In 2019 alone, recoverable material like gold, silver, copper, platinum and other such materials worth US$57 billion were lost to improperly recycled electronic waste.

Not many of us consider how we dispose of or will dispose of used electronic and mobile devices after they’ve served their purpose. While researching this topic two years ago, many individuals I spoke with said they disposed of their devices either by selling or passing them down to second-hand users or to the informal scrap metal industry where a large percentage of used electronic equipment go to be recycled.

These players take the items apart, extract what is useful to them using largely crude techniques and dispose of remains in landfills and incineration sites where the degradation of these equipment go on to contaminate everything they come in contact with, from the soil to surrounding water bodies and the aquatic lives in it.

Global conversations around climate change have stirred action about single-use plastic and increased awareness about the need to adopt more sustainable materials across various sectors.

But it would seem, with the increasing manufacture of short-term cyclic technology products, there isn’t enough noise being made about how these shorter life-spanned gadgets are being disposed of. They have as much if not more harmful effects on the environment and in human/animal life as do plastic.

The past year saw a record increase in the amount of electronic waste generated according to data gathered in The Global E-waste Monitor 2020: Quantities, flows and the circular economy potential report.

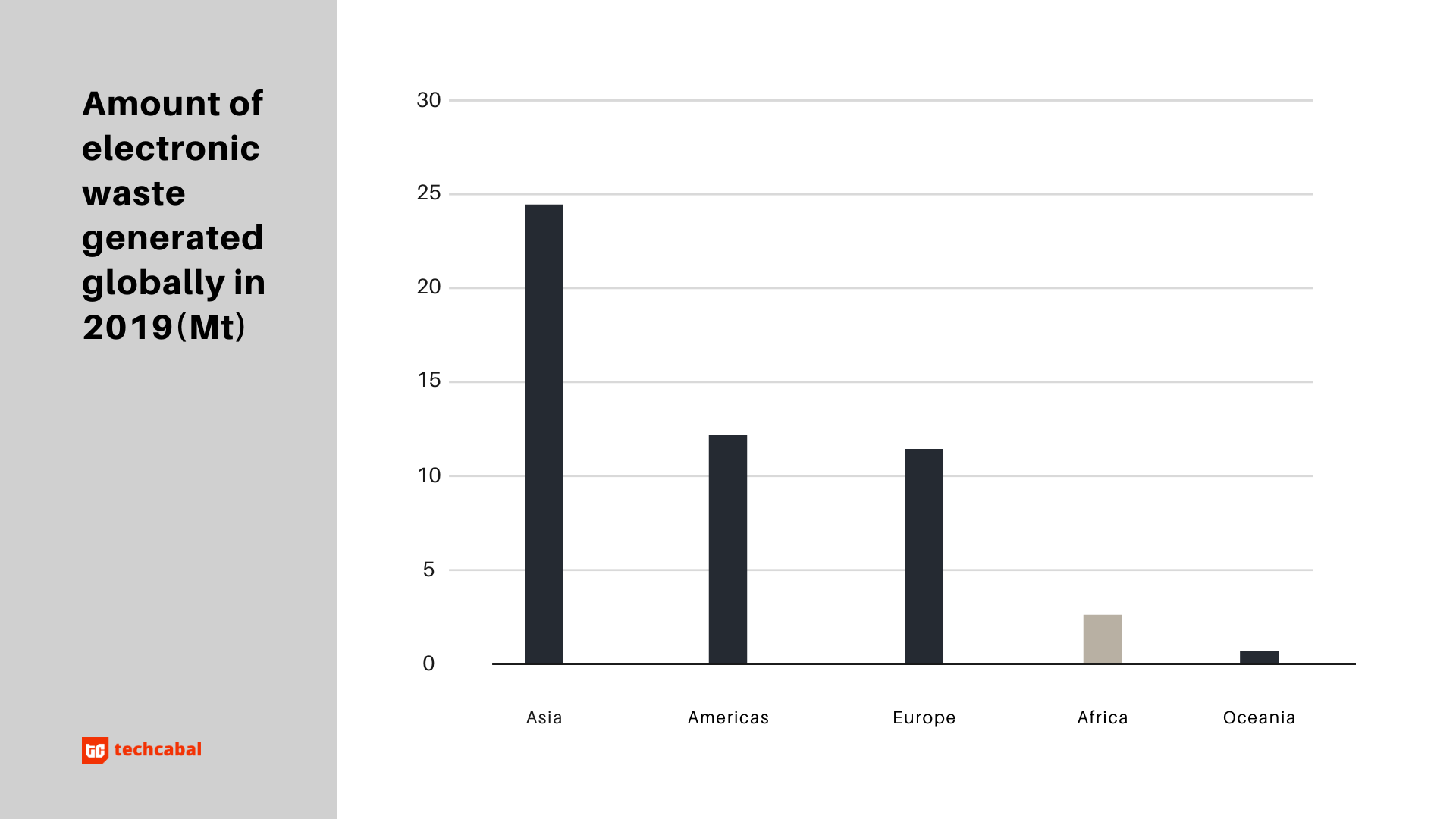

Amount of electronic waste generated globally in 2019

In 2019, 53.6 million metric tons (Mt) of electronic waste were generated globally and only 17.4% of this was officially documented as properly collected and recycled. According to the report, total e-waste generation increased in 2019 increased by 9.2 Mt from 2014 and is an indication that recycling is still not at pace with the speed of e-waste generation across the world.

