Across Africa, the increasing adoption of social media has over the years inspired the rise of social commerce—a type of online selling where transactions take place via social platforms (such as Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and WhatsApp) and largely involves direct business-to-consumer interaction.

Many African entrepreneurs have embraced this brand of e-commerce, which significantly differs from online marketplaces like Jumia and Konga or storefronts provided by fintech companies. In fact, Facebook and Instagram are used by Africans for online shopping more than e-commerce marketplaces, according to a 2019 GeoPoll survey, and social commerce accounts for the majority of e-commerce activity in Africa, per a joint report from GSMA and UNECA.

It’s easy to see why this is the case. Selling and buying via social media doesn’t require digital expertise and is thus more accessible to less tech-savvy vendors and consumers. For SMEs without access to loans or the capacity to set up stores, social commerce provides an avenue for them to grow their businesses and increase sales.

But most of the processes through which these sales happen—from discovery to order placements and payments as well as managing orders, customers, and inventory and deliveries on the seller side—are crude and inefficient. Silas Adedoyin and Segun Oladiran have teamed up to address some of these bottlenecks through Catlog, their platform which launched in private beta last November.

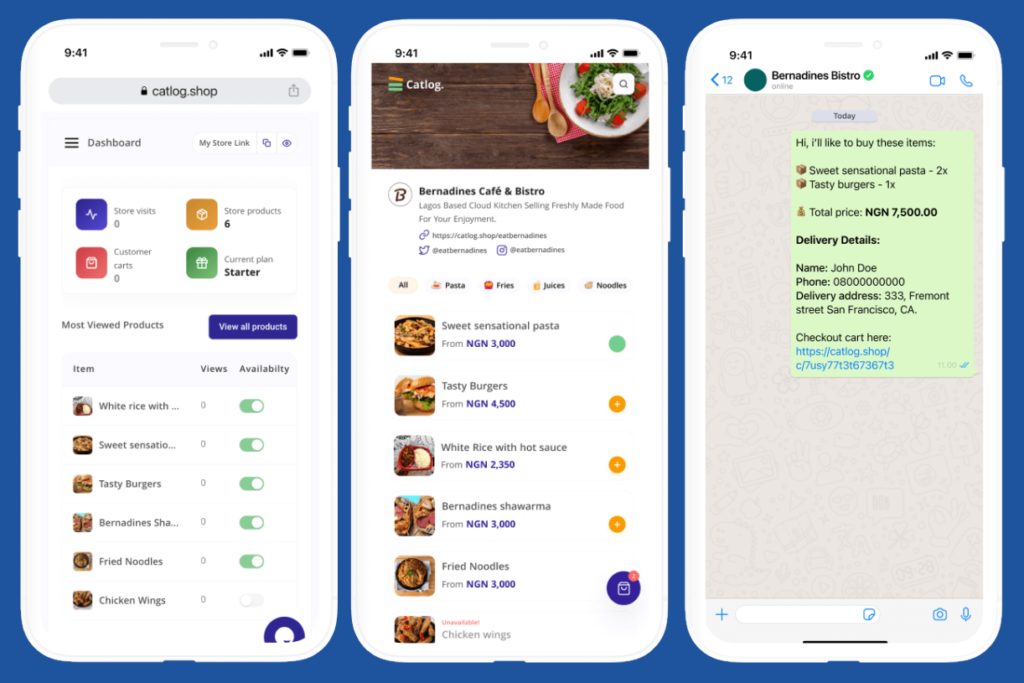

The Lagos-based startup offers vendors a simple way to create an online store on its platform, add their products, and create a custom link they can share on social media. Potential customers get to click on the store link and select the items they want to purchase. After this, interested buyers click on a button to reach out to the vendor, who automatically receives the order on WhatsApp. At this stage, a chat is initiated during which both parties finalise the details of the purchase.

Catlog started as a side project of Oladiran and Adedoyin, whose experience as a software engineer spans five years across full-time and contract roles in 5 companies. This includes Nigerian open banking startup Mono, where he led the web experience efforts but left in February to focus on Catlog full-time.

It’s not the first time he will try his hands at founding a startup. In 2018, 18-year-old Adedoyin dropped out of the Federal University of Technology Minna to focus on a social learning startup, Easyasitis, which he was building at the time.

“I was a first-class student studying mechanical engineering,” he recalls. “In a class of 150+ students, there were only 2 of us. I later relocated to Lagos in late 2019 with only ₦20,000 in my bank account. The rest is history.”

Easyasitis was a social networking platform, similar to Facebook, that helped members learn from one another. At its peak, the platform had about 5,000 users before it was shut down.

