On a sunny Tuesday afternoon on October 13, 2020, Lagos State governor, Babajide Sanwo-Olu, came out to address protesters in front of his office at Alausa, Ikeja. The protesters had been hanging around the governor’s office for almost a week, clamouring for a disbandment of the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS)—a special police unit known to terrorise and extort young Nigerians.

A few minutes into the governor’s address, the protesters interrupted his by playing a note from the chorus of “FEM”, a hit song by Nigerian musician Davido. FEM roughly translates from Yoruba to “Shut up!” This was the protesters’ way of telling the governor “enough of the talk”. Frustrated by the protesters’ unwillingness to listen, the governor later joined in the protest in reluctant surrender. But what seemed like a win for the protesters was truncated exactly a week later.

On the evening of October 20, over 50 protesters were killed and many more injured as officers of the Nigerian army opened fire on demonstrators at the Lekki Peninsula toll gate, an incident that took the world by surprise.

Two days later, the Nigerian president, Muhammed Buhari made a nationwide broadcast to address the issue, making it clear that further protests would not be tolerated. He urged the protesters to “resist the temptation of being used by some subversive elements to cause chaos with the aim of truncating our nascent democracy”.

The president didn’t need to rely on any song to pass along the message that, this time, it was the turn of the protesters to shush. The two weeks’ protest had come to an end.

So what’s happened since then?

Twitter’s influence nipped

Social media platform, Twitter, was integral to the nationwide demonstrations.

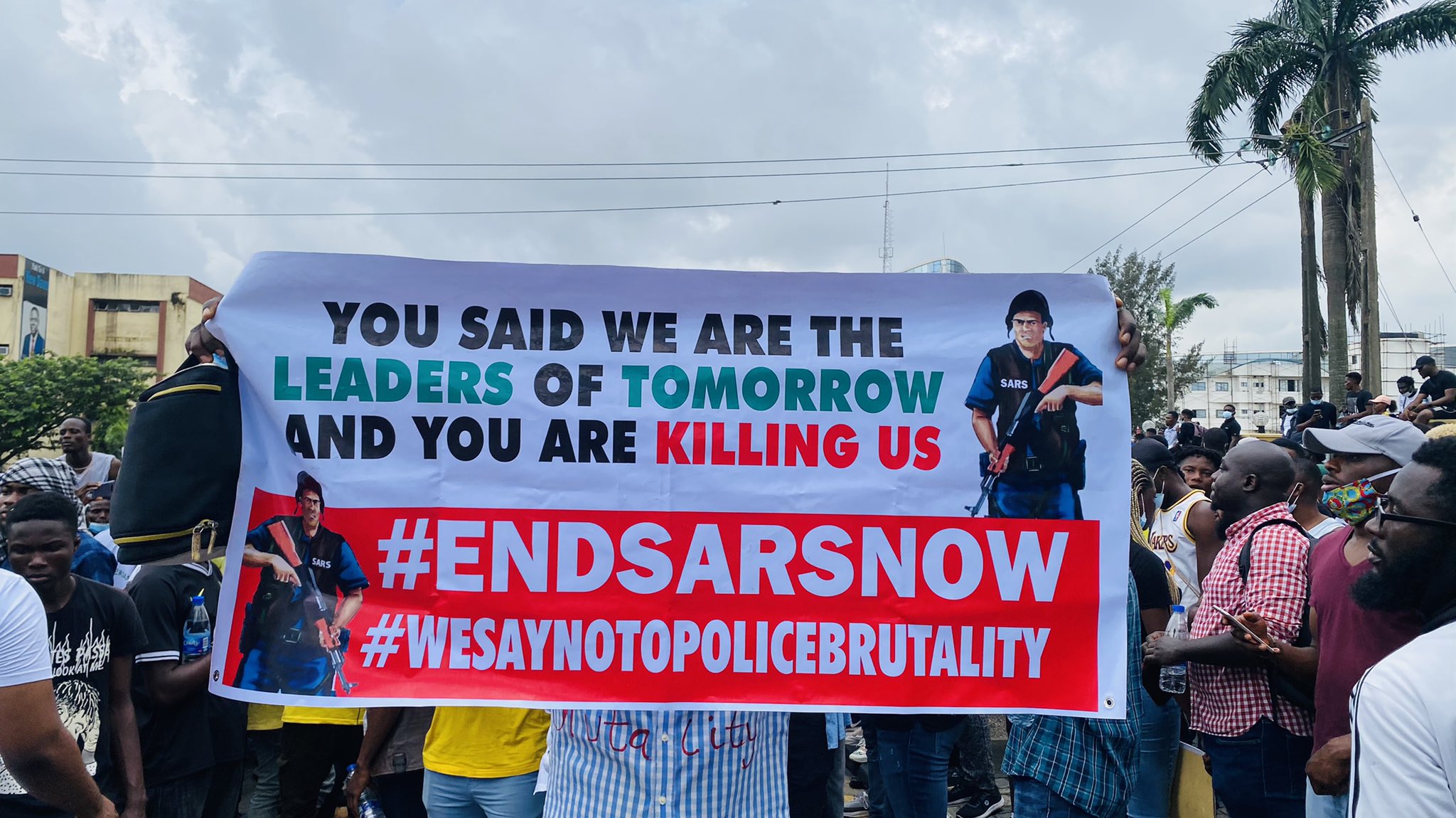

The #EndSARS protests had initially begun on October 4, when videos went viral on social media of youths protesting after a young man in Ughelli, Delta State was shot and killed by SARS officers. This was not an isolated incident. In the last three years, Amnesty International has recorded 82 cases of torture, abuse, and extrajudicial executions conducted by the rogue unit.