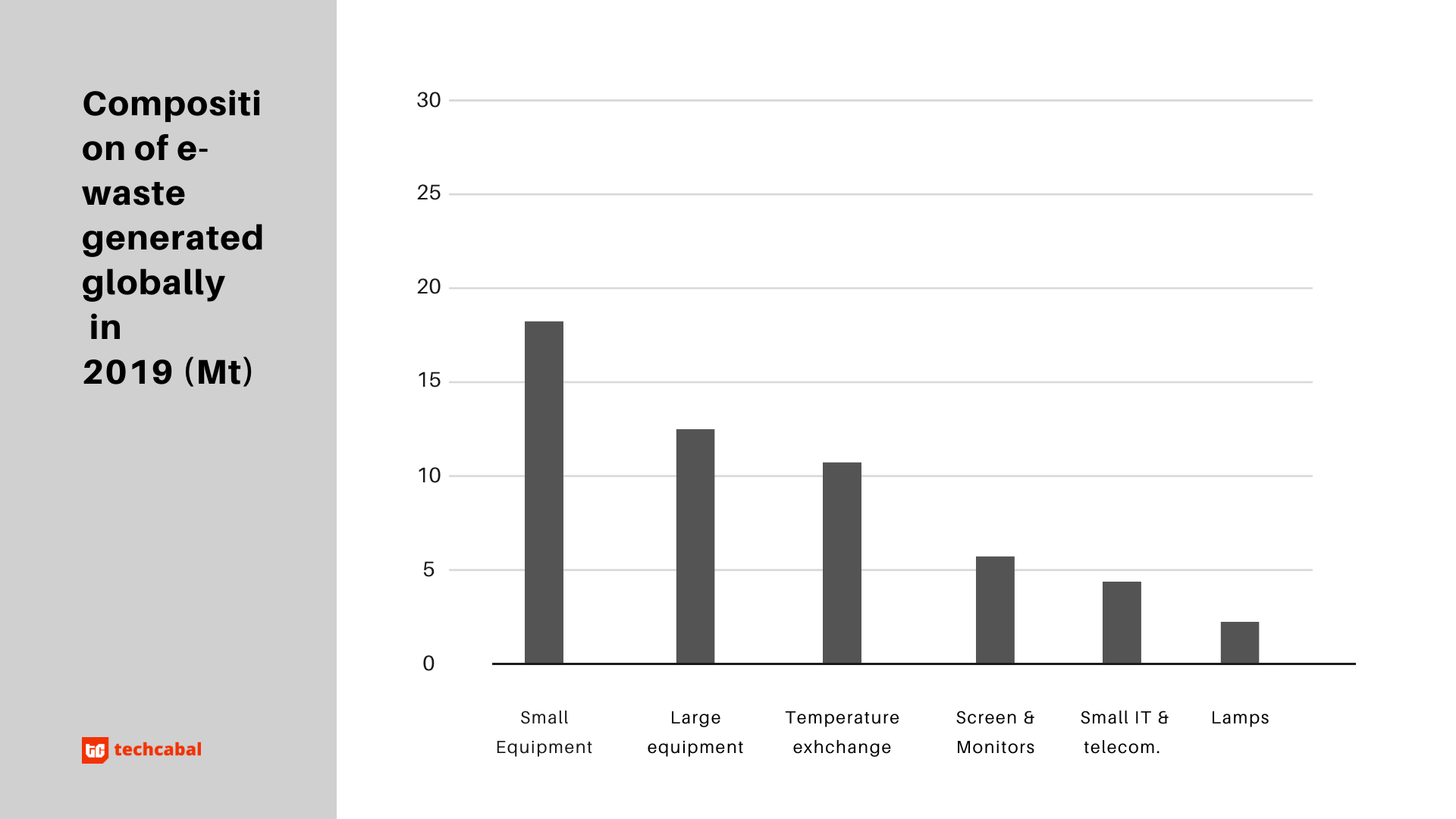

In terms of composition, the most amount of e-waste generated in 2019 falls into the category of Small equipment. This includes electronic and electrical equipment (EEE) like fans, cameras, radios etcetera. At the other end of the spectrum are items categorised as Lamps which include every light giving device from bulbs to torches.

Painting a larger picture, EEEs categorised as Temperature exchange equipment (air conditioners, refrigerators), Large equipment (gas cookers, dishwashers), as well as EEEs in the Lamps and Small equipment category are increasingly comprised in the total weight of e-waste generated globally. They point to an increased need for improved quality of living and less reliance on manual labour in many households.

Composition of e-waste generated globally in 2019

While compared to other regions the African continent produces less amount of e-waste, a significant amount of its e-waste volume results from transboundary movement of e-waste across regions typically across the global North-South route. Studies from last year as discussed in the report indicate that there is an increasing dynamism about the transboundary movement of e-waste beyond the global North-South route.

