“Fully digital banks like Kuda, Alat, Rubies and Vbank might claim to be solving this need but they are not reaching the unbanked. Rather they are providing alternative options for the already banked.”

On September 9, 2020, Technext, a Nigerian tech publication put out this tweet suggesting digital banks don’t meet the needs of the unbanked. So I looked at the website of two digital banks in Nigeria.

Kuda bank says it is “the bank of the free” and says it exists so you don’t have to be tied down with charges. Rubies wants to “change the world of banking and payments” by giving you a 21st century banking experience.

What is clear is that Nigeria’s digital banks are not trying to give the unbanked a platform. In November 2019, I wrote about the marketing language these banks use:

“Freedom is a common theme in their marketing language. They believe they can build profitable businesses without fees customers consider unfair.”

While financial inclusion is a concern, it is not something digital banks are equipped to solve right now. It has fallen to mobile money operators and other fintechs that offer agency banking services to try to reach people in areas where Nigeria’s biggest banks have no presence.

It’s easier for mobile money services to reach the unbanked because of the way they’re designed.

With mobile money, users only need to have feature phones and SIM cards to deposit money or make transfers.

When you think about it like that, it sounds similar to USSD. But there is one big difference; to use USSD transfers, you must first have a bank account.

That is a hard ask for people who live in remote areas where banks have no presence. It makes mobile money, with its little friction, ideal for the unbanked population.

If USSD cannot serve the unbanked population, digital banks, which need Bank Verification Numbers and Know Your Customer (KYC) processes cannot realistically serve the unbanked. Instead, digital banks serve people who already maintain bank accounts and are dissatisfied with the transaction fees and the shoddy customer experience that are the features of traditional banks.

When you define their target market this way, it should on paper, mean that everyone in Nigeria who owns a bank account is their target market. But data shows that the market is smaller.

For anyone to use a digital bank, they must have a smartphone. Right now, data puts the number of smartphone users at 10-20% of the entire population. The data holds up, when you consider that MTN, which has the largest subscriber base in the country had only 26.8 million active data subscribers in Q1 2020.

