The BackEnd explores the product development process in African tech. We take you into the minds of those who conceived, designed and built the product; highlighting product uniqueness, user behaviour assumptions and challenges during the product cycle.

—

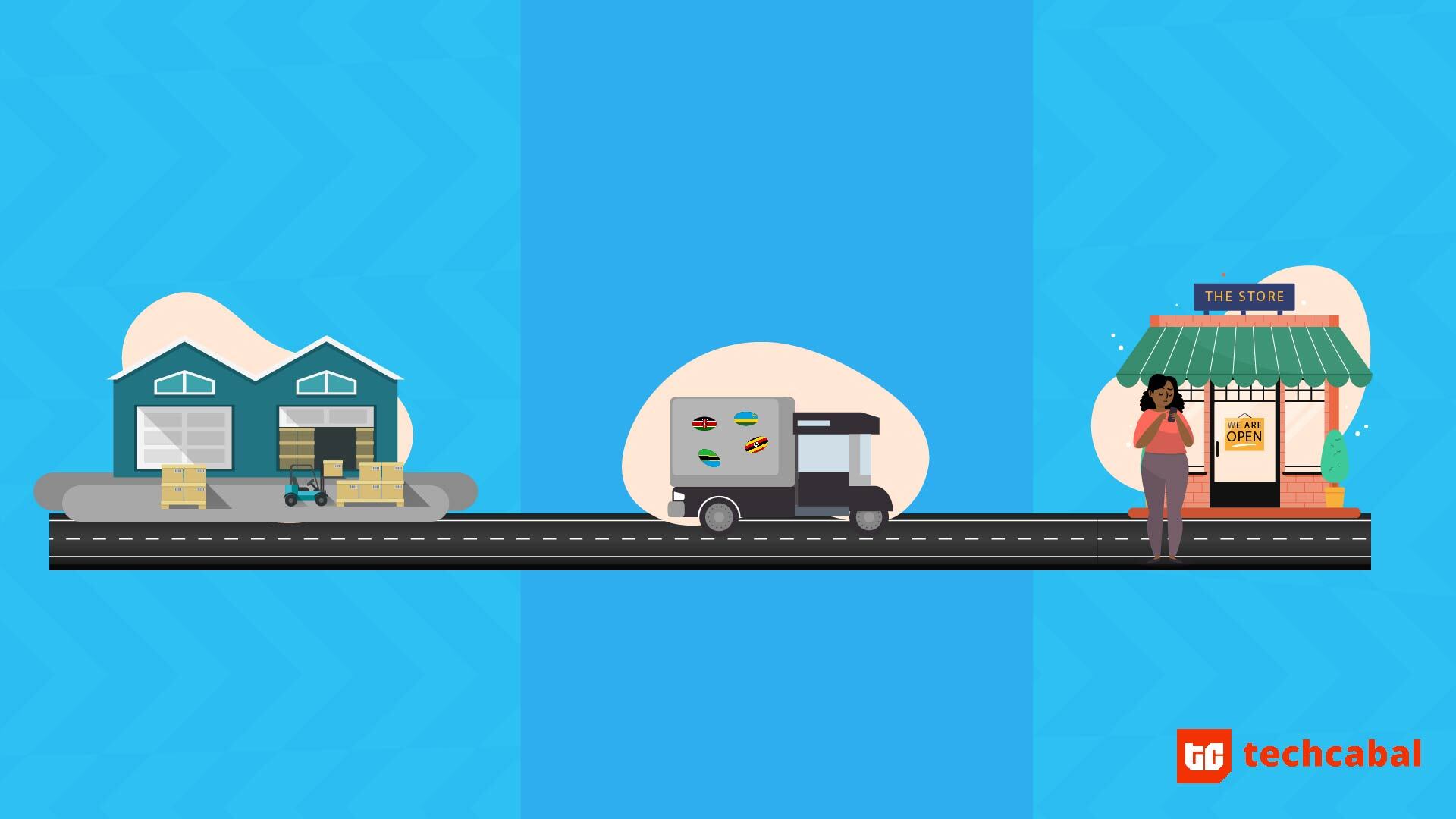

A trader in a corner shop in Nakuru, Kenya who sells groceries has a hard time getting regular supplies. Distributors don’t bring goods to her because she typically orders small quantities.

When retailers like her need to restock, they may have to shutter their shops, hire a taxi and journey to the distributors’ depots. These lost hours translate to lost income.

Daniel Yu stumbled on this problem indirectly. While living in Egypt in 2012, he got the idea to build a digital inventory management system connecting rural health centers to sources of medical supplies.

The project, Reliefwatch, worked for about a year and a half with some success in five countries in Africa and Central America. But the customers were multinational health centres owned by NGOs; there was no clear path to a for-profit business.

Realising there was more potential in fast-moving consumer goods, Yu secured an opportunity in Kenya. In 2015, he deployed Reliefwatch’s system to begin delivering chewing gum.