Later on in his career, Adedoyin experienced the hassle of social commerce when trying to buy a pair of sneakers through social media. Then the idea to set up a solution struck him, in an epiphany moment.

“Say I want to buy new sneakers. First, I have to check Twitter with keywords to find sellers. After this, I reach out to find out the brands and sizes available. This interaction usually involves a lot of back and forth, sharing of images and I might end up ghosting sellers, either because they don’t have what I like or their pricing doesn’t work for me,” he explains. “The whole process is a chore.”

Many companies have solutions aiming to address these issues. Most take the Shopify approach, which involves enabling vendors, who would normally sell via social media, to set up an online store to sell their products with orders taken and payments made on the website. But that isn’t markedly different from selling via Jumia and leaves a lot of informal sellers and buyers uncaptured. This is why Catlog has taken a different approach.

“Social commerce is called that for a reason. It has to be social,” Adedoyin says. “If people won’t buy from Jumia, they won’t do that from some random sellers’ website. It’s simply not fun filling out a long form just to place an order. So from the start, our approach to solving this problem has been different – we’re building around the platforms sellers use already instead of trying to take them out to a totally different world.”

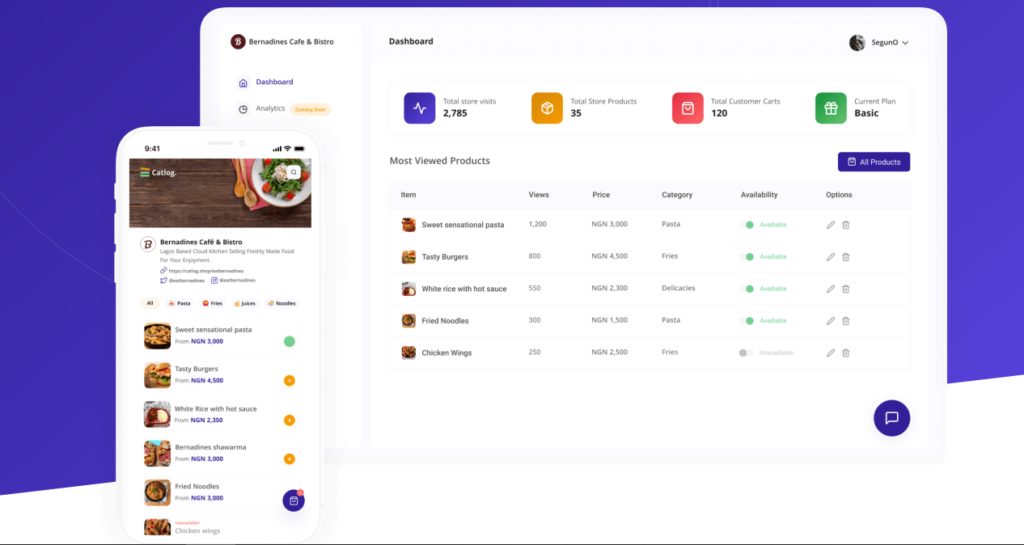

Catlog currently has hundreds of Nigerian sellers on its platform and primarily makes money by charging a monthly subscription fee of ₦900, with plans to roll out another plan in the coming months that “gives sellers more power and we get to charge more money,” according to the company.

The store can’t process payments for now, which, according to Adedoyin, is because most customers are uncomfortable paying online without speaking to anyone.

“Eventually, we plan to add a feature that helps sellers automatically generate invoices and collect payments, including a buy now pay later (BNPL) option,” he says. “We also plan to roll out escrow for the invoices, to solve the hassle of pay-before-delivery.”

Catlog recently launched a feature that allows sellers automatically add orders they receive on WhatsApp to their dashboard, thereby helping them keep track of all the orders received so nothing gets missing when it’s time to deliver.

“Previously sellers would have to manually write out orders and delivery details, and still, some orders get missed,” Adedoyin explains. “The feature also allows them to see analytics of how well their business is doing, manage details of buyers, and also automatically notify customers when changes are made to orders.”

Some other features currently on the Catlog roadmap include a chatbot that helps sellers respond to customers and take orders in their absence, a simplified way for buyers to find multiple sellers in specified areas and compare prices, credit facilities for sellers, and an easy way for sellers to find delivery riders.

In Africa, Catlog has a big market opportunity and plans to expand to more countries in the immediate term. The continent is one of the fastest-growing e-commerce markets globally with the number of online shoppers increasing by an average of 18% per year between 2014 and 2018, compared to the global average of 12%, per UNCTAD data.

Induced by the Covid-19 pandemic, even more people currently buy online. Most retail sales still take place through offline, informal channels, however, meaning there’s a huge market still to be tapped.

If you enjoyed reading this article, please share it in your WhatsApp groups and Telegram channels.