On a Tuesday morning in December 2025, I left my house in a rush to travel from Agbara in Ogun State to Surulere, Lagos. Somewhere between locking my home door and boarding a bus, I forgot the one thing I should never forget: my white cane.

To most people, a white cane is just a stick. To a blind person, it is sight. It tells me when the ground slopes, where a gutter is, how close a body is, and whether it is safe to keep moving. Realising I had left it behind sent a chill through me. I felt exposed. By the time the bus pulled away, my thoughts were fixed on a single question: how would I navigate my destination without my eyes?

Two months earlier, I had written about EyeGuide, a navigation app designed to help blind people move independently in Nigeria. At the time, it only worked on iPhones, relying on Apple’s LiDAR technology. But its developer, Charles Ayere, had said he was working on a way to bring the app to Android, where most blind Nigerians actually are, due to Android’s affordability and the low penetration of iPhones in Nigeria, where over 80% of smartphones run Android. Sitting on the bus that morning, with hope in my heart and fresh memories of how disorienting it feels to move without a cane, I sent him a message asking if there had been any progress.

His reply came almost immediately. EyeGuide was now available on Android, and he was testing it with his blind friend ahead of a wider release. That was how I ended up trying the app on a day I could not afford to take a wrong step.

Putting EyeGuide to the test

Anyone who lives in, or has even heard of, Lagos might wonder why a blind person would dare move around the city alone. But independence is not optional for us. If we waited for perfect conditions, we would never leave our homes. Life still has to happen, even in a city defined by beautiful chaos.

While still on the bus, I sent Ayere my email address. About 30 minutes later, he sent me a download link for the Android app. By then, I had less than ten minutes before getting down at Mile 2, home to one of West Africa’s largest food markets. There was no time to overthink it.

The app installed quickly, and setup was straightforward. After tapping “Get started,” I was not asked for any personal details. Before I could begin, a legal disclaimer appeared on the screen: “EyeGuide provides navigational assistance using on-device sensors. Always remain aware of your surroundings and use caution.” I paused. Trusting a navigation app as a blind person is not the same as testing a new music app. Mistakes here can mean injury or, worse still, death.

With that in mind, I tapped “Continue,” positioned my phone, and started navigating.

How EyeGuide’s Navigation works in practice

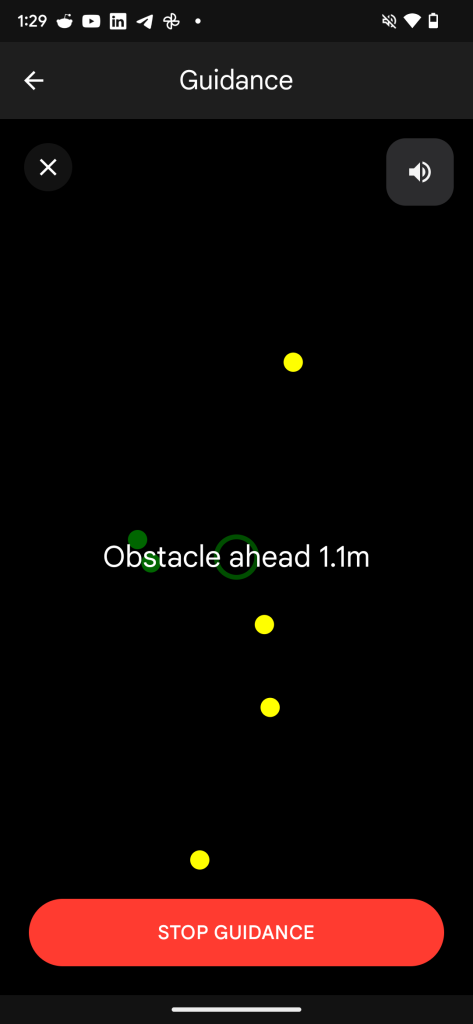

EyeGuide has four core functions, the first and most crucial being navigation. The Android version, instead of using Lidar, uses the device’s AR toolkit (Augmented Reality) and sensor fusion to understand the user’s environment, then measures how far each object is to the user by using onboard sensors such as the gyroscope and magnetometer to track movement, and then translates all these to the user through haptics(vibration) and audio feedback. It continuously scans the surroundings in real time, alerting users to obstacles and even the presence of nearby people.

