₦200 billion. That’s how much Nigerian banks owe telecom companies for using Unstructured Supplementary Services Data (USSD) banking. That debt has been a source of friction between banks and telcos for six years and has needed the intervention of the Central Bank and the Communications Commission.

After a meeting in late 2023 produced a payment plan, three people with direct knowledge of the matter said the banks have now begun paying the debt. The Central Bank governor Olayemi Cardoso played a role in pushing the banks to pay, they said.

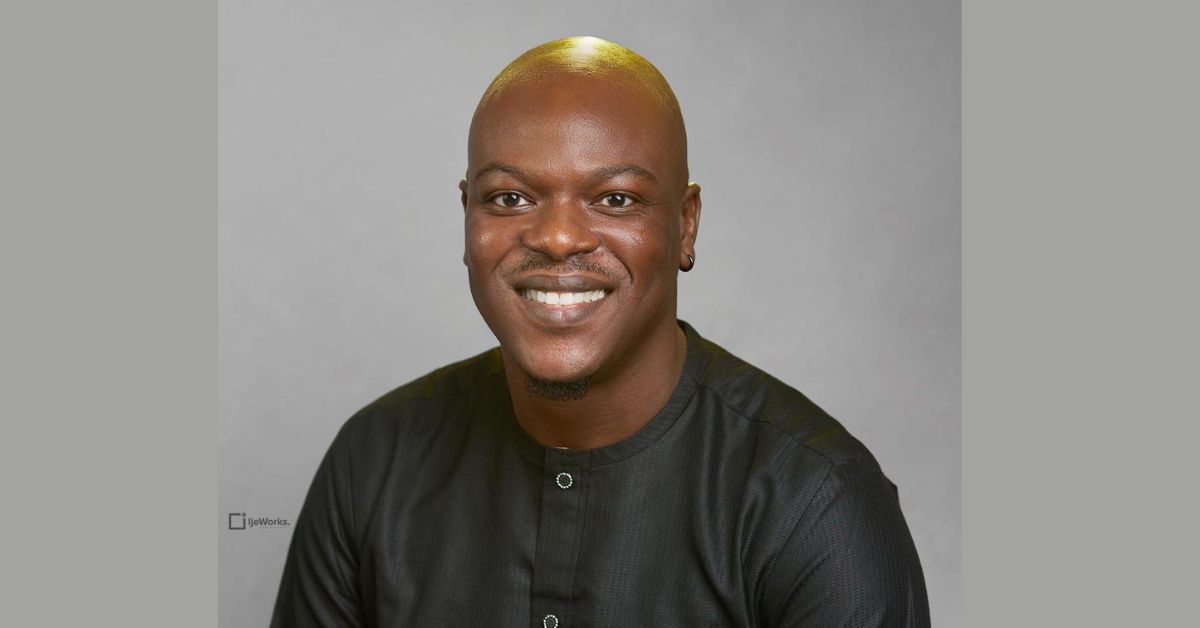

However, payment has been slow, according to Gbenga Adebayo, president of the Association of Licenced Telecommunication Operators of Nigeria (ALTON).

“If you look at the number, it is not going down,” Adebayo told TechCabal. “The ₦200 billion, which consists of the principal sum and the interest is likely to rise if the payment continues to drag.”

“We believe that our friends in the banks can do better than what they are doing.”

The snail’s pace of repayment is one way the banks are sticking it to telcos, one person claimed.

“There was no agreement between the banks and telcos about sharing USSD fees from the beginning. The banks only discovered the telcos were interested in the fees when they started to threaten to cut the service,” said a bank CEO who asked not to be named so he could speak freely.

“There is no such thing as an obligation due from banks to telcos,” said Herbert Wigwe, the late CEO of Access Holdings during a 2021 investor call.

Other bank executives question how telcos arrived at the debt figure, insisting there’s little transparency around the billing process.

In 2023, GTCO’s Segun Agbaje argued the responsibility for collection should fall to telcos since the entire ₦6.98 fee per transaction goes to them.

While regulators have forced banks to collect and remit the fees to telcos, the banks appear to be pushing back by slowing the pace of payments.

USSD was originally built by telecom companies to provide airtime and subscriptions to customers, but it quickly became obvious that banking was a strong use case. Unlike mobile banking, customers don’t need the internet or smartphones to use USSD.

The great push to USSD began, with banks like GTCO launching splashy marketing campaigns for their *737 shortcode in 2016. Other big banks followed suit. In 2021, Nigerians sent ₦5.1 trillion via USSD. That figure declined to ₦4.4 trillion by 2022

Although USSD remains the country’s fifth most used payment channel, it has the lowest spend-per-transfer (₦10,000) while the industry average for other channels (mobile app, online transfer) is ₦70,000, per National Bureau of Statistics data.

Ultimately, the telcos argue that USSD is an important channel for banking and that banks should collect and remit the applicable fees. However, given that the banks do not make any money from USSD and the payment values are relatively small compared to mobile banking, they’re incentivised to deprioritise it.

“If you want financial inclusion, then you need to bring down the cost of data. And when you bring down the cost of data, you start to eradicate USSD,” Agbaje argued in 2023.

With more security concerns as the industry fights fraud, USSD is no longer a priority for Nigerian banks and it may further slow the pace of payments towards the debt.

“It (the debt) won’t get resolved so the telcos need to let it go,” said a bank expert who chose to remain anonymous. It is a position many bank executives hold.