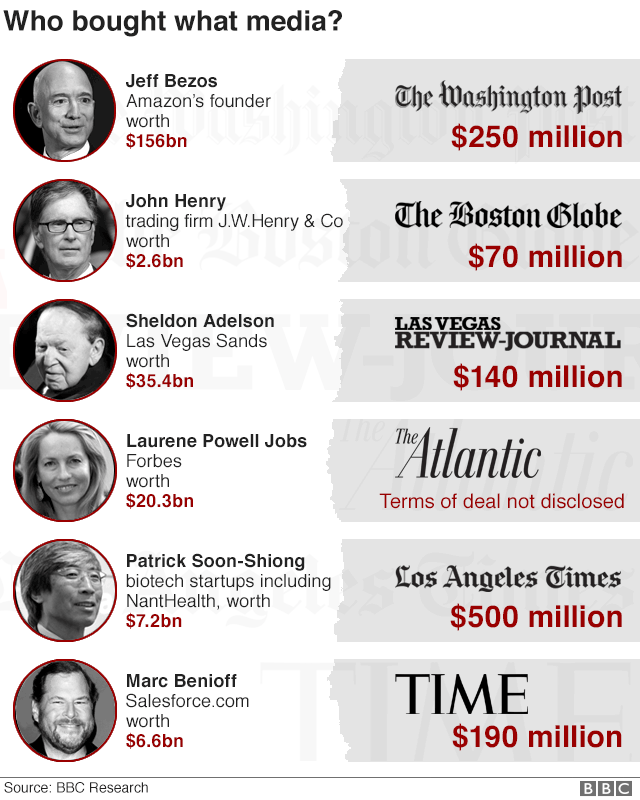

Abang shares that institutional support is becoming an important way for news publishers to win back editorial independence. Investments from wealthy individuals, impact organisations and donor funding are becoming popular routes, she explains.

This is true, especially for non-African regions like North America. Billionaires and billion-dollar funds are backing some of the biggest news publishers in these countries.

Saleforce’s co-founder, Marc Benioff owns Time Magazine, Jeff Bezos owns the Washington Post; Laurene Powell Jobs has a controlling stake in The Atlantic, Michael Bloomberg owns Bloomberg and Business Week. In China, Alibaba bought the South China Morning Post for $266 million in 2015.

Google has launched funds to support newsrooms and there are a few other funds that fund news publications in the hope of keeping good journalism alive.

Stears is one beneficiary of such impact funds. In mid-April, it secured $600,000 funding from two Nigerian investors and Luminate, an impact investor founded by the multibillion-dollar Omidyar Network.

Abang explains that “for some of these online platforms, they’ve been able to hack one or two parts of the revenue-generating game which is run to donors for support.” But she asks: “is the donor approach sustainable?”