My Life In Tech is putting human faces to some of the innovative startups, investments and policy formations driving the technology sector across Africa.

You only need spend a few minutes with Olufemi Shonubi, General Manager at EduTech, to feel the depth of his fervour to change the way Nigerians learn especially in her tertiary institutions. In this instalment of MLIT, Shonubi tells his journey to the tech industry and how EduTech is taking on-campus courses online amidst huge perception, policy and infrastructure challenges.

If you were to imagine a teenage Olufemi Shonubi, now General Manager at EduTech, a technology company taking universities online, the image of your typical male nerd may suffice. A young boy hunched over an old computer rummaging the insides for everything and nothing in particular driven by an intense hunger to understand how it works.

Hardware isn’t all there is to tech, so he also signs up to learn BASIC and becomes good enough to draw the attention of his tutors who encourage him onwards towards the endless possibilities of the technology world.

One of these possibilities comes to life in university. He begins to make a living out of assembling computers and writing programming assignments for those who can’t. Or won’t. Sometimes, for those who want, he tutors them. He works in cybercafés, public computer hubs that were popular in the 90s and early 2000s where people would assemble to use the internet on a time-based charge for good and bad purposes.

The second time, he builds something: a prototype of a spin processor, a device he needs for his dissertation and which was lacking in the department of Engineering Physics where he had obtained an undergraduate degree and was pursuing a graduate degree at the Obafemi Awolowo University in Ile-ife.

“There was no institution around that I could travel to to use one. The other option was to send my samples to South Africa to get it processed and have the results sent back to me,” says Shonubi.

“I told my supervisor I wanted to change my dissertation.”

Perhaps it was an idealistic impulse or the passion for innovation that has trailed his career in the sector over the years, but the odds were stacked against him. His supervisor thought he was insane.

But, the prototype was built. His defence was a spectacle and a constant reminder of a mentality he wishes can be completely excised from institutions on all cadres of learning: the constant resignation that “it is how things are done”.

Before joining EduTech, Shonubi had taught undergraduate students as a graduate assistant and was coming to even more realisation about the shortcomings of the educational system in the country. Classes are often one-way interactions where lecturers pour out dated lecture notes and ideas, expect same to be regurgitated by students during their examinations year in year out until a piece of paper is awarded at the end of the line as a reward for the time and resources spent. While students coast through largely unsure of their futures, lecturers stay preoccupied with the politics and bureaucracies of academia.

Taking Nigerian university campuses online

Around 2012, a call comes out of the blues. A company wanted to do a project at the Obafemi Awolowo University (OAU) and wanted to know if he was interested in being a part of the project. EduTech was exploring something that was new in the tertiary sector of academia in the country: taking university campuses online.

There are many reasons why this project was very alluring to Shonubi. Decades of underfunding and lack of quality learning material are also challenges that the tertiary education system grapples with. While it has fluctuated since 2011, the percentage of the federal government’s budget towards the education sector has steadily declined since 2016. Comparatively, in terms of output, Nigeria’s universities produce only 44% of South Africa and 32% of Egypt’s scholarly output by way of research, papers and innovation despite having nearly four times more universities than Egypt and over six times more than South Africa.

But ultimately, despite boasting of a larger number of private, public institutions, polytechnics and technical colleges, Nigeria’s institutions of higher learning can only accommodate 20% of individuals who apply each year. And hundreds of thousands of young secondary school leavers are added to this pool every year.

Here was an organisation that had identified that there was a dire need in the sector that needed to be solved and more importantly, had not taken the “it is the way things are” stance towards it.

“That excited me. I wanted to be a part of it.”

Together with the team, Shonubi designed the company’s first learning management system (LMS) which went on to support the Obafemi Awolowo University’s e-learning platform, the first of its kind in Nigeria according to Shonubi.

How did this differ from say, the National Open University established in 1983 and which had been utilising a variety of technology tools in its online distance learning endeavor?

“There is a critical component missing there and that is access to lecturers as well as access to other students on one unified platform,” says Shonubi.