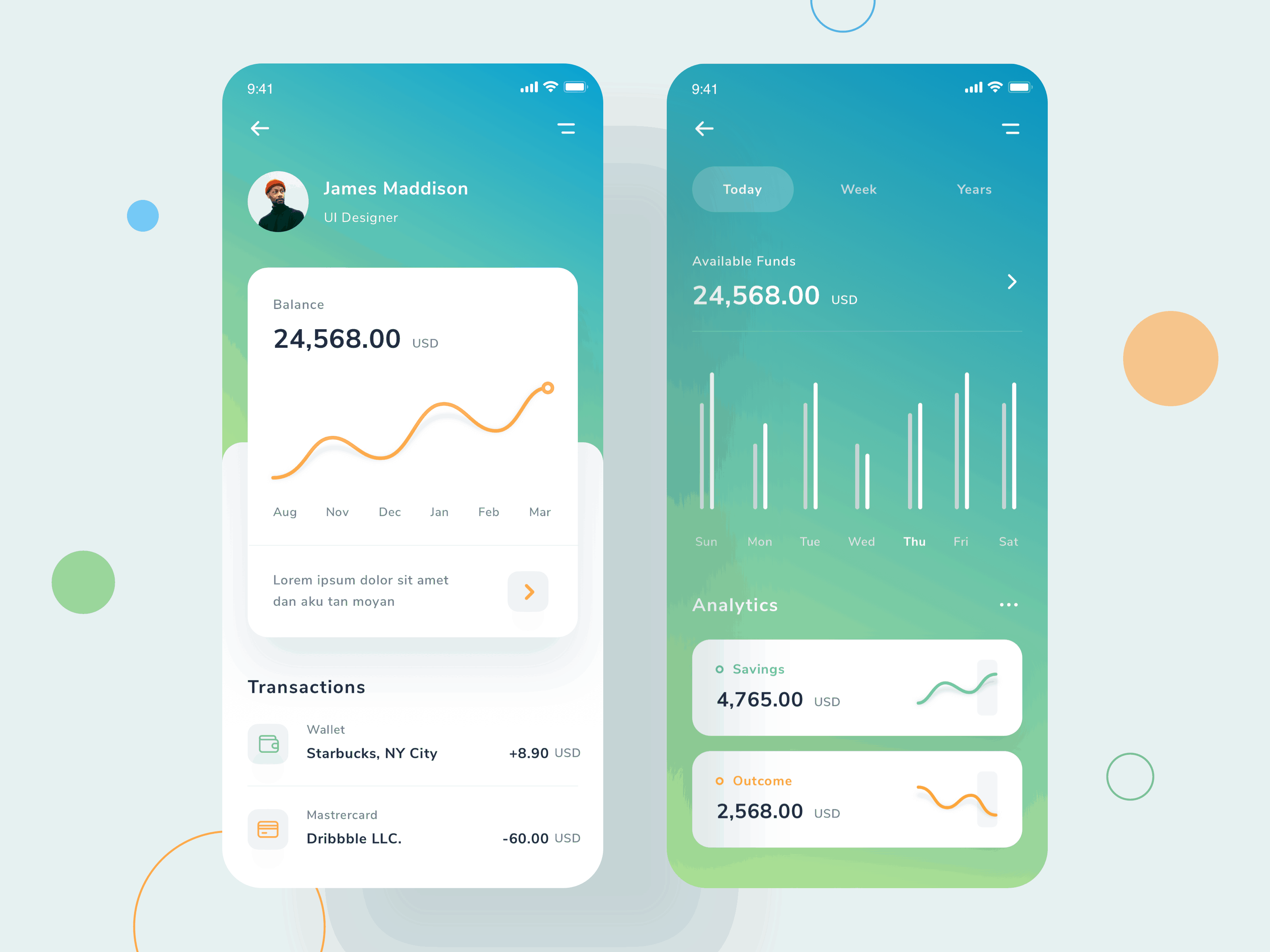

Airtel, its closest competitor, had 16.7 million data subscribers in Q1 2020. Another report also shows that 78% of Nigeria’s internet users are between the ages of 19 to 35. It may explain why many of these banks are going for a look and feel that is colorful and hip.

Digital banks as a niche service

How popular are digital banks with the older generation? What are the odds that your parents know any of the digital banks currently operating? How about the traders in Alaba, Computer village or even Aba?

While these people in the older generation use banks, their adoption of other technologies like bank apps remain low because of a mix of factors. Bank apps need you to have mobile data and are only as good as the internet service in your area.

Unlike mobile bank apps, USSD is offline, supported on all devices and is available everywhere you have telephone reception. It is also instant. In a low trust society like Nigeria, USSD bridges the trust gap.

Yet despite the popularity of USSD, physical bank branches are important to many people. In many market clusters across Nigeria, bank branches see a lot of foot traffic with customers coming in for transactions they can easily do with an app.

One thing is clear, beyond pushing USSD adoption, banks have done a poor job of improving adoption of their mobile apps.

If banks have been unable to get a lot of older people to use mobile banking apps, what are the odds that digital banks will be able to get them on their platforms?

It means that the segment that’s a realistic target for digital banks are young people who form 78% of Nigeria’s internet population. Tech savvy 20 somethings and 30 somethings who already have a ton of apps on their phones. They’re more likely to be swayed by the idea of an easier, more colorful approach to banking.

But it is worth asking if this segment is a big enough market size. While that’s up in the air, there’s nothing to say that digital banks have succeeded in making people dump their legacy banks.

Are people dumping their traditional bank accounts?

For a lot of young people, their first bank accounts are opened for them by parents or relatives. Most University students for example, choose the bank accounts their parents already use, or one with a branch close to their parents home or office.

Second and third bank accounts are often post-University choices that are tied to bank accounts you’re forced to open to receive the stipend for National Youth Service. But there are other patterns to how people open bank accounts.