Coming down from the bus at Mile 2, I activated the navigation feature. Holding the phone in front of me and plugging in my earpiece, I stepped onto the walkway and began moving. At first, it felt awkward. I am used to tapping my white cane along the path to guide me to a bus or finding someone who can help me flag a ride. Still, I kept walking, listening to the app’s built-in text-to-speech guide.

The first challenge was the constant beeping and vibrations. With so many people on the walkway, the app kept alerting me to every presence. At the same time, I was walking close to the edge of the path, and it repeatedly warned me about that too. Ayere had said the alerts are adjustable, and I later experimented with the sensitivity to make them less overwhelming.

I eventually found a bus, and my journey continued to Doyin, a busy transit hub along the Lagos–Badagry Expressway. There, the app revealed a limitation common to blind people navigating Lagos: crossing roads safely. Drivers here behave as if on a Formula One track, and even sighted pedestrians have to be careful. Drivers rarely understand that raising a white cane signals a blind person wants to cross. Accessible Pedestrian Signal which are standard safety tools for the blind elsewhere, are almost nonexistent in Nigeria. Standing at the roadside in Doyin, the app could not tell me when it was safe to cross. I had to wait 13 minutes for someone to assist me before I could proceed.

Once at my destination’s gate, I tapped the navigation feature again to reach my office. This time, moving through a quieter environment, following the cues was straightforward. I had already called a colleague to meet me because, while the app accurately identifies obstacles, it cannot yet guide a blind user to the precise entrance of a building.

I mentioned this to Ayere, and he said, “Implementing a turn-by-turn navigation system comparable to Google Maps is feasible, though it faces infrastructure constraints. Because existing map data for Africa often lacks the necessary precision, the system would require a crowdsourced data model to ensure accurate geocoding and address verification.”

For a blind person, getting to a destination is one challenge; locating the exact building is another. I once tried using Google Maps to find a building. It identified the street and number but offered no guidance on how to enter. If Ayere can solve this, it would be a game-changer for blind users.

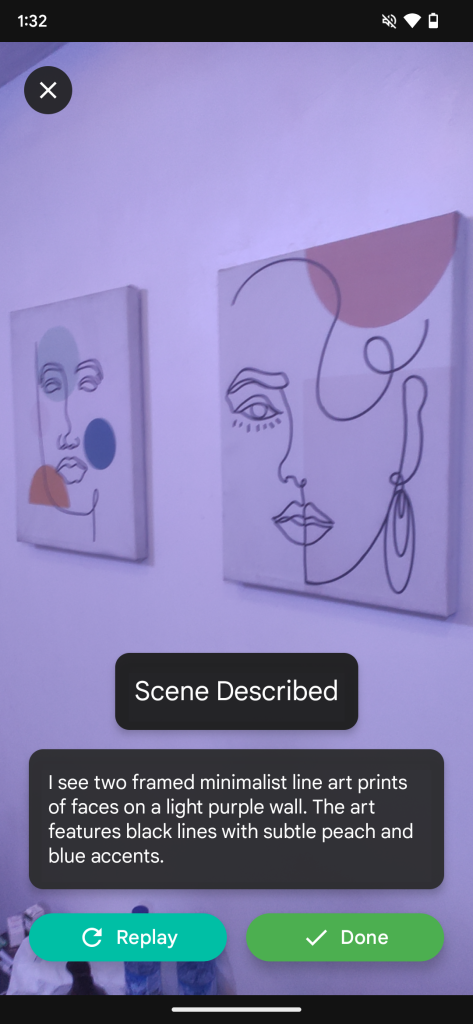

Scene description

Understanding your surroundings is crucial for everyone, but for a blind person, it can mean the difference between confidence and hesitation. After testing navigation, I turned to EyeGuide’s scene description feature.

Ayere explained that the feature uses the phone’s camera and on-device AI to identify objects and describe the environment aloud. It can recognise furniture, obstacles, doors, and even people, narrating the space so users can “see” it through sound. The goal, he said, is to give blind users context beyond immediate obstacles to help them understand the bigger picture of where they are.

