Sola Olubayo* got fed up and set out for Lagos without telling her mum.

After graduating from Ekiti State University (EKSU) with a degree in Computer Science, the best ‘tech’ job she found was at a bootstrapping shop that built WordPress sites. It paid ₦20,000 ($52), a fraction of a dollar above the national minimum wage at the time.

This was not why she spent days and nights migrating from a stint with React to learning Flutter. She had applied herself to become a software developer on the encouragement of her head of department who told her she was “smart enough to learn how to code.”

Olubayo is an active member of a tech community in Ekiti state where she was born. Through her work, young women in the state access grants to enroll for online courses on software development.

But moving to Lagos where she now works at an electronic payments company as a front-end engineer was a necessary career move. She left, despite having no family in her new destination.

An awakening

This storied exodus of young talents might soon change if recent actions by Ekiti state’s handlers are anything to go by.

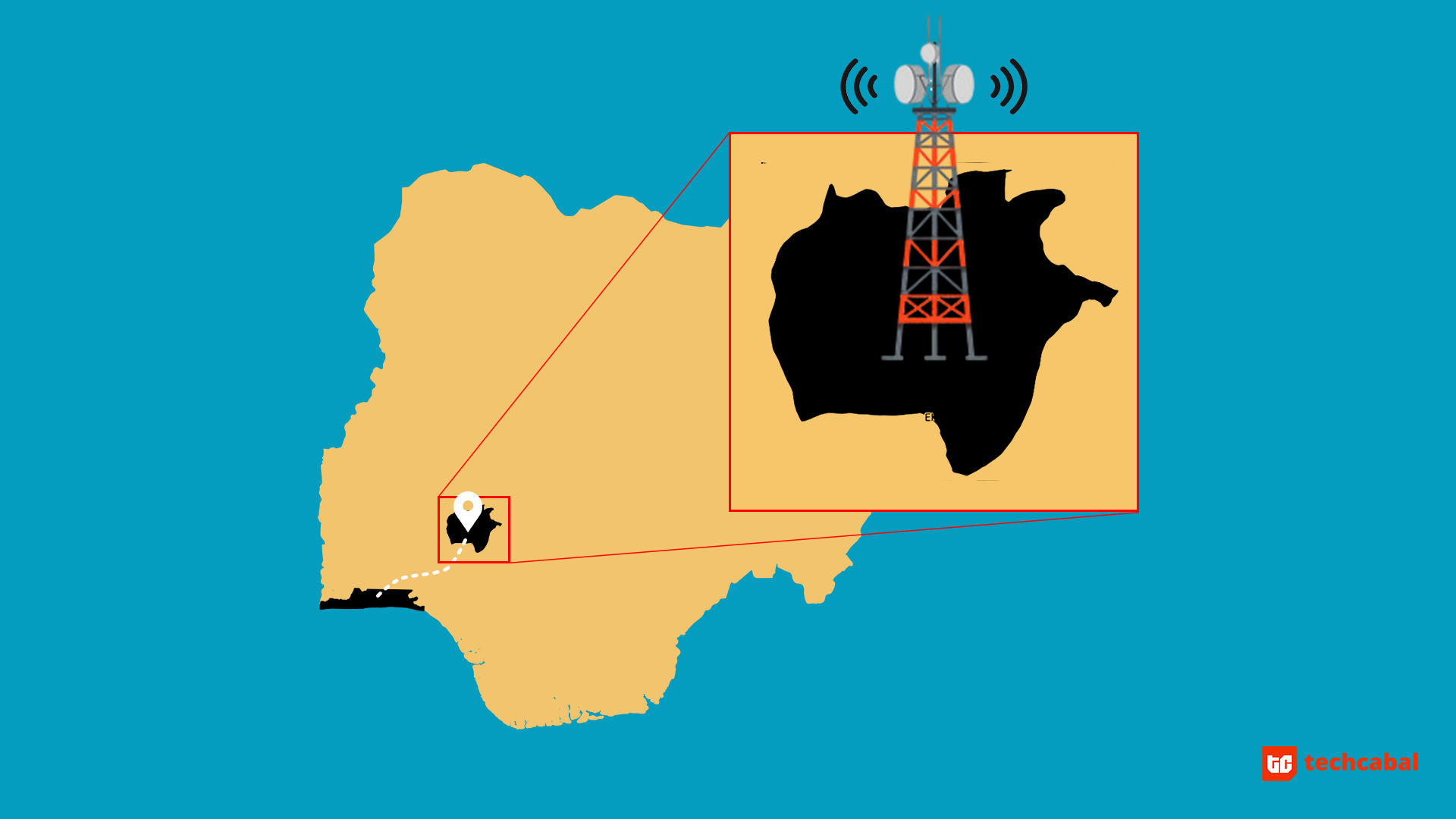

In May, the state’s governor Kayode Fayemi signed an Executive Order reducing Right of Way charges for laying broadband infrastructure from ₦4,500 ($12) to ₦145 (37 cents) per metre.

A week after the RoW fee reduction, the state signed an MoU with O’odua InfraCo to lay 606km of fibre. O’odua holds a federal government license to provide broadband infrastructure to five states in southwestern Nigeria.

Under the agreement, O’odua is exempt from the ₦145 RoW charge. Leveraging the state’s ‘Dig Once’ policy, O’odua has free access to create the state’s single pipeline for fibre optic infrastructure. But it will provide multiple ducts for other providers to access the pipeline, subject to a rental charge.

The reduced RoW charge appears to be bearing fruit in other ways. MTN, the mobile network operator with 43% (the largest) share of internet subscribers in Nigeria, has requested approval to lay 160km of fibre across the state, according to a reliable source close to the matter.

As of 2018, Nigeria had 38,000km of fibre optic capacity. It’s a far cry from the 120,000km the communications regulator estimates is needed to improve broadband coverage beyond the current levels at 40.14%. The national broadband plan aims for 70% penetration by 2025.