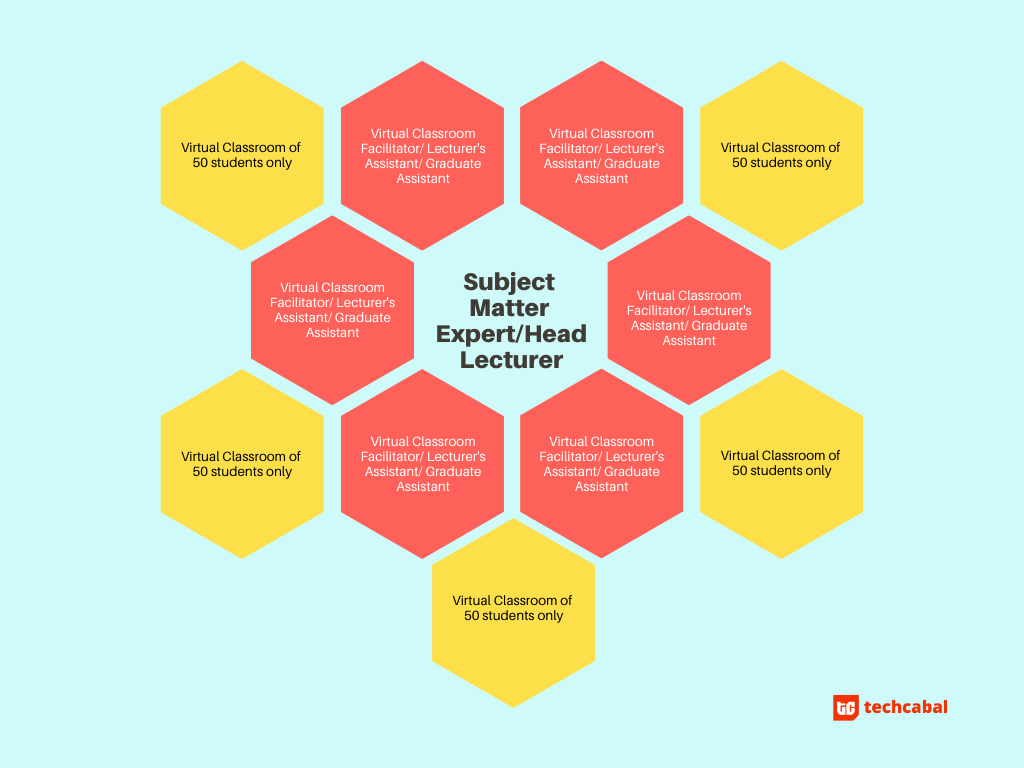

EduTech’s LMS, VigiLearn was also accompanied by Vigitab and an administrative portal and formed a virtual universe where students could receive lectures in digitised formats, interact with lecturers or facilitators (lecturer assistants) as well as among themselves.

Nonetheless, the journey to its deployment as well as subsequent ones were riddled with stumbling blocks.

What about our jobs?

Key amongst the many stumbling blocks was convincing lecturers and facilitators that the virtual learning platform was not going to take their jobs but needed them to function optimally. There was a lot of pushback, Shonubi recalls.

“In one of the meetings I had with a professor, he said, so I put my content online, students have access to it and when they have questions I have a facilitator who attends to their questions, what is stopping the university from firing me?”

Accreditations are also a sour topic. The National Universities Commission’s accreditation requirements to equate degrees and certificates obtained through virtual degree programs with their on-campus counterparts are stringent at best and outdated [Video 29:30-31:15].

OAU took about three years to obtain its accreditation, ABU, a little over two years and Babcock, another private institution which signed a partnership with EduTech in 2015 “hopefully will get accredited this year” Shonubi says.

A pandemic-induced awakening or a temporary fix?

We have followed teachers using Zoom and Google Classroom to keep their classes going. We have spoken with edtech founders who have seen massive adoption in the use of their technology tools since the lockdowns in April forced the world indoors.

But not much seemed to be going on with the institutions on the tertiary level save a handful of public and private institutions who were already adopting virtual learning platforms to some degree before the advent of the pandemic.

“Unlike before where we try to get access and send proposals and not hear anything back, now they[school administrations] are listening,” Shonubi says.

“Now, they are saying, how does this work? What would it take to get this to work for us?”

This is one area that the pandemic has opened up in conversations around virtual learning in tertiary institutions. And the company is latching onto this increased interest to spread word about the imperative of adoption of technology in education.

Thankfully, there are now success stories that it can show off. The Ahmadu Bello University (ABU) in Zaria, up north, is the second university where EduTech deployed its LMS. In the 3-4 years since its adoption, over 6,000 students are now registered across 4-5 online campus programmes and counting. The school has also deployed a distance learning hybrid where it has opened up resource centers in 6 locations across the country where students can access study materials, take assessments and register courses. Shonubi says in the near future, when adoption increases, resource centers could potentially become a service generating additional revenue for universities like ABU. Other institutions can see that it works and that there are benefits to its adoptions and will follow suit.

“It will take time, it’s not going to change overnight,” he stresses, “but the institutions on board are validating this whole process.”

He hopes that there will be a domino effect over the coming years. And regulatory changes will not be exempt. According to him, there are ongoing discussions at the National Universities Commission level about how to make fully online universities a more feasible alternative in acquiring university education.

There’s more he hopes EduTech will be able to accomplish in the future asides moving more on-campus programs virtual. How can students obtain proper internship experience as undergraduates in preparation for their careers? How can the current internship program university students undergo become more effective? How can universities adopt or optimise exchange programmes to enable the exchange of knowledge and experience across the borders of their individual institutions?

The challenges remain similar to those encountered during his dissertation as a graduate student: “this is how things are”. Skepticism and closed off mindsets towards the domestication of technologies like its virtual campus LMS remain difficult hurdles that himself and his team wake up each day to tackle, one insistution and one reluctant administrative body at a time.