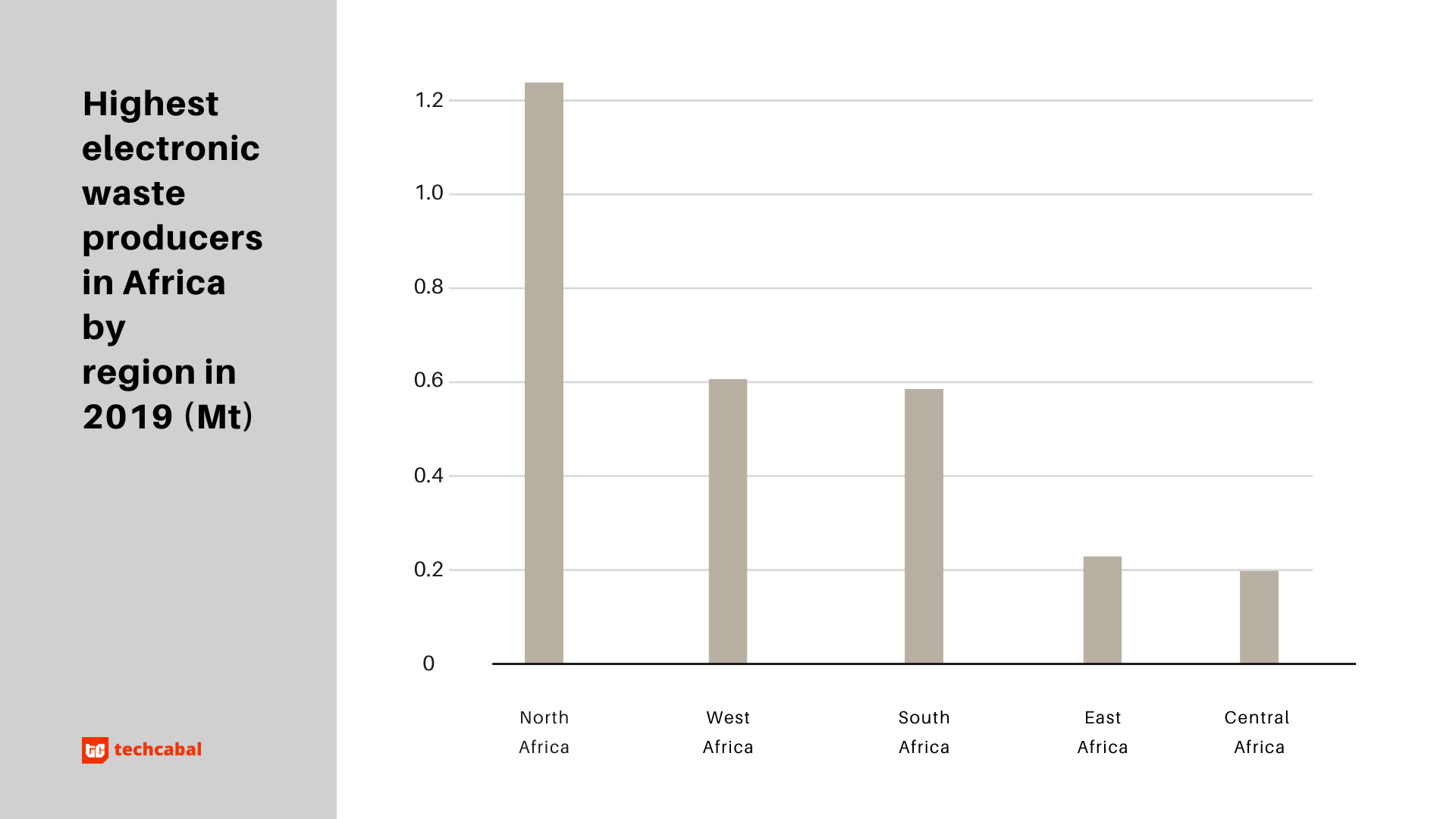

In the continent, North Africa produced the most e-waste in 2019 at 1.3 Mt while countries in the Central Africa region produced the least at 0.2 Mt.

