My Life In Tech is putting human faces to some of the innovative startups, investments and policy formations driving the technology sector across Africa.

James Baldwin says, “History is not the past. It is the present. We carry our history with us. We are our history. If we pretend otherwise, we are literally criminals.” While he resounded this caution during the Civil Rights Movement of the 50s and 60s, it could never be more apt for now, in 2020, in Nigeria as young people fight to regain the soul of this country.

This week, in replacement of our usual individual profiles of people working in technology across Africa, we are turning the spotlight to platforms documenting and archiving human interest stories about this period to ensure that we carry this history with us. We speak to some of their creators and administrators about the platforms, how they source and verify information among others.

Here’s a brief summary of the events of the past week: anger and frustration over the activities of the Nigerian Police Force, particularly the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) unit came to a head last week after a video of a young man shot in Delta State, supposedly by officers of the unit, went viral. From a Twitter hashtag, protests burst out onto the streets of Lagos and has since spread across to more than 50 locations in the country with disporans in Berlin, London, Switzerland, the US among others marching in solidarity. Despite originating on Twitter and spilling into the streets, Twitter has remained a very critical tool in fundraising, organising, disseminating vital information, location/protest environment updates and galvanising action to free arrested and detained protesters or to provide medical aid to injured protesters. Requesting for and sending refreshments and supplies like water, masks and anti-teargas sprays have also not been left out. Twitter has remained the administrative and commandeering headquarters in the last seven days, one big Slack channel.

Up until Friday, October 9, protests went on without any hitches until police began meeting the groups with violence. There were reports from Abuja, Delta, and Ogbomoso where the first casualty of the protest was recorded on Saturday, October 10: 20-year-old Jimoh Isiaq, a student at the Ladoke Akintola University. Incensed by the sheer violence that the officers have resorted to, protests intensified on Monday, October 13, so much that Lagos was enveloped in standstill traffic with protesters blocking major roads and mobility points like the Lekki Toll Gate on the Lagos island. In Surulere, when officers opened fire at protesters, a driver who had stepped out of his vehicle to ease himself was caught in that mayhem.

Okechukwu Ilo was shot dead with his hands in his pocket, as undisturbing of the peace as one could possibly be.

On protest grounds across the country however, have been newly shored up stories of missing family members or those murdered by officers of this police unit and whose names and stories have not come to public light until now. We have seen as protests have unfolded in the last seven days as protesters have been arrested and framed for murder, a modus operandi this police unit has been known to resort to time and time again. Legal representatives are resorting to recorded videos and photographs to counter these claims. We’ve been able to tell, following the announcement of the Inspector General of Police and the President at different times that the unit has been disbanded, that it was disbanded twice in 2019 , in 2018 and the year prior from past records of similar announcements.

In a few years from now, how much of this period will we be able to recall as accurately and holistically as possible? How much of this history will we carry with us?

A few digital platforms have already sprung up in the past week and before the onset of these protests, who are documenting and archiving the present for the future.

The Police Brutality in Nigeria (POBIN) Project came two months earlier. Writer Kemi Falodun had, in 2018, written a story about The Apo Six, a 2005 extrajudicial killing by the Nigerian Police in Apo, a settlement town in the country’s capital, Abuja. It was the 13th anniversary of their deaths. Two of the officers involved were to be executed and one would later be promoted to the Assistant Inspector General of Police in 2018.

Every new story that makes it out either on social or news media is often followed by outrage but because tweets and posts are often swept away by the constant cycle of current issues, Falodun thought there could be more done in documenting and humanising the victims of police brutality in the country. A curation of this nature is also often how the magnitude and scale of this problem is better understood and conveyed.

Socrates Mbamalu, a writer and volunteer member of the POBIN Project tells TechCabal the stories often begin with news that makes it to social media. But the team almost always attempts to find a family member or someone who has a personal link to the victim.

“Other times, we can’t get to the people involved so we either listen to interviews across other media platforms and see what other media houses have mentioned, compare and contrast, then write the story and try to humanise as much as possible,” Mbamalu says.

“What we also intend to start doing right now is to travel to visit the families of the victims and talk to them.”

Right now, most communication with personal contacts are restricted to phone calls.

