Between November and December 2020, Tunji Andrews co-piloted a project to help informal workers save for the future. Those efforts culminated in the January rollout of Awabah, a digital platform that provides micro pension access to self-employed Nigerians and informal workers.

“Many people in Nigeria and Africa do day-to-day financial transactions in markets but don’t have access to the benefits that the formal financial system offers,” Andrews told TechCabal.

“So when I wanted to get into the fintech space, it had to be something that would drive financial inclusion on a very strong basis.”

A flexible, ₦500 plan

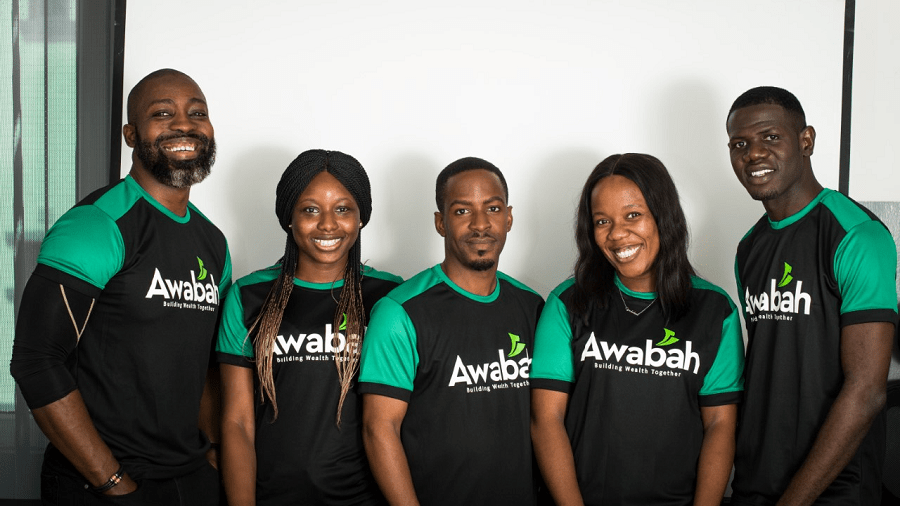

Co-founded with Tina Ajishebiyawo and Gboyega Olatunde, Awabah Nigeria automates micro-pensions and target-savings for self-employed Nigerians and workers in the informal economy. An understanding of the unique characteristics of its target market has been key to Awabah’s operations and ensuring last-mile delivery.

Lower-income members of the informal economy can be difficult to capture and most engage in local cooperatives and market associations. Awabah has leaned heavily on town hall meetings to reach these people in large numbers, introducing its product via group presentations and one-on-one sessions.

After onboarding them, the company uses either its web platform or a network of local banking agents to continue taking collections from, educating, and further engaging with contributors.

Income levels vary in the informal sector. Thus, Andrews explains that contributors with as little as ₦500 can start a micro-pensions account. Subsequent amounts contributed are based on an individual’s capacity.

Contributions are also flexible. Taking into account the irregular cash flow of informal workers, they can be made daily, weekly, monthly, or even quarterly, similar to local savings groups (popularly known as Ajo or Esusu).

Due to the constant need for cash flow in the informal sector, users have the option of withdrawing up to 40% of their savings at any point after the initial 3 months of contributions. Whenever someone deposits ₦1,000, for instance, ₦600 is locked in the retirement account while the rest goes into the customer’s mobile wallet as contingent savings.

“They always come and ask for their 40% after the first three months as a way of testing the product, and we make sure that they get it as quickly as possible,” Andrews said. “Once they get their money back and see alerts every time they put in their ₦500, they’re able to test the system.”

Awabah has achieved impressive results within months of operation, having onboarded more than 5,000 customers so far. It makes money primarily by earning a commission on every contribution made.

Extending pensions to the informal economy

In Nigeria, a good number of elderly parents are financially dependent on their children – partly because societal norms deem it necessary for children to care for aging parents; and also because there is an evident lack of working systems for retirement savings.

Even where pension schemes are available, they often only cover people who are formally employed. Nigeria has a large informal workforce and about 88% of the entire labour force without pensions is from the informal economy. The result? A large group of citizens becomes financially vulnerable as they get older.

Worse still is that relatively young Nigerians currently dominate the labour force and the lack of retirement savings means they are susceptible to living below the poverty line in their old age.

Nigeria’s National Pension Commission (PenCom) has a target of growing the country’s pension coverage to 30% of the entire labour force – formal and informal – by 2024. As of the first quarter of this year, the figure stood at 12%.

A provision in the Pension Reform Act of 2014 ushered in a new micro-pension plan, effectively opening the door for the informal economy to participate in the national Contributory Pension Scheme (CPS). Awabah’s operation is backed by this provision.

The micro pension scheme was formally introduced in 2019 but is yet to gain traction. Thus, Andrews has made it his and Awabah’s mission to make the services available to those in the informal sector and whose employers are not legally required to deduct and remit pension.

“When I heard about the new micro pension scheme two years ago, I was excited as I had been thinking about pensions. But there weren’t a lot of conversations and awareness about it. So for me, it was a no-brainer,” he said.

Expanding Awabah

Awabah is less than a year old and has had to deal with manpower and logistics challenges. Still, Andrews has big ambitions.

Going forward, the startup plans to leverage the penetration of mobile phones in Nigeria to reach even a wider audience, starting with the planned launch of a USSD option.

Through a shortcode, existing and potential customers will be able to learn about and sign up to Awabah, as well as get financial literacy lessons in local languages. For those who have smartphones, Awabah will engage them via WhatsApp.

The startup raised $200,000 from early-stage angel investors ODBA and Co Ventures and Correlation Capital in July, which helped it expand into Ibadan. Awabah also recently gained acceptance into the Techstars London accelerator programme, where it will get some funding.

Andrews reveals that a new fundraising round is in the works, which will help fund a larger expansion. Over the next few months, the startup has plans to enter into five more Nigerian cities. It is also mulling an expansion into Ghana.

“The bigger goal is to create a larger awareness of micro pensions in Africa,” Andrews said. “We want pensions to be popular as banking and insurance are.”

Currently, Awabah has partnerships with three Pension Fund Administrators, including Leadway Pensure, which holds the PenCom license under which it operates; a microfinance bank via which it provides mobile wallets; as well as two agent banking networks.

Andrews aims to expand the list of partner organisations and, in the long term, plans to push conversations with Nigeria’s pensions regulator on the possibility of issuing micro pension licenses for small players like Awabah.

“In Nigeria, we have a one-size-fits-all pension license, unlike Ghana where there’s a three-tier system,” Andrews said. “The lack of micro pension licenses can be a drawback as we believe we are best positioned to drive the product. But it’s still very early days.”

If you enjoyed reading this article, please share it in your WhatsApp groups and Telegram channels.