North Africa produces the most e-waste across the continent

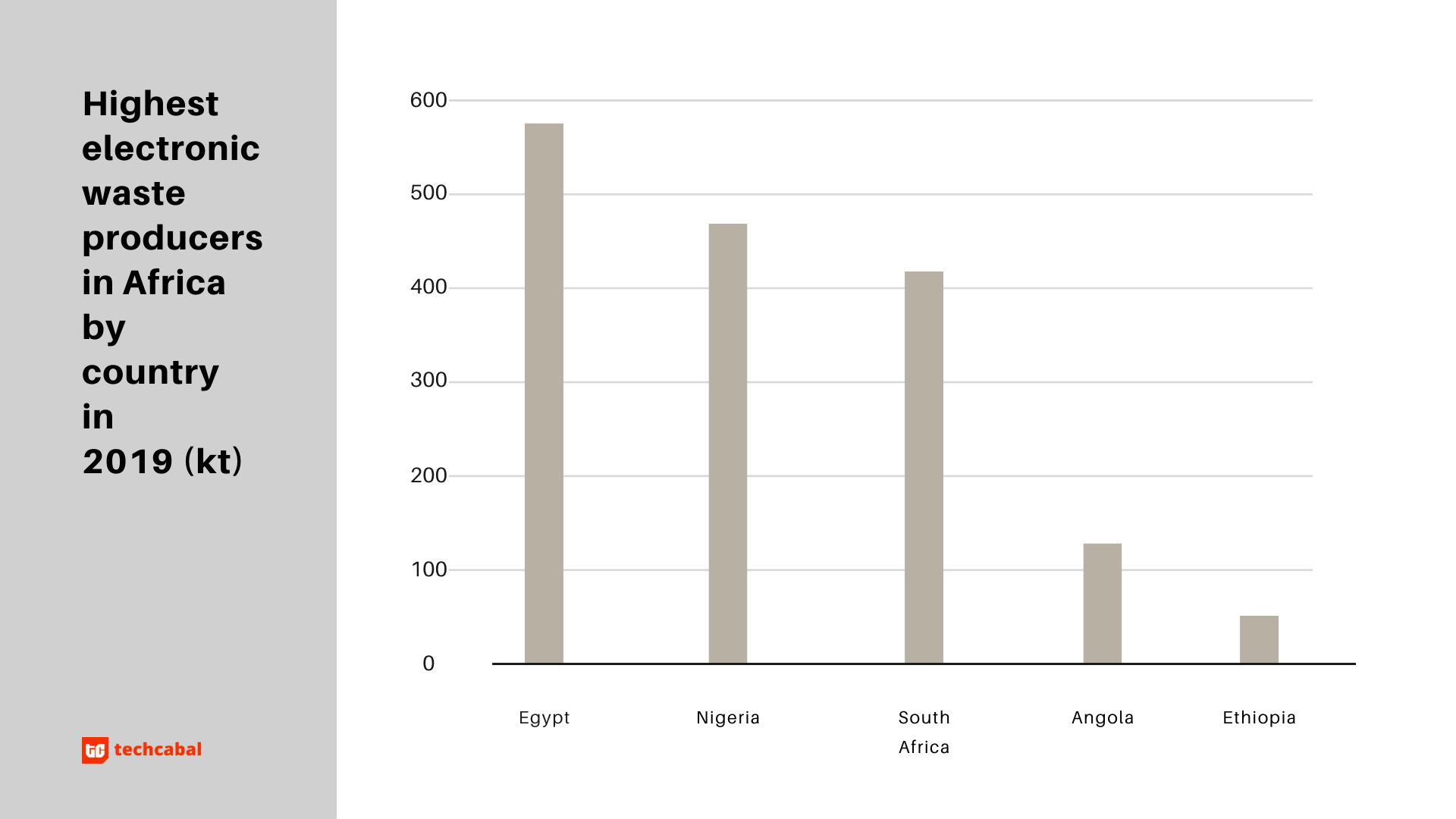

Nigeria, Egypt, South Africa, Angola and Ethiopia are leading across the continent for the most producers of e-waste.

Higher consumption of electrical and electronic equipment (EEE) as fuelled by increasing urbanization, higher disposable income and industrialization have been said to account for a marked increase in the production of e-waste in the continent. Ownership varies across income levels with those within the low income level still able to account for mobile phones, electric lamps/bulbs, and perhaps a refrigerator.

There’s also the shorter lifespan and cyclic nature of smaller equipment like mobile devices with very little known formal routes of recycling or takeback programs by manufacturers and wholesalers.