With that video, online interactions on Twitter added momentum to the protest. Every day, millions of Nigerians followed the hashtag #EndSARS to keep up with the latest happenings and mobilise one another. Traditional media couldn’t be trusted with accurate information as a number of media outlets cherry-picked what aspects of the protest to share.

The first week of the protest went by normally until October 14 when Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey got involved. He tweeted two links with the hashtag #EndSARS—one to an article explaining the history of police brutality in Nigeria’s tech community and the other to the official website of the Feminist Coalition (Femco), a group that supported the peaceful protests by ensuring the safety of Nigerians.

Dorsey took it a step further, soliciting Bitcoin donations “to help #EndSARS.” Two days later, Twitter created a special emoji—a tight-fist emoji painted in Nigeria’s national colours, green and white—to support the movement. With the help of Dorsey’s endorsement, Femco managed to raise $150,000 in Bitcoin donations after its bank account was deactivated by Nigerian authorities.

All these moves by Twitter drew praises from the protesters while the Nigerian government criticised the US tech giant for spreading misinformation and later blamed the platform for funding the EndSARS protests.

It wasn’t until seven months later that the Nigerian government found an opportunity to nip Twitter’s influence in the bud.

On June 4, 2021, the government announced a suspension of the microblogging platform, following Twitter’s decision to delete a tweet by Nigerian president Buhari, which it said breached the site’s rules. The next day, millions of Nigerians couldn’t access the site except via a Virtual Private Network (VPN).

Five months and counting, Twitter remains banned in Nigeria.

Seeking restitution

In the past year, victims of police brutality and the shooting at the toll gate have sought some form of restitution. Last December, over 2,500 petitions were received at the judicial panels set by 30 state governments to investigate the excesses of the Nigerian police. What happened to the petitions?

In August, Vice President Yemi Osinbajo said that all 28 states that established Judicial panels had concluded the hearings, except Lagos, which was to wrap up in October.

The Lagos State Judicial Panel of Inquiry, which started sitting on October 26, 2020, recently came to an end on October 18, 2021, with the panel awarding a total compensation of ₦410 million ($900,000) to 71 petitioners. In July, the Bayelsa and Abia judicial panels awarded ₦21 billion ($47 million) and ₦511 million ($1.1 million) to victims respectively. The Edo and Delta judicial panel also recommended compensation of ₦288 million and ₦102 million respectively.

Notably, in Taraba State, no compensation was awarded to any victim.

In light of this, considering that the total compensation of about ₦22 billion is 33% of the 2021 Police trust fund budget, it might be difficult to enforce this judgement.

Contrary to what most Nigerians think, obtaining a positive judgement in court or a judicial panel is only one leg of the two-pronged approach to winning a case.

Since the case is against the Nigerian Police, according to provisions of section 84 of the Sheriff and Civil Processes Act 1955, the consent of the federal or state attorney general is needed to for the judgement to be enforced, should the Nigerian police push back. This provision grants the attorney general some discretion to determine whether certain judgments of courts may be enforced against monies in custody or control of a public officer.

Hence, it’s one thing that the compensations are awarded, and another that they’re paid.

Disbanded but still active

On October 11, 2020 the Nigerian government disbanded SARS. The news was taken with a pinch as this was the fourth time in four years the government had made such an announcement.

The disbandment of SARS might have reduced the number of police brutality cases. However, it hasn’t entirely prevented harassment by the police force.

Last month, Victor*, a 26-year-old software engineer, and two of his friends were on their way home from a colleague’s birthday celebration at midnight in Benin City when they were stopped by five police officers.

“What started as a routine check turned into a heated-up conversation,” Victor told TechCabal.

The police officers got into the passenger’s seat and threatened to frame Victor and his friends if they didn’t bribe them. Considering that it was midnight, the trio gave in to their demands, settling the police officers with a sum of over ₦100,000.

Many of such cases have been shared by Nigerians on social media over the past year, it’s difficult to keep count of them all. In the second quarter of this year, nearly 300 Nigerians were reportedly killed by security personnel, including Customs, DSS, NSCDC, Police and the Military, per a report from SBM Intelligence. SARS may be gone but police abuse remains rampant in Nigeria.

“The EndSARS protests showed people that there is power in mobilising at the grassroots, but how it ended might have sent the wrong message: that we did our best but the government still got what they wanted,” Chinwe*, a lawyer said.

Michael Ajifowoke contributed to this article

*Names have been changed.

If you enjoyed reading this article, please share it in your WhatsApp groups and Telegram channels.