To use the feature, you hold the phone at eye level, camera facing the scene you want described, then tap to start. I first tested it in my office. I asked a colleague to describe the room, then asked the app to do the same. It accurately described the interior, noting tables arranged with chairs beside them and a clear space down the middle, which it called a “walk path.” It sounded impressive, and I tried it again in another part of the building. The description was accurate once more.

Later, after leaving the office, a driver dropped me somewhere unfamiliar. I activated the feature, and it correctly told me there were vehicles parked in front of me. Turning the phone the other way, it warned of an open space, likely a hole or drain. For a second, that was terrifying. I wished the app could tell me how deep the drain was. With my white cane, I would have been able to measure the depth and width safely. A slight misstep back could have been disastrous. Luckily, someone appeared to guide me across the road and to a bus I could take home. I later learned from that person that the driver had not reached the bus stop due to traffic. I wish I had been informed before being dropped off.

The scene description feature is powerful, but it has limitations. It cannot yet provide full details of immediate obstacles like depth or texture, and it relies on constant internet connectivity for optimal performance. Ayere also warned that the AI might misidentify objects, so users should always confirm what they hear.

Smart reader

The Smart Reader function is one of EyeGuide’s most significant features. It has the potential to make a real difference for blind users. This feature can scan documents, books, and product labels and read them aloud. That means reading the label on a soft drink or a packaged product no longer requires a sighted guide.

To use the feature, hold the phone parallel to the document, place it on a flat surface, and keep it about 30 centimetres away to scan properly. I tested it on the label of a popular soft drink in Nigeria, and it accurately identified the product. I tried a variety of packaged items, and the app reliably told me what each one was.

Next, I tested the book-reading function, which relies on Optical Character Recognition (OCR) to read printed or handwritten documents aloud. With printed text, the app performed well. Handwriting, however, proved more challenging. Out of five handwritten samples I scanned, it read only two almost accurately. Ayere confirmed that the feature works best with printed text and that handwriting recognition is still a work in progress.

Lighting also matters. Bright, even light improves accuracy, while shadows or dim settings can reduce it. Despite its limitations, the Smart Reader could be transformative for blind students who receive handwritten notes or study materials. If Ayere can refine handwriting recognition, this feature would significantly reduce dependence on sighted assistance in classrooms and beyond.

Identifying currency and colours

The currency detection feature is a game-changer. While fintech platforms have made it easier for blind people to navigate without cash, Nigeria’s cashless market is still growing. Conductors and petty traders often still direct you to a point-of-sale POS terminal rather than accepting mobile payments. In this context, being able to identify cash independently is invaluable.

On that same Tuesday in December 2025, as I was heading home from the office, I used the feature to check how much money I had left, ₦3,00 ($2.11) in total, and to verify the change the conductor gave me after I handed over ₦1,000 ($0.70) for a ₦600 ($0.42) fare. Everything was accurate. Later, while writing this article, I used it again to identify the money I paid for fruits.

The colour identification feature works in a similar way. Hold the phone up to an object, and EyeGuide announces its colour aloud. It can identify a wide range of colours, though accuracy depends heavily on lighting conditions. Very dark or overly bright environments can affect the results. During testing, it correctly identified many colours, while a few were approximated to a close match. Still, for everyday tasks such as matching clothes, checking product labels, or organising items, it provides helpful context that would otherwise be inaccessible.

A tool built from care

EyeGuide did not start as a business idea. It began with a friendship. Ayere says the motivation came from watching a close friend struggle to navigate her university campus independently. Lecture halls, hostels, and roads were not designed with blind students in mind, and moving around the school often required help. That experience stayed with him.

EyeGuide, he says, is his response to that gap. Accessibility should not be a privilege. That is why the app has remained free since launch and will stay that way. Ayere has no plans to monetise the core app for profit, believing that tools designed to support independent living should be as available as water.

The Android release, however, is only one step in a larger plan. Ayere is currently developing EyeGuide-compatible wearables aimed at delivering a hands-free navigation experience, allowing users to receive guidance without constantly holding their phones. He says the wearable will be monetised just enough to sustain production and keep it affordable.

For many Nigerians with visual impairment, that future cannot come soon enough.