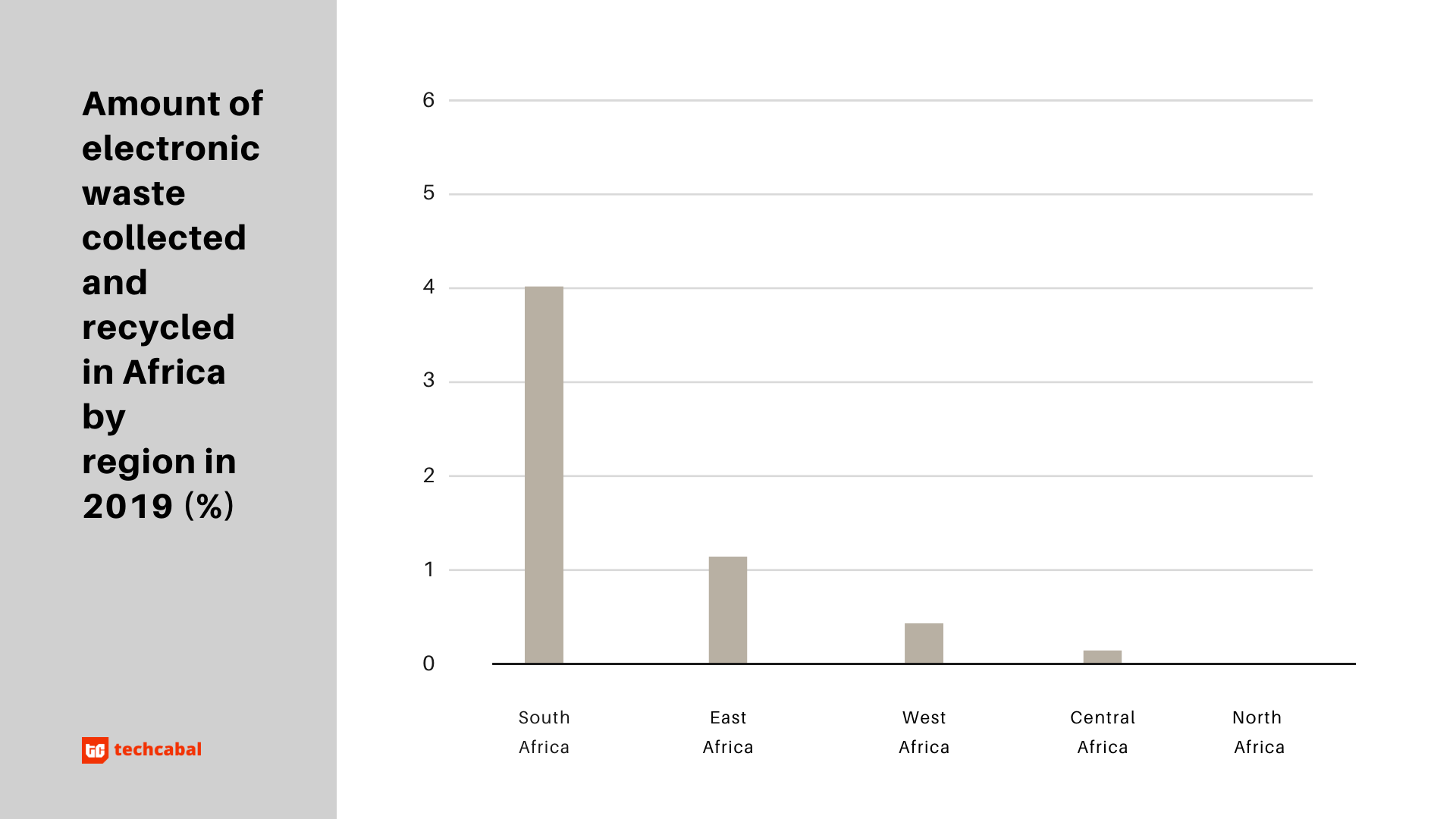

Only 0.9% of e-waste generated on the continent in 2019 can be said to have been accounted for and recycled appropriately. Most of this collection and recycling was recorded in southern Africa with no activity recorded for the north Africa region in the period.

In most parts of the continent, informal recyclers supersede formal recyclers who are few and often do not come to mind at first when an individual considers how to dispose of an electronic or electrical equipment.

In countries like Nigeria, regulatory bodies like the National Environmental Standards and Regulations Enforcement Agency (NESREA) have ratified laws to enforce responsible collection and disposal of EEEs. The creation of the E-waste Producers Responsibility Organization of Nigeria (EPRON) in 2018 has brought together stakeholders in the space including large corporations like Microsoft and Helwett-Packard to commit to introducing measures to increase the ethical collection and disposal of e-waste.

Similar regulatory and policy moves have been made elsewhere including Rwanda, South Africa, Cameroon and Ghana where the largest scrap metal and e-waste dumpsite in Africa now resides.

Only a very small fraction of e-waste produced in Africa is responsibly collected and recycled

According to Dr. Ifeanyi Ochonoghor, CEO of E-Terra Technologies, in Nigeria, only two formal e-waste recyclers are in operation and the industry remains dominated by informal players not only in Nigeria but the rest of the continent.

“Federal and state governments through their waste management and

environmental protection agencies still need to do more to create awareness on the existing e-waste crisis in Nigeria, set-up e-waste drop-

