The BackEnd explores the product development process in African tech. We take you into the mind of those who conceived, designed and built the product; highlighting product uniqueness, user behaviour assumptions and challenges during the product cycle.

—

When Somto Ifezue, Joshua Chibueze and Odunayo Eweniyi sensed an opportunity to build an app to help Nigerians save money, they already had some experience with the tech startup hustle.

Writing code would not be the problem, neither was the challenge about merely designing an interactive website. They had a team of 6 ready to go.

But if it would be truly useful, the savings app had to connect with users at an emotional level, simulating a human-to-human guidance and counselling relationship. There had to be carrots and sticks.

To save is to defer gratification, to deny yourself of pleasures now for more rewards and an increased level of productivity in the future. This isn’t our default setting as humans.

Famous studies like the Marshmallow test have shown that we are hardwired from infancy to want pleasure now, as against waiting for some appointed time.

Yes, it becomes easier to rewire this tendency in adulthood. But if you live in Nigeria, you are probably not a great saver thanks to unfavorable macroeconomic factors – unemployment, high inflation – that affect your daily decisions. Nigeria has a way of making her residents live for the moment.

So how do you convince people that saving is not only necessary but possible? How do you digitally design carrots and sticks?

Positive and Negative motivation

By the end of 2019, about one million users had saved $80 million on Piggyvest. It’s a massive rise in adoption from their first year when they were at a little over $54,000 from 450 savers.

Most of this has been powered by Quick Save – the automated direct debit feature that takes money from a user’s bank account either daily, weekly, or monthly depending on the user’s setting. This is the direct digital upgrade on manually putting money into a wooden box.

The carrot is the daily interest Piggyvest pays on these savings. Users can observe this for themselves on the app, inspiring a visceral sense of achievement that isn’t available when saving in a commercial bank.

But the novelty of Piggyvest is that it has convinced users to accept potential punishment (a 5% breaking fee for withdrawing from Piggybank before a set time) in order to become better savers. It’s like voluntarily engaging a friend to teach you to cook; every time you taste the food while it’s cooking, he takes out a portion from your raw ingredients.

It turns out humans are not averse to negative motivation if reward for an action is, on balance, better than the best alternative foregone. In the case of saving money, the alternative to being potentially punished with a 5% fee on an app like Piggyvest is potentially not saving anything at all.

If a user’s desired outcome is to save something, the risk of a penalty becomes worth bearing because at least they stand a chance of being better off.

Piggyvest has held firm to this insight on human behaviour, layering on other products to encourage targeted savings, saving in dollars and saving for emergencies.

But in expanding product offerings, how much control can you have over users’ financial choices?

The SafeLock dilemma

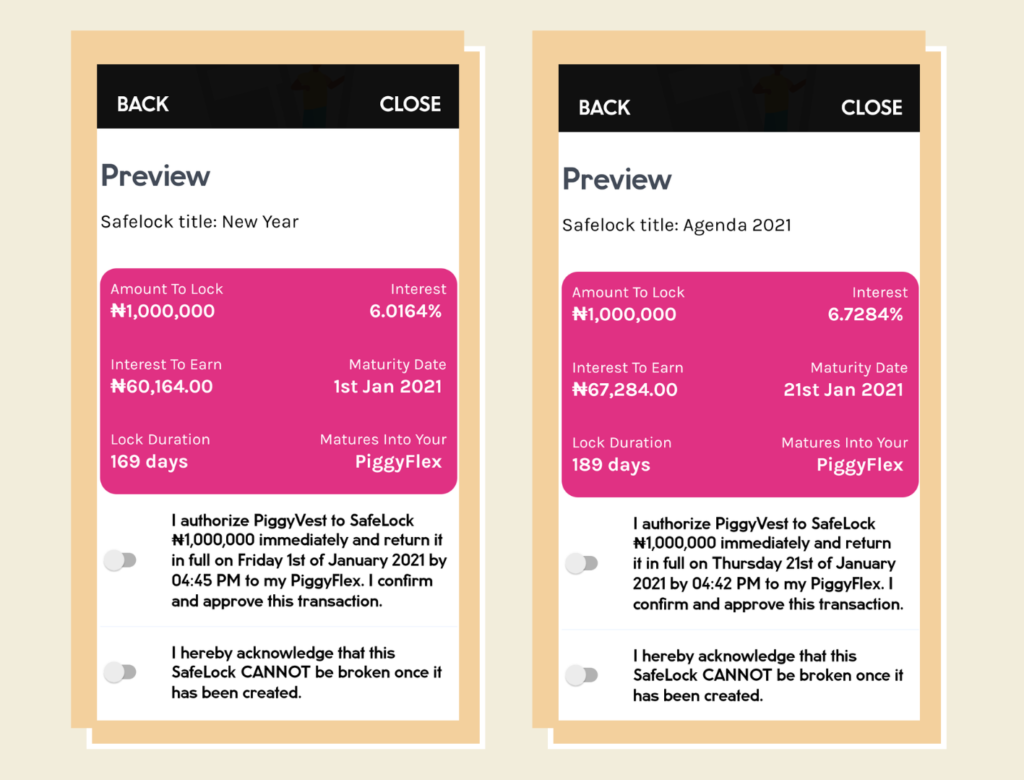

On SafeLock, users agree to be temporarily separated from their money for a period. Piggyvest pays the interest upfront once the money is locked. Users can withdraw this interest from their account immediately, or whenever they please.

What a SafeLock pays depends on the amount locked and the maturity date, as the real-life samples below show.

Introduced in March 2017, the idea for the product arose from user requests, Piggyvest’s founders say.

