“When it doesn’t come out right, they blame the editors.”

Chuks Oteke had had enough of the complaints about his work. In 2012, he set up his video production studio where he provided visual effects and video editing services, but every now and then he received complaints from clients who were dissatisfied with his work. To them, Oteke was the problem but to him, the problem was the raw video cuts he got from his clients.

The shots taken on set didn’t really tell the story and the clients believed that any shortcoming could be fixed in post-production.

When he couldn’t take it anymore he decided to look into why the shots were poor. He took on different camera operator jobs on different video shoot sets. At the end of his research, he came to the conclusion that the camera operators didn’t have the right tools to get the right shots.

“To tell a good story, it’s not just about the camera. You need to position the lighting right, you also need to frame the shots appropriately. If a character is feeling depressed, the camera angle should help depict depression. High angles help with this by making the actor seem small or overwhelmed. On the contrary, a low angle helps in depicting joy or happiness,” he said.

In some cases, a crane is needed to achieve these shots but how many people can afford it?

This informed his decision to go into creating tools for shooting videos. He started with making prototypes of DIY tools. It didn’t officially become a business until some people offered to pay him for the tools.

“So I started making noise on Instagram and Facebook about how I make customised DIY tools and the response was good. It got to a point where there was so much demand I just couldn’t meet up with it.”

This birthed Film Anatomie, one of the few African companies designing and manufacturing filming equipment. It caters for a wide range of clients such as independent content creators, filmmakers, television studios and even equipment rental companies.

Getting into General Electric (GE) Garage

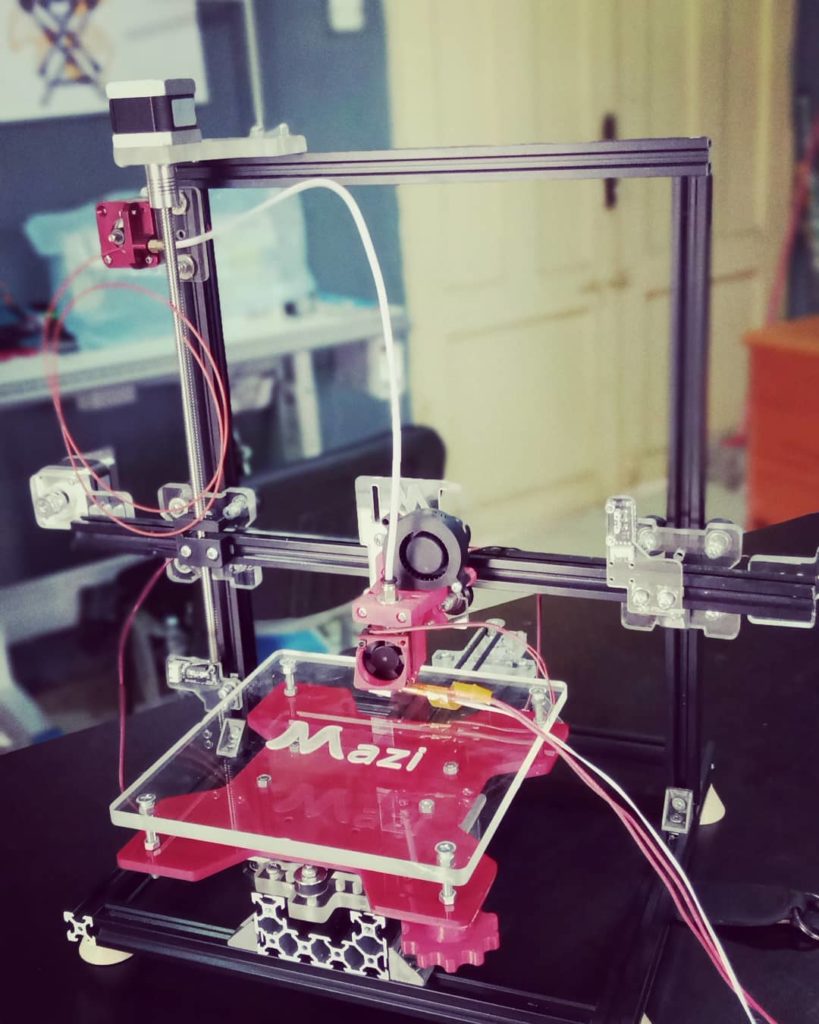

High demand could have fooled someone else to think they were in business but not Oteke. He quickly realised that he wasn’t knowledgeable enough to turn his interest into a business so he enrolled in the General Electric (GE) Garage Program in 2014. During the training program, which spanned across a few years, his mind was opened to advanced manufacturing techniques, 3D printing, laser cutting, etc.