People sometimes open new accounts when they relocate and need a bank that’s close to them. In the informal market, this kind of nearness is super important. The common thread is that the average person gets into the traditional banking system early and continues in the system for a long time.

Ironically, this does not suggest that legacy banks are great. Instead, it is that many older people are used to the idea of the bank as a physical touchpoint. For those in the informal market, large transactions with USSD seem risky because mistakes happen.

Accounts may get debited twice and networks could be down. The physical bank structure represents certainty. So, while many complaints about the traditional banks remain, it has not automatically meant adoption of its digital competitors.

So, while you might have an issue with a failed transfer or a wrong debit on your account, you know that there’s a bank branch you can walk into and resolve these issues.

Beyond this need for a physical touchpoint, many people are not dumping legacy banks because of one interesting reason: access to credit.

Digital banks are missing out on the loan front

Right now, many digital banks (with the exception of Kuda bank) only take deposits and do not offer their customers access to loans or other forms of credit. In a market that is ripe for credit facilities, this is a big miss for digital banks.

All legacy banks have their own lending product, especially since the CBN increased the ratio of deposits banks must loan to customers. To qualify for these loans, you have to show some inflows in your accounts for a defined period of time. You can also get many of these loans by dialing a shortcode.

This means there’s an extra incentive to maintain a legacy bank as a “main account.” Also, since access to credit remains a big need in Nigeria, this is one way banks have retained superiority.

In fact, banks often offer better rates than many of the specialised payday lenders. If digital banks won’t offer credit, are there other ways to think about increasing adoption?

Targeting salary earners as a means of adoption

In real time, one of the factors that determine how much you use a bank account is the inflows into that account. For many people, that means a salary account.

Actively using a digital bank for me would mean that on a monthly basis, I would have to make transfers from my salary account to the digital account. While that is seamless these days with USSD, it’s often an extra step I’m too lazy to take.

It often feels like having to transfer money from one bank to another defeats whatever convenience I’m supposed to get. One way that would take away this process is for digital banks to become my primary salary account.

This way, it would begin to find ease and convenient use, and things like free or cheap transfers could begin to matter. While many multinationals ask employees to use current accounts as salary accounts, there are lots of small or medium businesses in Lagos that are happy to pay staff salaries to savings accounts.

While this is a good place to start, it feels like the real answer to the question on how digital banks will drive adoption is a hyper-focus on solving only one problem.

Is the solution to think small?

“The difference is they’re not going for mass market [anymore]… they’re getting a core proposition.

“The ones who are going to survive are the ones with a core niche.”

-Jeroen De Bel

In Europe, some of the biggest digital banks are reporting big losses. A large part of these losses are because of expansion plans.

The popular thinking is to try to reach as many people as possible. As their losses show, this strategy is expensive.

A counter strategy for digital banks is to flip the switch and target a smaller crowd.

What will digital banking look like if it’s a premium service that’s not looking to cater to everyone? First, it will move from offering generic banking services to a hyperfocus on one or two products.

This kind of focus may mean creating a digital bank that totally solves the problem of transaction disputes for customers.

Zenith Bank’s recent earnings report showed that over 70,000 customer disputes remain unsolved for the year.

It would be useful to create a service that is dedicated to solving customer issues in one day. Imagine bringing Amazon’s customer obsession to banking.

If we stretch the Amazon example further, digital banks could go ahead to make a bundle of premium offers that traditional banks do not currently have. A bundle of excellent customer service, financial planning and credit reporting.

This type of focus on important customer problems can be good enough to charge a subscription fee for.

Instead of a digital bank that saves me an inconsequential N10 less on transfers, how about a digital bank that caters to Muslims and can guarantee that their monies will not be invested in certain industries?

Most importantly, moving away from targeting the mass market will ensure that digital banks don’t become like the traditional banks they want to replace. Traditional banks try to be too many things to too many people and often fail at it.

For digital banks, solving real problems for a few could be the route to scale.