off/collection centers nationwide to evacuate e-waste, drastically curtail the activities of crude informal e-waste recycling in our communities and

enforce the existing e-waste and data protection laws in the country without fear or favour,” Ochonoghor stressed.

The general lack of public awareness about the dangers of these kinds of waste make it even more difficult to tackle. Many know plastic is bad, but not often do they think about how an old phone or toaster burning in a landfill in their state or county might be problematic.

Also, despite existing laws that regulate the transboundary movement of e-waste, there’s still a lot of work that needs to go into effecting and upholding them to stub the inflow of e-waste especially into regions like Africa where a substantial percentage of these imports are outdated or dysfunctional and not at all beneficial to any segment of the population.

In light of an eventful year, Ochonoghor says there may be a slight contraction in electronic waste generation globally in 2020. At E-Terra, the coronavirus pandemic year has brought both great news and some tragedy.

While the company added new service lines for Cable and Florescent bulb treatment and secured a lucrative e-waste recycling contract with a major original equipment manufacturer (OEM) this year, a pipeline explosion in March 2020 damaged its Material Recovery and Recycling Facility (MRRF) in the Abule-Ado area of Lagos where the incident occurred.

“We spent a fortune to renovate the facility as it constitutes the most essential component in our recycling value chain,” he told TechCabal.