Following a grant received from philanthropic organisation, Gatefield Impact, and interest from more volunteers, the team is already working on documenting the current #EndSARS protests and its casualties. So far, at least ten people have been killed since October 9 according to Amnesty International.

“If you take a look at the Civil Rights movement in the 60s which was well documented, you will see that they were able to draw a pattern from that point in time to the point where they are currently and it is because there was documentation of some sort,” says Mbamalu.

“And that has to be done in this case. In 20 years, if this comes up again, people may think this is a new thing and it wasn’t happening years ago. There is the need to show that there has always been this issue happening in our society and that the people that were killed were not just unnamed people but people who had lives, dreams and that had futures.”

While technology and digital records of these events certainly aid their collection for POBIN, Mbamalu is quick to point out that it also presents a challenge in finding the stories that do not make it to Twitter and Instagram or any news publications. One way POBIN is working around this is connecting with community leaders on ground to connect with family members of victims but also the possibility that they can become the ears and eyes of the organisation for the stories that will not make it online.

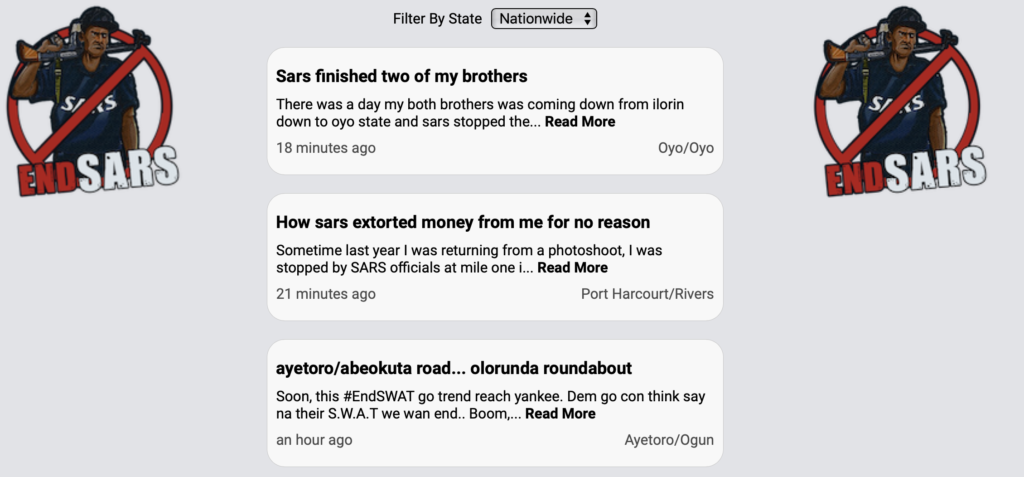

Endsars.com is an endless scroll of curated stories from Nigerians about being harassed by SARS officers. The stories come from across the country, from Lagos to Abuja, Delta to Anambra and paint a dreadful picture of why these protests have been sustained this long. Majority of Nigeria’s young have had terrible personal encounters with this police unit or know at least one person who has. In addition to written stories are also images from protesters, videos, SARS sightings (this is supposed to alert commuters to the presence and operations of the unit in a particular area in real time). According to information on the platform, the submitted stories are being verified before they are published but it is unclear what this process looks like. For security reasons, the founders declined speaking with TechCabal and requests for comments have yet to be responded to.