But 700km can be significant for a state with 16% broadband penetration. Reducing the RoW charge serves a plan to increase access in the state to cover 90% of the population, solving middle and last mile delivery challenges.

Increasing coverage is part of a broader mission: to establish a knowledge economy frontier, an alternative to Lagos for foreign investors seeking an African hub for tech innovation.

How do you build up a state, almost from scratch such that it becomes attractive to investors and job seekers whose first port of call is to head for Lagos or Abuja, Nigeria’s federal capital? There might be a success story to learn from.

A micro-model for enabling innovation

As Favour Chukwuedo prepared to move to Ekiti for his mandatory national service in 2018, he wanted to be connected to the kind of community of tech enthusiasts he was accustomed to as a Lagos-based developer.

Through a Facebook search, he got in touch with organisers of the Google Developer Group in his new home. Within weeks, he attended a hangout featuring a “handful” of people.

Chukwuedo took up a more active role in the group, helping to organise an offline event attended by over 600 developers in February 2019. Some participants travelled from neighbouring states, Ondo and Ogun. Google experts from Lagos and Abuja attended as speakers.

By the end of his service year, Chukwuedo challenged himself further. In partnership with TechQuest, a Lagos-based non-profit academy, he undertook a project to introduce 2,000 school-age children in low-income communities to STEM education. Basic digital literacy and coding classes were organised for students in senior secondary school.

His highlight reel includes fitting a room in the state’s major library with desktop computers and internet access to give it a modern facelift. Most of the renovation – lighting, painting – was paid for by volunteers who bought into the project’s long-term value.

“What I learnt from this was that people must be interested in the project,” Chukwuedo tells TechCabal. This interest, he says, ensures sustainability in the absence of the project’s architects.

Development projects at micro-levels of society like libraries or schools are reproducible. But that’s not the challenge facing Ekiti. On the contrary, the task at hand requires a massive resource investment that could take years to complete. So what’s the plan?