He remarked that simply learning about product design influenced the design of his products.

During the program, Oteke met other participants who were into robotics, aviation, STEM education and biomedicine.

At the end, he had access to over a thousand local and foreign mentors in the tech space.

“I now had this network of people I can contact at any time and say, ‘I have this problem, how can I solve it?’ Definitely, there’ll be somebody who knows somebody else who can help.”

Difficulty in getting funding

Armed with this knowledge and network, he set out to run a better business. He knew where and how to get raw materials. It wasn’t possible to make everything locally but with 80% local raw materials the cost of production was low.

The next piece of the puzzle was finance. He needed a business partner as well as capital.

“I am a techie. I’m not a business person. So I was looking for investors who’d provide capital and also business advice. It took a while for me; other participants had already gotten investments.”

Graduates of the GE Garage Program were introduced to a pool of investors in their fields. While many of the other participants had business ideas that were seen as important, Oteke’s idea was seen as a nice-to-have. Investors showed little to no interest in him until the movie Lionheart was released.

How Lionheart changed everything

“I don’t even know Genevieve, I’ve never met her, but she doesn’t know what she has done for me.”

Genevieve Nnaji’s Lionheart made headlines in 2018 for its milestone as a pioneering Nigerian Netflix original. Finally, investors started paying attention to the creative industry. Oteke started getting some attention.

In an industry that barely has ready data, Oteke had to crowdsource and develop a realistic projection for his business. He found out that the Nigerian movie industry produces about 50 movies per week and generates an impressive $590million in revenue annually.

His pitch to investors was simple: the filming industry market is smaller than it will be in a few years time, it’s easier to gain a large market share now.

“Nigeria’s creative industry doesn’t have a repository but with Netflix you could see the views and how much was being paid. Lionheart was reportedly bought for $3.8m.”

Unfortunately, while it was easier to get overall industry statistics, he still had issues getting numbers because his target audience are moviemakers, not actors. He reached out to different production teams to get a sense of how much they spent on equipment and what the demand was like.

“I reached out to friends in film production and film schools. I established a relationship with Dell York, Jeta Amata and Olu Jacobs’ film school. I’m trying to establish one with Ebony life. We hope to grow to the point where you can come to us when you need the numbers for Africa’s creative industry.”

Getting Investment

After one of Oteke’s pitches at GE garage, an investor from Platform capital* reached out to him. The conversation, unlike others, looked promising.

“I remember I told him ‘I’m not really much of a business person, and I know you can help. You also have access to other markets like Asia, America and the UK’. He was quite open and he wanted to build a film academy, a production company, and [had] a lot of other creative ideas.”

Oteke finally got investment just before the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic made it difficult to get a few necessary things but was also a blessing because at that time they pivoted to making face masks with their 3D printers. It was a business opportunity that kept the lights on for a while before they returned back to their main focus: creating film equipment.

Offering free products to get customers

As the effects of the pandemic waned and filming activities began, Oteke and his team were tasked with finding customers. Unlike other popular filming equipment, people were hesitant towards trusting their expensive cameras and filming gadgets with less popular locally made equipment. Building trust was the next hurdle they had to jump.

“We found a way to mitigate that problem by offering our products for free. We targeted selected customers who could help us publicize our brand. For instance, I took my slider to where some big filmmakers were filming. I let them use my own on one camera while they use their own slider on the main camera. At the end of the shoot, I’d ask them ‘what do you think I can do to make this tool better?’ They’d tell me and we’d make the adjustments.”

A number of them were often satisfied, when they asked for the price, the price difference made Film Anatomie’s products more appealing. His sliders cost about ₦100,000 (~$220) while the existing more popular sliders with the same features are more expensive, costing between $500 – $1,000.

What’s next?

Oteke might have started making equipment for the film industry but at the heart of what he does is manufacturing where there’s a need. The goal for him is to manufacture for other sectors like 3D printing for car parts and household materials.

“In Africa, we don’t make anything, we just consume. There has been some success in the fintech space and agricultural space, but in the hardware manufacturing space we still worship China.”

He believes the future is in designing and manufacturing in Africa.

Oteke’s big project for the year is an electric vehicle that would be used for site inspections in real estate and for video shoots. The car would be able to ride on regular roads and on rough terrains.

For Oteke and his team at Film Anatomie, the vision to create homegrown solutions is massive. They’re focused on building and collaborating with others thinking in the same line.

*Platform Capital is an investor in Big Cabal Media, TechCabal’s parent organization.