That pivot became Sokowatch, a same-day delivery company that supplies over 16,000 informal retail shops with basic goods from milk to foodstuff.

Tuk tuks as mobile warehouses

An American software developer with Silicon Valley work experience, Yu designed Sokowatch to be a platform where retailers find distributors and seamless exchanges ensue.

It was based on the ‘hire the community to serve the community’ thesis that online marketplace platforms are built on.

But finding distributors was not the problem in Kenya; distributors simply had no incentive to meet small-scale traders halfway. So Sokowatch began investing in logistics and warehousing.

The company stocks the most requested goods in its warehouses. They deliver to retailers through agents who operate tuk tuks (tricycles).

The tuk tuks embody the blend of warehousing and logistics, acting as mobile depots available to retailers on-demand. Kago Kagichiri, Sokowatch’s Global Head of Innovation, describes the tuk tuks as the core feature of the company’s business model.

Unlike motorcycles, tuk tuks have more space to contain goods. In East Africa, they are mostly used for cargo so it is natural to adopt them as mobile warehouses. Unlike vans and pickups, they are not as expensive to procure and maintain. They also take-up less space when parked on street corners.

Retailers not accustomed to the internet can place orders by sending toll-free text messages. They receive a call confirming their order, and a tuk tuk delivers to them. More established customers use Sokowatch’s app to browse and order for themselves.

Where a tuk tuk is out of stock, a dispatch rider from the main warehouse restocks the tuk tuk from which the order goes to the retailer.

With at least three years of data on retailers’ requests, Sokowatch has developed a ‘smart call list’ with which retailers’ needs can be predicted based on their past calls.

This data enables Sokowatch to reach out to customers ahead of time to check in on their stock and schedule their next delivery.

User interaction: Who uses Sokowatch?

Sokowatch is present in 9 cities spread across four African countries. They have at least one warehouse in each of these cities – they have two in Nairobi, the epicentre of their operations.

With a fleet of about 200 tuk tuks (100 plus in Kenya alone), the company sets itself apart from distributors, but it has a structure for collaborating with them.

A major reason why distributors find it difficult to go to kiosk owners is because they often have no place to deposit bulk goods for pickup. Sokowatch is able to deploy its warehouses as train stations of sorts for these suppliers.

Leveraging its wealth of data, the company can better advise suppliers on the performance of their goods in specific areas, Kagichiri says.

They have engaged some suppliers in income-sharing agreements based on joint business plans; to jointly supply goods in areas where they have common interests.

Whether going solo or in collaboration, Sokowatch’s target market remains shops that make between $25 and $100 in daily revenue.

The nature of these businesses is such that having stock is key to making ends meet. The low-margins nature of the business creates the need for each retailer to have steady stock to sell.

That is not always possible due to secondary financial needs that diverts cash away from the business. To solve this, Sokowatch has integrated a lending scheme which traders can tap to balance work and life.

Credit-as-a-service and other VAS

The credit is working capital. Shop owners can order goods on credit during the day and make enough to repay by close of business or at later dates.

Kagichiri gives an alternative reason for this kind of credit: corner shops themselves are microcredit providers in the way they sell to their neighbourhood people on credit. By this logic, Sokowatch is a lender of last resort enabling liquidity in the system.

The credit can also be for specific acquisitions. An example is their smartphone financing loan, aimed at helping traders buy smartphones and repay conveniently.

Offering credit in-kind by tying it to actual consumables has real advantages. It forestalls the microcredit craze in Kenya where some people borrow cash from up to four lenders only to feed passions like online betting, or using a loan from one lender to pay another.

“It’s heavily de-risked versus any other type of microlending that other players might be doing,” Yu says.

Building for something bigger

Sokowatch is not alone in this ecommerce-logistics space in East Africa.

In Kenya, Twiga foods, a B2B platform for connecting farmers to urban retailers, has a robust basket of goods with which to compete. Sendy’s fleet of vans and pickups can rival tuk tuks on reliability, and they have FMCGs like Unilever among their clients.

Providing value added services like credit is therefore necessary for Sokowatch’s market differentiation and expansion plans.

Kagichiri says “there’s probably space for three of four Sokowatches within the market,” but believes his company’s advantage rests on the data they have garnered over time.

With location data on agents and retailers, they are regularly fine-tuning delivery times , he says, making sure supplies get to where they are requested as soon as possible.

COVID-19 opened an opportunity to offer e-vouchers with which individuals and households in need can buy goods from retailers. The e-vouchers run on SokoCash, the company’s e-wallet. That platform is being explored for other services like insurance.

“The idea is to get engineers to create proofs of concept from the ideas we are seeing. These could become services for our agents and retailers,” Kagichiri says.

At the moment, they put printed banner ads on the tuk tuks, but I ask Kagichiri why they have not used electronic boards instead knowing the kind of advertising business that could become.

He is intrigued by the prospect but sounding circumspect, he says: “You need to find a scalable way to do it with three or five clients before determining that it is a product.”