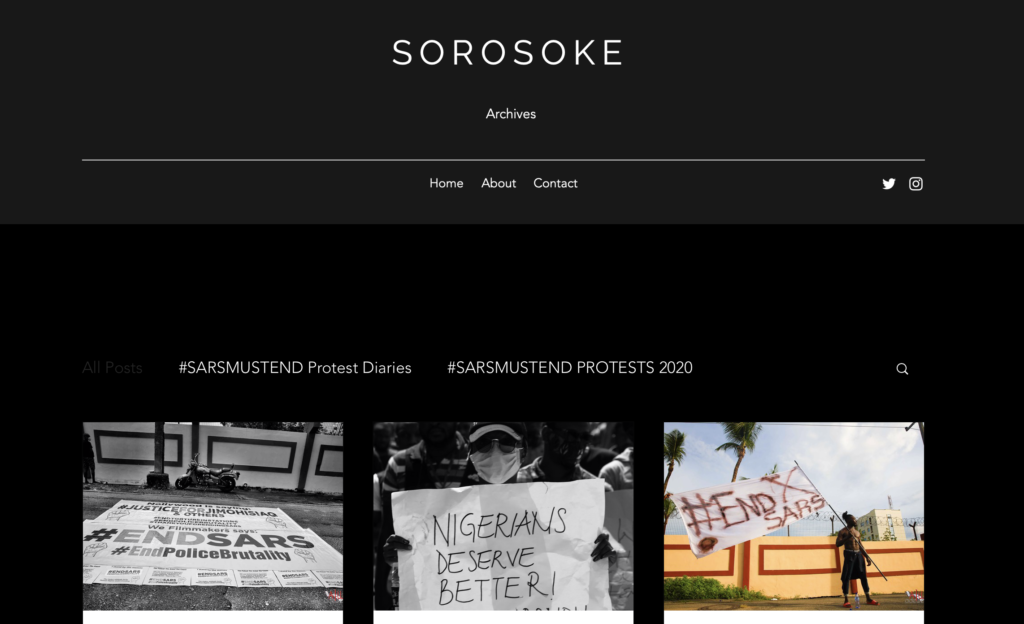

Sorosoke (speak up! in Yoruba) was launched by Fatimah Binta Gimsay, a screenwriter who tells me not being physically present at the protests led her to thinking about more substantive ways to contribute. She created Sorosoke as social media archival pages on Twitter and Instagram to house visual stories from photographers across the country who have produced some iconic and powerful images since the beginning of the protests.

“I realised Instagram and Twitter can get suspended at any time but a website is like a journal,” she said.

The logos, the social media accounts and a website were set up under 24hours. The website is powered by Wix. In addition to sourcing for photos online, the platform is open to photographers to submit their images with appropriate descriptions and credits.

Gimsay says she hasn’t had a SARS experience but a number of her friends have. What she has encountered, however, are harassment incidents from armed security or law enforcement officers. The most recent occured three weeks prior and involved a Lagos State Traffic Management Authority (LASTMA) who “made me transfer ₦20,000 ($53) to him on the spot”.

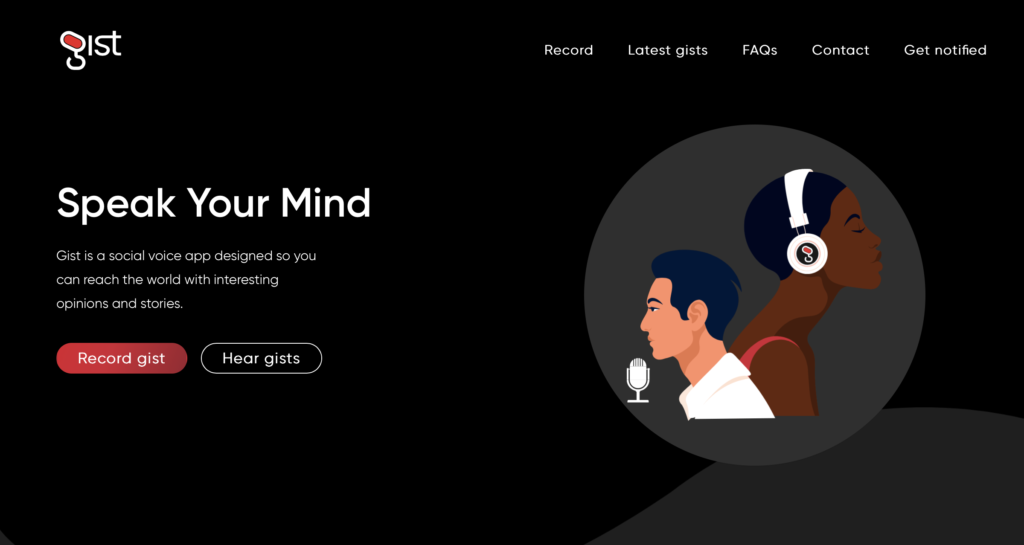

Other platforms like Gist Audio are curating audio stories of SARS experiences both past and at the ongoing protests. The platform which launched in August allows you record a 3-5 minutes long voice note and upload in mp3 format on the platform.

Sustaining these records digitally, however, will require a lot of effort including dedication to keep the records alive, accurate and updated, funds for technology infrastructure as well as personnel who will cater to things like verification of information among other things.