A “less chaotic” innovation city

Based on a model of public private partnerships, the rollout of fibre cables in Ekiti will begin in urban areas, particularly around the 1,600 hectares of land in the outskirts of Ado-Ekiti earmarked for an innovation city.

The state’s broadband infrastructure will be a complimentary blend of fixed and wireless connections. Urban areas will have fixed connections, while most rural areas will have wireless connections.

It is expected that an MOU will be signed within the next 90 days announcing the deal for building the city. After that, real estate developers will be invited to begin work on residential and commercial housing.

The city is a pitch to business process outsourcing companies, and the back office teams of companies like Microsoft, Systemspecs, IBM, and Interswitch. Necessary amenities of urban life – primary schools, departmental stores, gyms, playgrounds – will be available within the city.

In June, the state commissioned a consultant to begin designing plans for an agro-allied cargo airport. And the state is actively searching for a new partner to take over operations of Ikogosi Warm Springs, a resort that should be a tourist attraction if well maintained.

Away from Lagos, new settlers will be able to “recreate their lives in a community that is cleaner, safer, and less chaotic,” as one government official describes it.

Perhaps more importantly, the combination of available internet and innovative tech companies will provide a space for existing talent in Ekiti, preventing the usual pattern where skilled talent migrate from the state to Lagos or abroad for greener pastures.

Can this really rival Lagos?

The majority of Ekiti’s 3.2 million people live in rural areas. Ado-Ekiti, its capital and most modern city is 320km away from Yaba, the suburban Lagos town regarded as the village square of Nigeria’s tech community.

With lower entry costs for laying infrastructure, the state hopes to have fibre optic cables in every community, such that residents can find a connection point no farther than 5km from where they live.

For the infrastructure builders, it’s a foray into uncertainty with regards to immediate adoption. Will they have to charge high fees to make returns on their investment?

As of today, the average annual household income in Ekiti is $1,500, according to an estimate by a state official. That’s about five times lower than the average in Lagos. If a market of consumers doesn’t already exist, there are no guarantees that this whole outlay will produce a return on investment in the future.

But as one administration official explained, low internet penetration in Ekiti is a consequence of the absence of consumption, instead of non-affordability: “It’s like saying someone cannot afford a car, but you haven’t built a road that passes through his house.”

A gradual move away from Lagos may not be far fetched in the near future.

Sim Shagaya, founder of edtech startup uLesson, speaks fondly of his decision to have his developers working from Jos, a city in the north-central state of Plateau.

Powering the dream

Broadband infrastructure alone will not make Ekiti compete with Lagos. The internet is capable of spurring rapid innovation, but it was built on another historic innovation: electricity.

As an undergraduate at EKSU trying to become a software developer, Olubayo never had the pleasure of using electricity from a government grid.

“I spent the whole four years in darkness,” she says, attesting to unresolved dire conditions that are anything but conducive to neither academic excellence nor personal development.

The picture she paints is of a “very, very hard” journey for would-be tech innovators in the state, especially for people outside of the capital where events like Google-sponsored meetups occur.

There are indications that the state understands the size of the challenge, with one official noting that investments in power is a critical enabling factor for the Knowledge Economy project.

In addition to the cargo airport, other key components of the future innovation city include affordable residential housing, commercial real estate, roads, sewage and waste management systems, as well as security.

But removing the RoW charge is seen as a vital first seed that offsets a cost item for infrastructure companies. One industry estimate says RoW charges account for 70% of the costs in the sector.

When the fruit of this seed matures, benefits will include expansive e-government solutions, more efficient communication of extension services to rural farmers, and for broadening access to educational tools to children in rural communities.

With regular broadband access, the state plans to introduce coding classes for secondary school students from age 11.

None of this will be available before December 2021, the earliest date for visible signs of progress according to the state. There are also uncertainties as to the continuity of these aspirations beyond the term of the governor which ends in October 2022.

But a few moves, like a partnership with Ventures Platform to “strengthen youth innovation and entrepreneurship” and the RoW charge reduction, point to the state’s zeal to divert attention from Lagos’s long-standing hegemony on innovation in Nigeria.