But it was modeled after treasury bill transactions, where a buyer is paid a fixed percentage of their capital depending on how long you permit the government to hold your money.

The average amount in a Piggyvest SafeLock is about ₦500,000 (~$1100), and is typically locked for between 4 and 6 months. Essentially, a SafeLock is a customised fixed deposit account.

Helping users lock money away is a useful service, but should it be impossible to break a SafeLock no matter the circumstance as the company insists?

“We try to make it as clear as possible when you are locking funds that this cannot be reversed,” Ifezue, the CEO, says.

When they initially took a lenient approach towards exceptions, defaults spread like rapid fire. The most common excuse was sickness. The same word-of-mouth channels that gave the app its customer base was becoming a medium for a potential virus.

These days, they stand their ground. “We prefer for people to warehouse their emergency funds in their Flex wallets. They can interact with that at any time,” Eweniyi, Piggyvest’s COO says.

To help users think through their decision, warning signs and multiple authentication requests pop up at various points during the transaction chain. An email is sent to the user’s email for every SafeLock request completed; the user has 24 hours to cancel the request if they please.

After scaling these fail safes, it would have been the wholly user’s choice to lock their money away. Having paid the interest up front, the company has a strong case for refusing to break the lock afterwards.

The company suffers no liability, provided it guarantees the safety of the locked funds for the duration. As you may have noticed, fintechs and banks have never been more attractive to hackers and cyber stalkers.

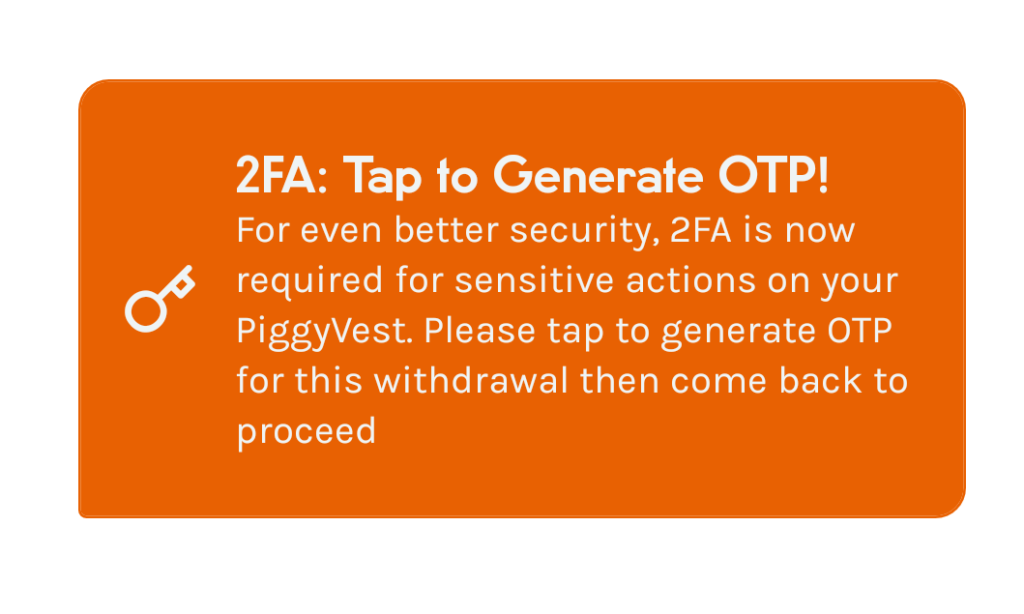

Two-factor authentication*

This week, Piggyvest introduced two-factor authentication as an extra layer of security. It is not clear when it was built but the rollout comes barely a week after an intrusion into a Cowrywise customer’s account.

Tabs for a one-time password (a six-digit pin that expires after ten minutes) and security questions have been added to complement the password requirement for major activities like withdrawals. Eweniyi explains the new security features:

“OTP has been enabled by default for every user, and following that, they have to set their security questions as well. At withdrawal, an answer to the security question and the password must be provided, while the flagging system runs a check on the account.”

The user sets a security question once; it will be required for all withdrawals on the app. When a user fails to answer the question for any transaction, the account is restricted for an identity check.

As to why the OTP is sent to an email address instead of by SMS, she explained further:

“We are using emails because of the instant deliverability, SMS is not always reliable… if a user can’t answer the question set, the account is restricted automatically and the user has to complete an identity check. Key account changes and sensitive data cannot be altered on your Piggyvest account without identity check and confirmation.”

In other words, even where an intruder may access a user’s email and SMS, they will be foiled when they fail the security question. Eweniyi said they are exploring a biometric option.

Multiple products, one mission

The average age of an active Piggyvest user is between 25 and 30. They don’t have a lot of active users in the 18 – 25 bracket. Ifezue estimates that 99.9% of their users are comfortable smartphone users.

Financial inclusion conversations are often framed around the need to go beyond this demographic towards older users who are less tech savvy. But he sees no need to rush, believing the proportion of Nigerians who own (and eventually would become comfortable with) smartphones will continue to increase with time.

Piggyvest’s disposition is that the pace of growth will continue to be defined by customer feedback, maintaining the word-of-mouth marketing model they have relied on over the past 45 months.

They don’t want to be a commercial bank, or sell airtime. Ifezue captures the product mission as building a platform for users to focus on paying themselves. After paying the landlord and budgeting for other bills, everyone should pay themselves at least 30% of their earnings, he says.

Self-love and financial control, at the touch of a button.

* This section on two-factor authentication is an update to our description in today’s edition of the TC daily newsletter