When millions were stuck at home during the 2020 COVID lockdown they were forced to increasingly rely on tech for communication, information, education, entertainment and commerce, which translated to skyrocketing revenue and user base for tech companies, who in turn hired more employees and expanded to new territories to keep up with this unprecedented growth in demand.

That year, Facebook (now Meta), after seven years of operating its Johannesburg office, announced that its new Lagos office would house a team of engineers. It was the first time Meta was expressing optimism that a local African office can build products for the continent and the rest of the world. This coincided with the beginning of a romanticisation of Africa by the tech community.

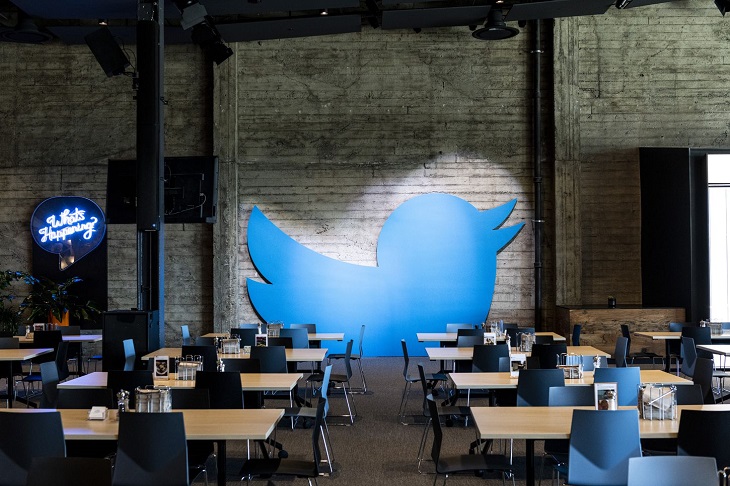

Earlier in 2019, Twitter’s then-CEO, Jack Dorsey, had rounded off an African tour by pledging to stay on the continent for a few months in 2020. In 2021, Twitter announced that it was setting up its first office in Africa.

Africa’s tech ecosystem was burgeoning and was minting both startups and tech at an impressive rate. Everything seemed to be going well until wasn’t.

Soon after, tech went burst. Fallouts of the Russia-Ukraine war, reduction in ad revenue, increased competition for advertisers’ dollars, and dwindling stock market prices have brought tech to its knees. Tech companies which benefited from outsized revenue growth as a result of the pandemic are cutting down their investments for capital efficiency. After Meta sacked 11,000 employees, CEO and founder, Mark Zuckerberg admitted that he and many other people made a prediction “this would be a permanent acceleration that would continue even after the pandemic ended.” Jack Dorsey, who has since left the helm of affairs at Twitter, admitted to having hired too fast when Twitter laid off 3,700 employees earlier this month. But where does this leave the African offices of these giant tech companies?

Future of Big Tech offices in Africa

Earlier this month, the newly assembled 20-person Twitter Africa team celebrated the launch of their office in Ghana, but in less than a week Twitter’s new owner, Elon Musk, sacked most of them during his mass layoff of 3,700 employees. This raised many questions about the importance of Africa as a market for Big Tech. Many asked why Musk couldn’t have retained the new team since they were small in size and served over one billion people.

The team’s work provided cultural contexts across Africa’s 54 countries and moderated content in some of the most fragile places in the world, including Ethiopia.

Oftentimes, when a big tech company opens an office on the continent, it is usually to represent diversity, establish relationships with the home government, or create non-technical teams. Sadly, non-technical workers in tech are disposable, as can be seen in the recent Twitter layoffs: Musk fired the entire content moderation, curation, safety and truth, and communications teams globally. Unsurprisingly, the layoffs-affected Africa office had no engineering team but curation, content moderation, sales, policy and communications teams. It’s evident then that in a tech world of fewer handouts and diversity offices, the future of Big Tech offices on the continent remains uncertain.

One would think that the presence of an engineering team that worked closely with Twitter’s global engineering team, and India’s status as one of the world’s largest markets, would save Twitter India’s office workers from the sack hammer, but it didn’t. Elon sacked 90% of Twitter India’s 200 staff members. The Indian team, however, got a 2-month severance package, the US team got a 3-month package, while the team in Africa are getting nothing. India’s preferential treatment might not be unrelated to the several run-ins Twitter has had with the Indian government.

Creating global value from Africa

In truth, commercially, the African market brings in little money for these global Big Tech, which explains why the continent ranks low on their priority list for expansion and product availability. For context, in the fourth quarter of 2020, Facebook’s earnings from the US and Canada alone were 20x more than what it got from Africa. Although Africa’s lack of economic attractiveness is complemented by a large population that is set to grow to the biggest in the world, not every tech company can afford to make long-term investments, especially during this tech winter. Most are here for a good time.

If Africa wants to be taken seriously by these US-based tech companies, first of all, its value must go up. Undoubtedly, Africa has solid engineering capabilities. Microsoft’s metaverse flagship product Microsoft Mesh is, after all, being built out of its Lagos office. Meta’s newly launched Lagos office houses a team of about two dozen engineers building Africa-focused edtech Sabee—although TechCabal has been unable to confirm how Meta’s recent layoff affected them.

African countries’ labour laws must also appropriately protect their citizens as mass layoffs become a norm in the tech world.

Creating a valuable market and ecosystem is central to priming up the continent’s importance in the eyes of these companies. The onus falls on African governments to create economic conditions that improve the spending power of these customers so that they can get a corresponding quality of service and overall importance.